Unless you were born sometime during World War II, you have never seen anything like this before from a computing system manufacturer. Not the rise of Sun Microsystems, EMC, and Oracle during the Dot Com Boom, who were transformative to the commercialization of the Internet. And if the current trends persist with the explosive interest in generative AI, even the touchstone of blue chip system manufacturing, the rise of the IBM System/360 mainframe in the middle 1960s, might pale by comparison to the next explosive wave of growth for Nvidia.

You can rest assured that we will eventually build the spreadsheets and inflation adjust them to see who built the computing platform of their time fastest and most pervasively. But today, all we want to do – all anyone wanted to do – is dice and slice the financial results for Nvidia’s second quarter of its fiscal 2024 year. So let’s get going.

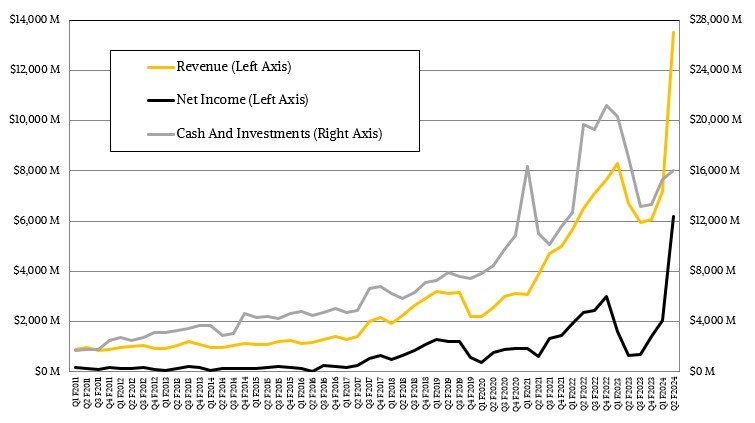

In the quarter ended in July, Nvidia’s revenues more than doubled year-on-year to $13.51 billion, its operating income rose by 13.6X to $6.8 billion, and its net income multiplied by a factor of 9.4X to $6.19 billion.

You want a wind speed indicator for interest in generative AI? That one ripped the spinner right off the weather station. . . .

If you look at the chart above, you can see the decline in gaming, the decline in the PC market, and the burning of cash to invest in the datacenter business that has caused revenues and profits to go nearly vertical. The only line that is steeper is the value of Nvidia’s stock price in after hours trading, which doesn’t do us any good because we don’t invest in companies that we write about. . . .

We are impressed by these numbers, but we are not at all surprised. How could you be if you have been watching the emergence of generative AI and doing the math on what the training and inference systems for the largest models cost? If the rumors suggested in the Financial Times are true, Nvidia can only make 500,000 “Hopper” H100 GPU accelerators this year (calendar 2023 is almost the same as Nvidia fiscal 2024, offset by one month) and that Nvidia was looking to ship 1.5 million to 2 million units in 2024. This stands to reason. If you want to train a GPT5-level model, you apparently need somewhere on the order of 20,000 to 25,000 H100 GPU accelerators, and that is somewhere around two dozen $1 billion machines that have on the order of 20 exaflops at FP16 floating point half precision without sparsity support.

So yeah, demand is going to be a lot greater than supply for a while, and that is why Nvidia currently has visibility into sales well into 2024. That’s because its capacity is on allocation, just like Intel was with Xeon SP CPUs back in 2019 and 2020 when it was at the top of the datacenter compute world. Oh, and by the way, by our calculations to reckon Intel’s revenues in its “real” datacenter business (including CPUs, networking, flash when it sold it, and so forth) was in the neighborhood of $9 billion four times in its history: Q3 and Q4 in 2019, Q1 in 2020, and Q4 in 2021.

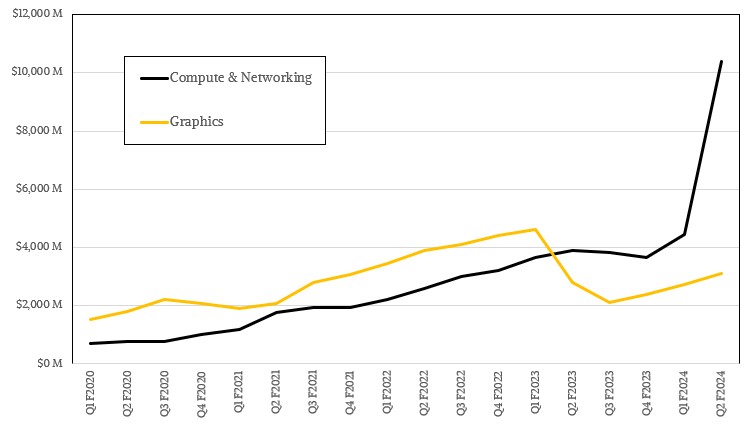

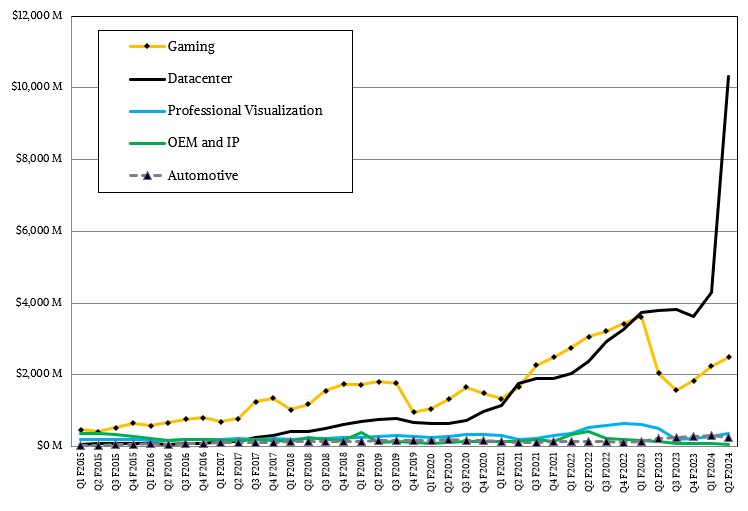

In Q2 of fiscal 2024, Nvidia’s Compute & Networking group generated $10.4 billion in sales, up by a factor of 2.7X, and its Datacenter division had sales of $10.32 billion, up 2.7X. The big cloud builders – think Google, Microsoft, and Amazon Web Services, given the restrictions of sales of full-blown GPU accelerators to China where Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu, which also operate clouds – accounted for more than 50 percent of datacenter sales in fiscal Q2, according to Colette Kress, chief financial officer for Nvidia, who spoke on a call with Wall Street analysts. The consumer Internet companies made up the next biggest piece of Q2 revenue, followed by enterprises and HPC customers.

So the big US clouds accounted for the lion’s share of around $5.5 billion in sales, which included not just GPUs, but HGX pre-assembled boards and InfiniBand and a smattering of Ethernet networking. Kress added that HGX cards represented a large portion of datacenter sales in the quarter, marking a shift away from using PCI-Express cards in enclosures and towards employing NVSwitch interconnects within the chassis.

If you take the other Nvidia divisions and separate them out and add them together, revenues were up by 9.9 percent to $3.18 billion. That’s another way of saying that the Nvidia datacenter business is now 3.2X bigger than the rest of Nvidia, and the datacenter business now accounts for 76.4 percent of the overall sales for the company.

Only a few years ago, when AI was on the rise, Nvidia shrugged off the loss of the big exascale systems for the HPC centers in the United States and Europe. At this point, chairman and co-founder Jensen Huang may have a soft spot in his heart for PCs and gamers, but the game is now almost entirely in the datacenter. It is great that there are hundreds of millions of CUDA-capable GPUs in the world for tens of millions of developers to play with, but that is not where the money is. And there is no reason to believe that Nvidia can’t ride the generative AI and recommender system waves for the next 18 months to 24 months.

We have said it before and we will say it again: The world is so crazy for generative AI that if you can do matrix math on a chip and it can run TensorFlow or PyTorch, you can sell it. And probably for quite a bit of money, in fact.

Hence, the launch of the L40S GPU accelerator, which we still need to analyze and which are guessing, without looking at any datasheets or estimated street pricing, will probably do 1/X the work of an H100 for 1/X of the price. Why would you sell it for less than that in this crazy generative AI world?

Given all of this, it is no surprise that Nvidia is projecting revenues for Q3 fiscal 2024 to be around $16 billion, plus or minus 2 percent. It won’t be long before Nvidia breaks $20 billion in a quarter and datacenter is 85 percent of revenues. Nvidia’s datacenter compute tail is not just wagging the gaming and professional graphics dog. It is a T-Rex in a buddy movie with the dog.

One last thing: Remember when we wrote The Case for IBM Buying Nvidia, Xilinx, and Mellanox way back in February 2017, which was a million years ago? Imagine, if you will, that Jensen Huang had been the chief executive officer of a revitalized and reinvigorated IBM for six years now. . . . IBM needed Nvidia a whole lot more than Nvidia needed IBM, but Nvidia could have used the reach and prestige of IBM a whole lot more than acquiring Arm.

Great article TPM, appreciate the amusements — mine and yours both, but don’t you think new *Sheriff* is more like it?

Come on, man. The Eagles? From Hotel California, the epic album of American excess and optimism? “Everybody loves you/ So don’t let them down.“

touché

“If you want to train a GPT5-level model, you apparently need somewhere on the order of 20,000 to 25,000 H100 GPU accelerators”…Perhaps if you buy in said quantity, they should ship with a 5% off coupon for an SMR.

Maybe an Extra Small Modular Nuclear Reactor? We don’t need 300 megawatts yet. Maybe 30 megawatts. So a coupon for a 10XS SMR? HA! What the hell, 10 percent off?

Nvidia’s success may have something to do with the intersection of its gaming roots and human psychology. It has (historically) been operating in the development, and selling, of tools to intricately render dreamscapes and produce alternate (or virtual) realities, a particularly enjoyable area of activity, where enthusiasm is broadly contagious, and fun-and-awe is the end goal. Rather distant from “serious” gray-hair computing, boring administrative databases, sedated stiffs in suits, and closer to leather-clad boundless youthful energy, “skateboarding”, X-gaming, “revolt”, street cred.

They’ve been outstandingly successful at jointly leveraging this enthusiasm, and the underlying advanced tech (triangle shading, ray-tracing), to meet the emerging opportunities presented by AI/ML — an area perceived also via a mixture of enthusiasm, fun-and-awe, alternative realism, and some degree of apprehension and worry. It’s a great match, and well-done! I’m not too sure though that IBM’2017 (or even ’23) could have absorbed that culture without damage to either, or both.

I think it’s due to a very early realization single threaded applications were going to be overwhelmed by vast amounts of data and parallel processing was better suited for these types of workloads. But to your point, gaming was just the first application for what Nvidia refers to as accelerated computing. Totally concur on the enthusiasm, seems to be shifting to communities beyond gaming.

How much is per query cost for generative AI models? That will define the life of current AI hype. When the dust settles, how much carbon footprint these so called AI Datacenters have built? What’s the actual cost of “toying” around with ChatGPT on global warming? AI hyped cult will cancel you the moment you raise these issues.

“If the rumors suggested in the Financial Times are true, Nvidia can only make 500,000 “Hopper” H100 GPU accelerators this year (calendar 2023 is almost the same as Nvidia fiscal 2024, offset by one month) and that Nvidia was looking to ship 1.5 million to 2 million units in 2024.”

The financial Times piece continues to perpetuate questionable data.

Questionable data #1 portrays Nvidia + 1000% margin on H100. I have x4.48 over card cost at $3824 for H100 and $3302 for A100. The other half goes to hyperscale and cloud direct customers, OEMs and design build engineering for applications and systems integration cost, training, education, field support and profit. This is how Nvidia prevents a reoccurrence of the 2022 GPU channel thefts on design/build and sales sticking with Nvidia for an equal revenue cut of product value.

Questionable data #2 is quarterly production volume. I have Nvidia DC all up at 489,219 units in q1 and 1,219,449 in q2. This is calculated net into total division revenue for product volume that recoups all costs. In the so said 20 million unit’s annual server market, another industry misnomer, delivering anything less than 5 M accelerators per year is a losing objective over the near term.

I have all DC gross at $17,127 per unit in q1 and $11,279 per unit in q2. Net after R&D, SG&A, tax accrual = $8756.81 in q1 and $8,394.17 in q2.

There are two other techniques. Driving gross take back into gross equals 84,487 units in q1 and 613,509 units in q2. Or driving net into net = 99,359 units in q1 and 170,394 units in q2. I disqualify both methods because nether takes into account actual production volume required to cover all costs; R&D, SG&A and tax accrual.

Nvidia data center production volume in q1 = 489,219 units and q2 = 1,229,424.

The Financial times on low volumes is a disservice to industry, AMD, Intel, Nvidia and especially investors.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

Correction, A800 (not A100) card cost $3302. mb