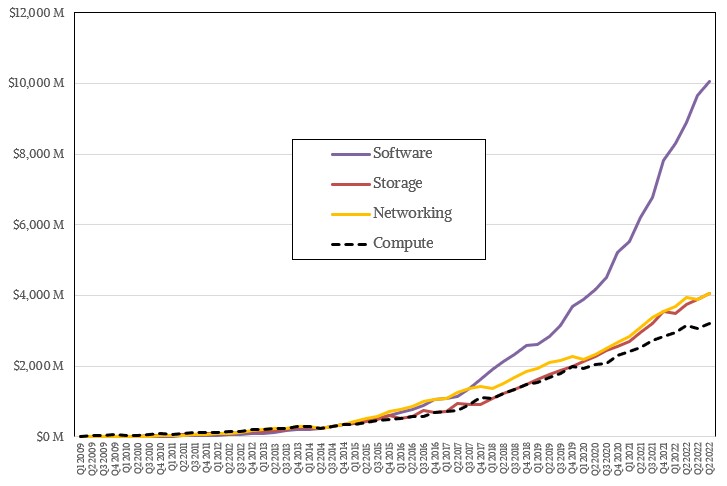

Anybody who can read a financial report knows they are paying too much for compute, storage, networking, and software at Amazon Web Services. It is as obvious as the sun at noon. And it is also obvious – and increasingly so – that the retailing and media businesses at Amazon are as addicted to the AWS profits and the free compute capacity it gives to the corporate Amazon parent as IBM has ever been addicted to the high price of its vaunted mainframe platforms.

And so Amazon and therefore AWS is stuck between a rock – increasing competition from Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud, and to a lesser extent Alibaba, Tencent, IBM Cloud, and a bunch of niche cloud builders – and a hard place – the desire to move back to on-premises IT operations, usually in a co-location facility to try to save money compared to buying cloud capacity and software.

In the past, in a nearly perfect illustration of the elasticity of demand for compute and storage, whenever the AWS business started to slow, the cloud arm of Amazon could cut price, wait a quarter or two, and revenues and profits would resume their growth. But now, AWS is not the only game in town, it is not the only one with sophisticated offerings, and it is not the only one cutting prices.

And the advent of utility-priced systems from Hewlett Packard Enterprise (GreenLake), Dell Technologies (Apex), Lenovo (TrueScale), Cisco Systems (Hyperflex and X-Series and Intersight) can not only take on AWS Outposts, but they can prevent them from ever being installed in the first place. As we have said before, datacenter repatriation is a real thing, and it is just as likely that large enterprises will get utility-priced hardware, software, and services and put stuff in a bunch of geographically distributed co-location facilities as they will move to one or more of the major cloud builders (or even a bunch of smaller ones).

But as in times past, we think AWS itself realizes that if it doesn’t help customers rein in their cloud spending, they will do it all by themselves. And Amazon chief financial officer Brian Olsavsky said as much on the call with Wall Street analysts going over the numbers for the fourth quarter.

“Starting back in the middle of the third quarter of 2022, we saw our year-over-year growth rates slow as enterprises of all sizes evaluated ways to optimize their cloud spending in response to the tough macroeconomic conditions,” Olsavsky explained. “As expected, these optimization efforts continued into the fourth quarter. Some of the key benefits of being in the cloud compared to managing your own data center are the ability to handle large demand swings and to optimize costs relatively quickly, especially during times of economic uncertainty. Our customers are looking for ways to save money, and we spend a lot of our time trying to help them do so. This customer focus is in our DNA and informs how we think about our customer relationships and how we will partner with them for the long term. As we look ahead, we expect these optimization efforts will continue to be a headwind to AWS growth in at least the next couple of quarters. So far in the first month of the year, AWS year-over-year revenue growth is in the mid-teens. That said, stepping back, our new customer pipeline remains healthy and robust, and there are many customers continuing to put plans in place to migrate to the cloud and commit to AWS over the long term.”

We think – and fully admit that it is just a hunch – that more than a few companies have figured out how to go multicloud and play AWS off against its cloud rivals, which often means not making use of high-value and high profit software services atop any particular cloud. Such software offers great functionality and ease of use, but it also ties you very tightly to a cloud. To keep optionality, it is wise to pick software platforms that can be deployed on any of the major clouds, that are available in the cloud stores with quick install and cloud licenses, and just use the clouds to get the least expensive compute, storage, and networking possible. We think that such behavior is also impacting AWS. It is more complex than just proactive belt tightening because of fears of an economic downturn. The belt tightening was going to come even in a boom time, given the high margins that AWS has enjoyed in recent years.

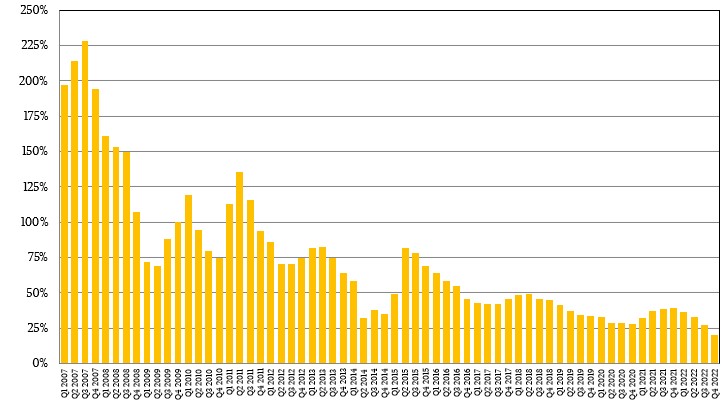

Here is just how much the top line growth has slowed since AWS was bringing in reasonable revenues in 2007:

That said, we believe the Amazon top brass when they say that companies are doing less analytics as their businesses are being impacted by the financial situation. They might be running smaller jobs for short periods of time rather than paying upfront for larger contracts for longer periods of time. This elasticity is why customers like the cloud, as Andy Jassy, Amazon’s relatively new chief executive officer who used to run AWS, correctly pointed out.

“That elasticity is very unusual,” Jassy explained, and what he said next is not precisely true anymore but you get the point. “It’s something you can’t do on-premises, which is one of the many reasons why the cloud is and AWS are very effective for customers. I have spent a fair bit of time with the AWS team on this, and we look closely at what we see. We have a very robust, healthy customer pipeline, new customers, migrations that are set to happen. A lot of companies during times of discontinuity like this will step back and think about what they want to change strategically – to be in a position to reinvent their businesses and change their customer experiences more quickly as uncertain economies emerge. And that often means moving to the cloud. We see a number of those pieces as well. And we are the only ones that really break out our cloud numbers in a more specific way. So it’s always a little bit hard to answer your question about what we see. But to our best estimations, when we look at the absolute dollar growth year-over-year, we still have significantly more absolute dollar growth than anybody else we see in this space. And I think some of that’s a function of the fact that we just have a lot more capability by a large amount, with stronger security and operational performance and a larger partner ecosystem. I think it’s also useful to remember that 90 percent to 95 percent of the global IT spend remains on-premises. And if you believe that – that equation is going to shift and flip, I don’t think on-premises will ever go away – but I really do believe in the next ten to fifteen years that most of it will be in the cloud if we continue to have the best customer experience.”

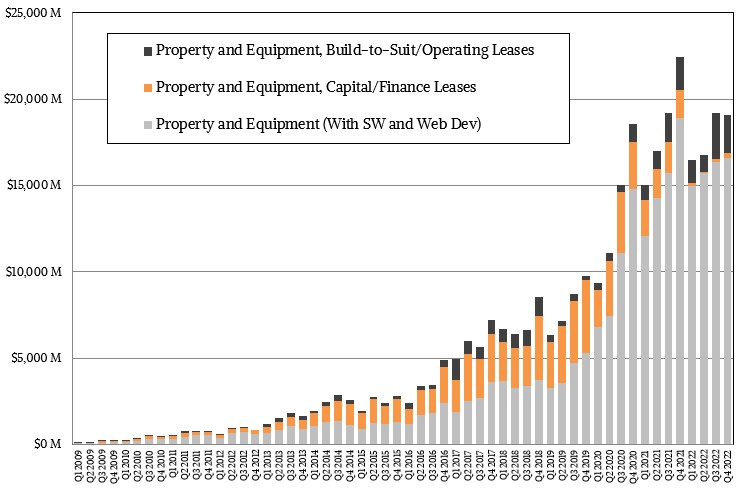

The bad news for Amazon is that this pinch is coming as the parent company is spending vast sums building its media empire and further automating and expanding its electronic retailing and grocery operations. And a $2.3 billion writeoff from Amazon’s investment in electronic truck maker Rivian Automotive certainly hurt in the fourth quarter, too, and so did a portion of the $640 million charge for layoffs announced last year that will be spread across Q4 2022 and Q1 2023.

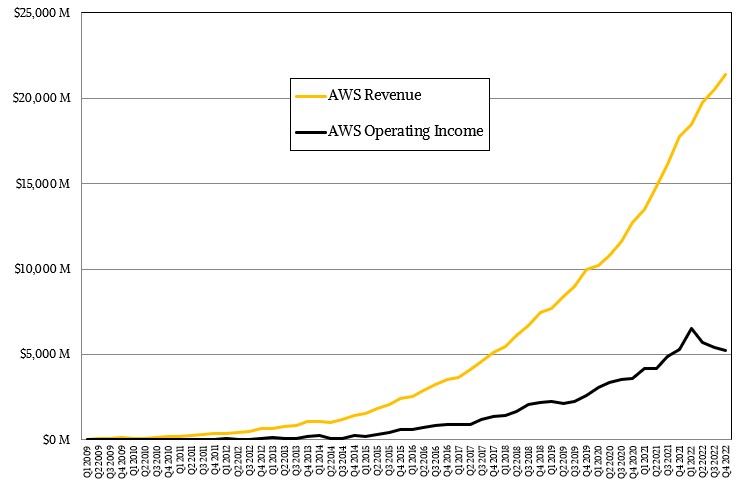

In the quarter ended in December, AWS revenues were $21.38 billion, up 20.2 percent year on year, but operating income fell by 1.7 percent to $5.21 billion. If you look at the non-AWS parts of Amazon, combined revenues were $127.8 billion, up 6.8 percent, but these parts of the company had an operating loss of $4.93 billion, significantly worse than the $1.65 billion operating loss in the year ago period.

All told, Amazon raked in $149.2 billion in Q4 2022, and had an operating income of $2.74 billion but only a net income of $278 million. In the year ago period, Amazon had a $14.32 billion net income, with $11.47 billion of that coming from recognition of its investment in Rivian, which had gone public. The air is coming out of that tire as Rivian is struggling with quality control issues.

As we have said many times, Amazon is a platform provider and increasingly an application software provider as well as a place where companies run their own code or that of others. That software is extremely sticky, and for many, the only practical way they can get started on advanced technologies is to do so on a cloud like AWS. And frankly, for many workloads, it really comes down to choosing between AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. And once these workloads get strategic enough and big enough, they start looking at ways to cut the bill and better integrate disparate systems and circumvent egregious data egress charges.

Most of the cloud versus on-premises arguments fail to address tge main reason cloud has a major advantage – workloads run with much better performance in the cloud as it can leverage a slew of innovative services like highly scalable, high performance databases such as Dynamo DB NO SQL, Redis and Elasticache in-memory databases, Redshift data warehouse, Elastic Map Reduce, Lambda serverless, etc. When your competitors are using those services you’re left with no other choice.

That argument doesn’t really stand. Many of the cloud provider services are not really faster then the on-premises equivalents one good system engineer would configure. And there are alternatives for all services out there, in one shape or the other.

What the real advantage of any cloud provider is, is to reduce the cost of operating infrastructure and those services. So in order to have a multi-az like setup of Elasticache/Redis one would need to:

– configure 2 servers in 2 distinct datacenters

– have replication in between them

– configure proper backups

– configure proper monitoring

– configure proper failover on the LB level

– have those LBs in the first place

– etc.

With AWS, that is just a few clicks. So in order to provision the whole thing there from scratch, you need like 30 minutes, while on-premises, assuming you don’t have many pieces of the tech stack solved yet, days.

This is the valuable difference, especially when you want to cut time-to-market. But when you have large internal IT, of really competent people, things get automated, streamlined, the difference starts to disappear. This is why large companies are sometimes choosing to go back on-premises, because inflated per-hour price (even with huge discounts and contracts in place) is outweighing the benefits or the convenience services provide.

Even if the mentioned performance difference was true, microsecond difference between company A and its competitor is negligible.

All that being said, each company has its own set of reasons why would they choose one way or the other, and that is fine. What I hope to see though is fair amount of the competition in the space, because that is good for all of us.

Wow, we just found the dumbest comment on the internet today. Are you that naive that you seriously don’t think that those same concepts could be adopted on premise, or are you just AWS certified, like the old CCNA boys club of last century?

I guess you have never run modernized workloads on the cloud.

To take advantage of cloud, enterprises have to switch to serverless/ephemeral infrastructure and automation. If they use cloud just like they use their data center, cloud will be more expensive.

Businesses need to critically make cost benefit analysis as to best approach for resource utilization.

Be it FaaS,SaaS,PaaS,on-prem or even a combination of different approaches. What’s important is that it must suit business goals.

What about blackbird

The cloud is vastly overcomplicated and more expensive for the majority of businesses. Cloud vendors such as AWS and Microsoft have been screwing customers for years with their excessive compute, storage and transfer costs. Clouds, like EVs, should be cheaper – not more expensive. The economies of scale of these providers should make their services cheaper than buying and managing your own hardware. Servers are good for at least 5 years nowadays and running on-prem can be more cost effective for most businesses. Cloud vendors need to drastically simplify cloud utilization by eliminating the nickel and diming. The article is right that businesses should only use the least common denominator features that can be easily migrated among vendors. Avoid lock-in to keep your freedom to choose!

Workload characterization will become a key enabler, backed by policy & cost ontologies. Optimizing for cost on alternate platforms is one among many reasons for cloud native ideology. “Cloud” may become a legacy denotation. Metadata management will return as a cross-functional enterprise discipline. The major cloud providers may have to reconsider their preference for service automation over human-enabled services. If so, recent layoffs of trained personnel will prove to have been a strategic error of significant proportions.

Mid 22 was a bad time for all….come on man

It seems this repatriation is in the heads of a few people. Cloud vendors continue to grow strongly and the media takes some examples of clients moving work to DC and portray it as repatriation. May be its a stop gap. They want to bring the workload in, modernize it and then migrate to cloud again. The interesting aspect is cloud vendors are so big and successful they dont really care for anyone and therefore, everyone, even this portal, needs to be in good books of dying on-premise vendors which are gleefully mentioned in this article. Just because these dinosaurs have offerings doesnt mean clients should buy. We portray cloud vendors as screwing customers, have we forgotten IBM, HPE, Oracle, DELL? Are cloud vendors worse than these? I cant believe that.

Depends on what clouds you are talking about. IaaS, PaaS, SaaS. SaaS can be considerably cheaper for businesses, and better, though they do have to do due diligence on and watch egregious compute, data, storage and transfer charges. That would be true with on premise too, but with cloud customers tend to forget until a big bill hits.

Public Cloud is just another marketing term for outsourcing i.e. giving part or all of your IT environment to a vendor for a fixed and/or variable cost per month based on actual usage. Like outsourcing, there are pro’s and con’s. More often than not, it is a company financial decision to shift CAPEX $’s to OPEX $’s. However, one needs to remember that the outsourcing model is based on low cost of entry, with increasing costs based on inevitable change requests and/or additional customization required to address rapidly changing business requirements. Big push in large enterprises today is to leave small amount on Public Cloud, but shift the big, critical stuff to on-prem control using collocation vendor provided DC’s. Best of both worlds. Having stated this, on-prem solutions do require a new service model that is competitive with some aspects of public cloud. As example – adopting COD (capacity on demand) solutions that have been around for decades.