If you want to figure out what is going on with spending on the corporate datacenters of the world, a good place to start is to examine the financial results of Hewlett Packard Enterprise and Dell Technologies, which are still the two largest original equipment makers for servers in the world.

Lenovo and Inspur, both based in China with substantial operations in the United States and Europe, have aspirations to bypass HPE and Dell, but thus far that has not happened.

In any event, HPE and Dell reported their financial results before the Labor Day holiday in the United States and the bank holiday in Europe and we are getting around to analyzing what is going on in their numbers to get a better sense of what is happening with the server, storage, and networking supply chains and with the appetite for spending among organizations outside of the hyperscalers and major cloud builders.

We say outside of the hyperscalers and cloud builders, who represent about half the server volumes in the world and a little less than half the server revenues, because these companies have not bought machinery from Dell or HPE for a long time. The Super 8 datacenter operators – Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, Google, and Meta Platforms in the United States and Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent, and ByteDance in China – have long since designed their own machines, bought their own parts, and shipped them to original design manufacturers such as Quanta, Inventec, Foxconn, WiWynn, and the custom server arms of Lenovo and Inspur for the machines to be made at the lowest possible costs.

There is no way that HPE and Dell can ever get that business back, given the machine volumes the Super 8 require and their inability to pay any kind of reasonable margin to their server manufacturers. HPE and Dell walked away from sales of low margin, minimalist machines because they can’t afford to chase such deals and make it up in volume like the ODMs seem to be able to do because they have so many other contract manufacturing deals for consumer, networking, and other gear.

This means that HPE and Dell ride the spending waves of the enterprise, service providers, telcos, HPC centers, and government and academic customers who individually have orders of magnitude lower volumes than a hyperscaler and cloud builder and therefore pay a premium for their machines. Not much of one, mind you, as the financials from HPE and Dell have shown for years.

What has been hard to discern for the past two and a half years is how much actual demand in its own right has been rising and falling and how much supply has crimped demand because of parts and manufacturing capacity shortages. The counterbalance to this is that hyperscalers, cloud builders, service providers, and large enterprises have had to work with semiconductor makers and their ODM or OEM partners to plan their capacity two years out, with some parts shortages at 52 weeks to 72 weeks. So never before have the OEMs and ODMs had justifiable cause to twist customer arms to tell them what their capacity plans are. Planning is easier, with an overlay of uncertainty that is always part of the economy during a pandemic and a war.

None of this is easy, and the organizations of the world that are dependent on compute – meaning, all of them – should be thankful that someone is still willing and able to bend metal around silicon and provide support for it.

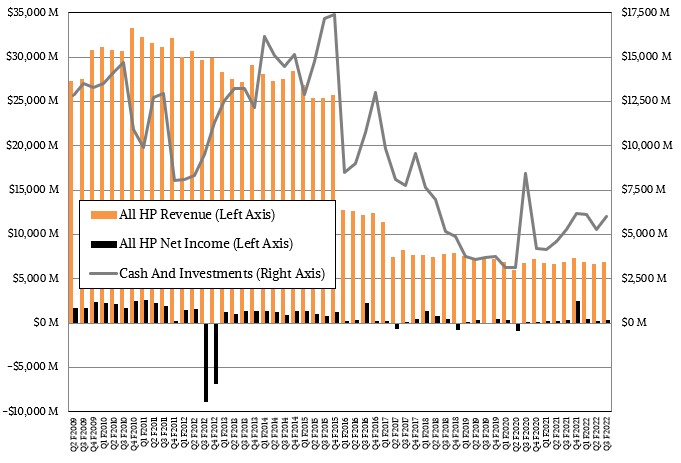

In the quarter ended July 31, which was HPE’s third quarter of fiscal 2022, the company reported sales of $6.95 billion, up eight-tenths of a point from the year ago period, and net income of $409 million, up 4.3 percent. That net income represented 5.9 percent of revenues, which is a little higher than average for HPE.

The company exited the quarter with $6.03 billion in cash in the bank, which is a healthy amount of cash.

Tarek Robbiati, chief financial officer at HPE, bragged on the call with Wall Street analysts that the 13.3 percent operating profit for the Compute division was “by far the most profitable compute server business in the industry,” and that it was 2.1 points higher than the year-ago quarter.

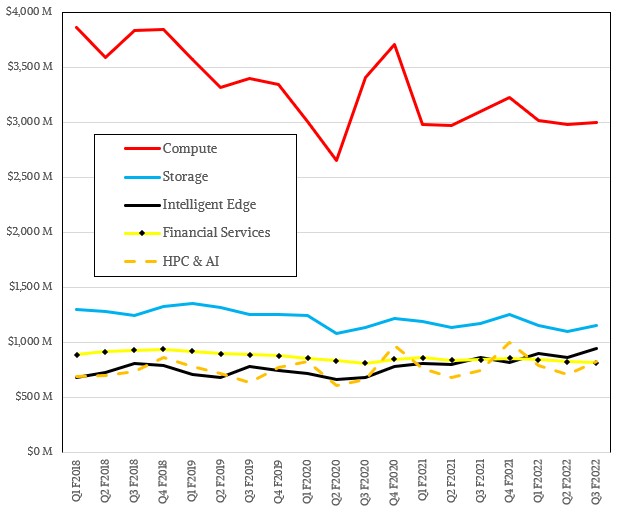

In the quarter, the Compute division, which is mostly sales of X86-based ProLiant servers, rose by six-tenths of a point sequentially to just a hair over $3 billion, but sales were actually off 3.2 percent year on year. Earnings before taxes for Compute were $400 million, up 15.3 percent, but down 3.6 percent sequentially.

Component pricing and shortages are still making it hard to tame margins, but HPE seems to be doing about as good of a job as any company could do under the circumstances. The company’s strategy is what you would expect: It is pushing what it has on the truck and not talking about what it doesn’t have, and pushing the richest mixes of CPUs, storage, peripherals, and financing that it can.

“The supply chain dynamics remain largely unchanged,” Antonio Neri, HPE’s chief executive officer, said on the call with Wall Street. “But what has changed for us is that over the months in the quarter is that we have taken actions to dual source or to steer demand in our products and then obviously implement design changes. I think because of our combination of our portfolio and customer segments, we believe we are very well positioned to move forward through this challenge as we go into next quarter and into 2023. But we expect supply to remain challenged as we get into 2023.”

HPE is not being specific about its Compute backlog, but says it is five times the normal level right now and that it grew sequentially from Q2 to Q3 of the fiscal 2022 year. Robbiati said that HPE expected a sequential revenue bump in Compute revenues in the final quarter of the fiscal year due to some multi-sourcing for components and the “demand steering” mentioned above.

The HPC & AI division had sales of $830 million, up 12 percent thanks to some big deals for its “Shasta” Cray EX supercomputing systems, but earnings fell by 3.4 percent to $28 million.

This division also sells big NUMA machines based on SGI and HPE chipsets and services the legacy Integrity line of machines that run OpenVMS, HP-UX, and Tandem NonStop operating systems, but we think at this point their contribution is nominal excepting NUMA machines for running large ERP systems and SAP HANA in-memory databases. The backlog for the HPC & AI division has held pretty steady at just under $3 billion, so it is booking revenue about as fast as it is recognizing it.

The core ProLiant business is just a tad under 4X more profitable per dollar of revenue as the HPC & AI business, which is consistent with our observation that it is very difficult indeed to make a profit out of HPC simulation and modeling. But, as we often say here at The Next Platform, someone has to build and support these systems. The NUMA iron is very profitable, we think. In any event, Robbiati said on the call that HPE would recognize some big deals in the fourth fiscal quarter and that its margins in HPC & AI would expand. But they will inevitably contract along the choppy curve we have observed in more than three decades of watching the HPC sector.

HPE’s storage business, which is comprised of acquired 3PAR, Nimble Storage, SimpliVity, LeftHand Networks, and others storage products as well as homegrown stuff, had a 2 percent decline in the quarter to $1.15 billion in sales, with earnings of $169 million, down 5.1 percent. Operating profit is 14.7 percent of revenue, also up 2.1 points year-on-year. HPE said it was running a record backlog in storage, but as with its Compute division, it did not provide a figure.

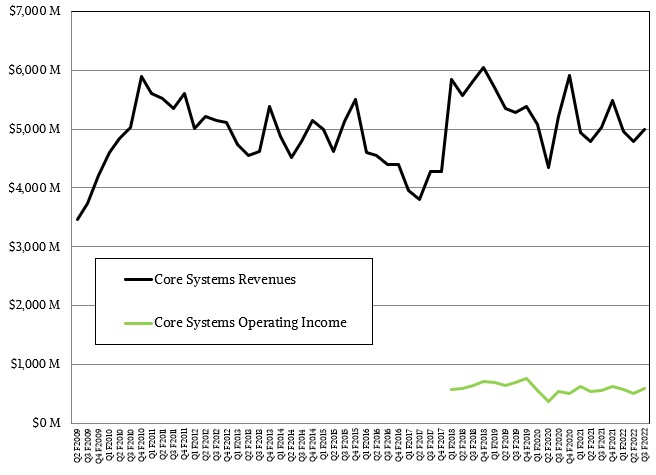

For as long as HPE has been selling systems, we have been keeping an eye on its core systems business, and our latest dataset has tracked system sales in the aggregate since the Great Recession in 2009. We reckon this was a kind of line of demarcation between an economy in one phase and then in another one, much as the Great Infection of 2020 will probably yield another line of demarcation.

Over the decades that core systems business has had many different components and architectures, and in recent years it has held pretty steady at around $5 billion a quarter, more or less. In the third quarter of fiscal 2022, that core systems business had $4.99 billion in sales, off seven-tenths of a point, and earnings of $597 million, up 7.8 percent. Ideally, companies want earnings to grow twice as fast as revenues, which are also growing, but in this environment, holding revenues steady and growing profits is the second best option.

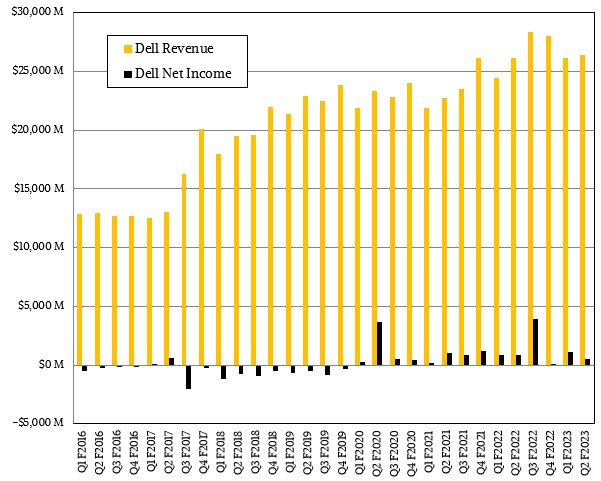

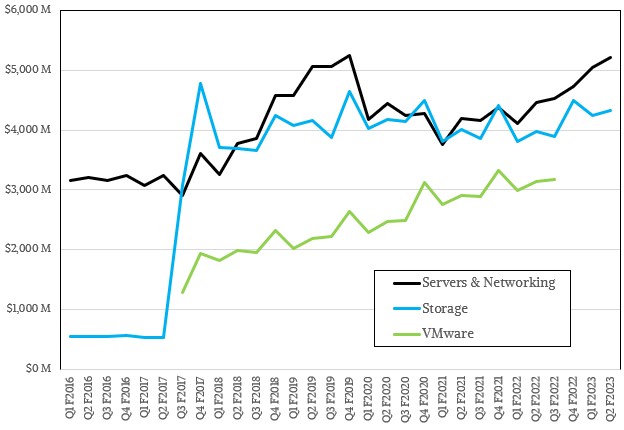

Dell was taken private a bunch of years back and we lost some visibility into it, and so our dataset only runs from its fiscal 2016 year, when it went public again, until now, its fiscal 2023 year, which will end in January 2023.

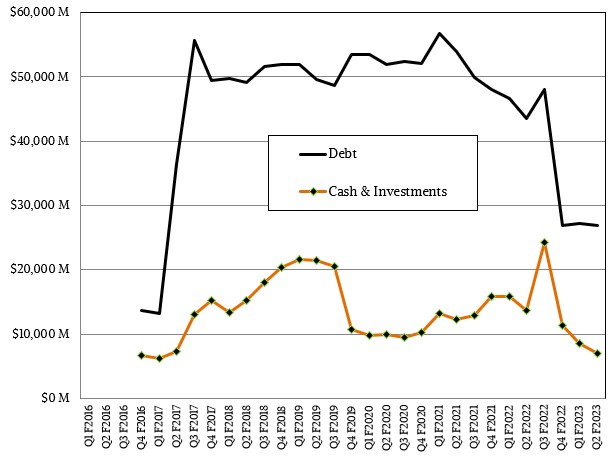

Both Dell and HPE were IBM wannabes in the 2000s and 2010s, and they acquired all kinds of software and consulting businesses to try to mirror Big Blue. And when that did not raise the profits expected, HPE sold off its software, consulting, and PC businesses and Dell did similarly with its software and consulting businesses but kept its PC business. Argue what you might about this strategy, but Dell has a much larger supply chain and has been able to wield that to push its sales of servers, switches, and storage well beyond that of HPE. And that is not including VMware, which it took control of through its $67 billion acquisition of EMC back in 2015.

Last fall, VMware was spun off into a separate company, refilling the personal coffers of its largest shareholder, Michael Dell, and the core Dell server and switching and EMC storage businesses are still plugging along, albeit with different brand names. And Dell, the man, has long since reached his aspiration of bypassing IBM and then HPE as the dominant provider of hardware platforms in the datacenter.

What do you do as an encore to that?

In the second quarter of fiscal 2023 ended in July, Dell’s Server & Networking division had sales of $5.21 billion, up 16.7 percent, and its Storage division had sales of $4.33 billion, up 9 percent. Operating income is not posted for either division. But the combined Infrastructure Services Group had sales of $9.54 billion, up 13.1 percent, and operating income of $1.05 billion, up 7.8 percent. That operating income represented 11 percent of datacenter hardware sales, which is about typical of Dell for the past five years.

We don’t care about its PC business much except that it gives Dell leverage with chip makers like Intel, AMD, and Nvidia – leverage that HPE gave up, and possibly to its chagrin looking at the relative size of the datacenter businesses of the two companies at this point. The Dell Client Services Group has about half again as much revenue and roughly the same profitability as its Infrastructure Services Group, which is pretty good considering how messed up the world’s supply chains have been.

With VMware out of the mix, Dell’s presence in the datacenter is diminished, and it never made a lot of sense for Dell, the company, to let go of a VMware it paid so dearly for. But it surely made sense for Dell, the man, to take it public and reap that special dividend for shareholders. At the very least, Dell is back to being essentially a pure hardware player, so it has eliminated some difficulties for VMware and its many other hardware partners.

The sale of VMware also helped Dell eliminate some of the massive debt it was carrying as part of the EMC/VMware acquisition. In fact, Dell’s debt level is roughly equal to a quarter of revenue – the same level it was at in fiscal 2016 before the EMC/VMware deal was completed. So with everything unwound except the EMC storage business, Dell is now twice as big with twice as much debt. Maybe that was the plan all along. But we suspect that Dell, the man, had higher aspirations than turned out to be possible.

As far as ISG goes, this was the seventh straight quarter of revenue growth for Servers & Networking and the sixth straight quarter of revenue growth for Storage, which means the coronavirus pandemic did not have much of an effect on Dell despite the supply chain woes and economic tumult. Interestingly, the company’s APEX subscription pricing for hardware now has an annualized run rate of over $1 billion, and the orders for APEX were up 78 percent in fiscal Q2.

We wonder how long it will be before half of HPE’s core system sales come from GreenLake subscriptions and half of Dell’s ISG sales come from APEX subscriptions. That is a new race that is a-foot, and one that HPE has a head start on and can win. Some might say must win. With all of HPE’s software, services, leases, and GreenLake infrastructure subscriptions together yielding only an $858 million annualized run rate as the July quarter ended, and only 27 percent of that, or about $232 million, being for GreenLake subscriptions, Dell, which started later with hardware subscriptions, has a business that is at least 4.3X bigger.

Given the benefits of hardware subscription pricing, we are surprised these numbers are both not higher.

Be the first to comment