Somewhere nearly a decade ago, we made a joke when looking at the rise of the hyperscalers and cloud builders. Here is the joke: “We used to worry about there only being ten vendors who supply servers, with most of the revenue being generated by two, maybe three, of them, and none of them making any money at all. Now we worry about there being only eight buyers of servers worldwide with the rise of the hyperscalers and cloud builders, and not even the chip suppliers will be able to make any money.”

This joke has not precisely come true. But something like this is playing out in the datacenter, with the relative few big buyers setting the pace of innovation because they set the pace for consumption, and as such, they set the level of profits that companies can command. Sometimes, these huge compute utilities buy a lot of stuff and sometimes they cut back, and when they do, it really shows.

For instance, during Intel’s third quarter ended in September, and probably even more so in the fourth quarter we are in now.

Intel has been beating Wall Street’s expectations – which were generally higher than its own expectations, and quite possibly engineered that way – for so long that beating expectations became the new expectation. We don’t give two whits about expectations except when companies are managing to them a bit too much. For instance, if Intel is selling off the flash storage business that has been a drag on profits but a contributor to revenue to SK Hynix for $9 billion, it seems precarious to announce a $10 billion share buyback program that more than wipes it out.

Shouldn’t that money be invested in creating great chips and maybe getting the Intel foundries etching chips with the best of them? Meaning, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp? This smells of the same kind of financial engineering, essentially rewarding shareholders before great things happen so they believe and the stock rises in price, that has hurt IBM for decades. What Intel actually needs to do is focus on actual engineering to create a profitable future. Intel needs to engineer its financial future, or better still, finance its engineering future, not financially engineer its future. That $9 billion from SK Hynix should be used to make a fab that in turn makes fabulous chips. The ink is not even dry on the flash deal, the money is not even in the bank yet, and Intel’s top brass have already spent it – and more. And it is just finishing off most of a $20 billion stock buyback authorization that was put into effect a year ago.

This doesn’t make sense for Intel now any more than it did for IBM two decades ago or even one decade ago.

All we know for sure is that Intel didn’t beat Wall Street’s expectations in Q3 2020 – even if it did beat its own – and it has had to reset them somewhat abruptly for Q4 2020, and that is causing a certain amount of heartburn. Like Data Center Group stomaching a 25 percent decline in Q4. That kind of heartburn.

In the September quarter, Intel’s sales were $18.33 billion, down 4.5 percent, operating income was $5.04 billion, off 25 percent, and net income was $4.28 billion, down 28.6 percent. And Intel can’t blame the PC business entirely, which is relatively healthy thanks to COVID-19 and despite intense competition with AMD, with sales up 1.4 percent to $9.85 billion but operating income off 17.4 percent to $3.55 billion.

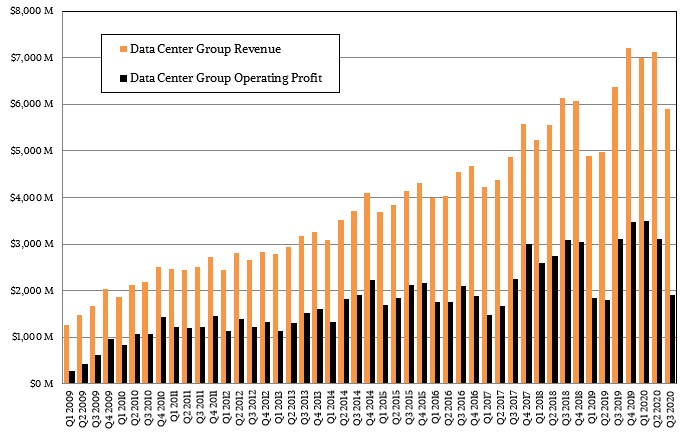

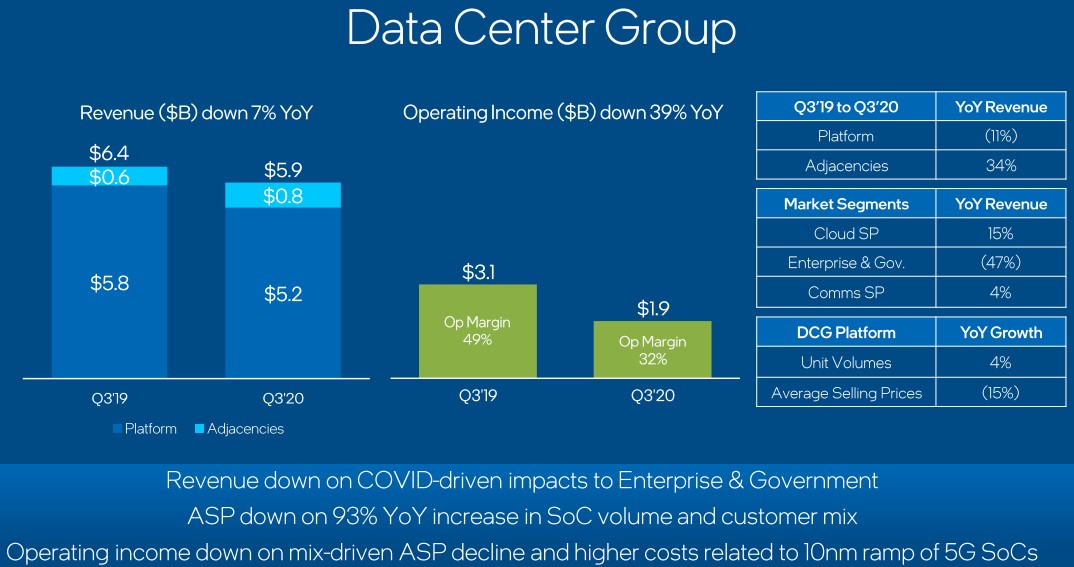

Core platform sales – meaning server processors, chipsets, motherboards, and a smattering of systems – for Data Center Group were $5.15 billion, down 11.5 percent, and adjacency sales (meaning network switches and their chips plus network adapters and their ASICs plus a bunch of other stuff) were up 33.7 percent to $754 million. (With think the Intel 800 Series NICs are doing relatively well among a few hyperscalers and cloud builders.) Add it up, and Data Center Group revenues fell by 7.5 percent to $5.91 billion.

Intel chief executive officer Bob Swan, who used to be the company’s chief financial officer, said that the 47 percent decline in Data Center Group revenues among its enterprise and government customers (which also includes educational institutions) was sharp, particularly considering that revenues in this segment rose by 30 percent in both Q1 and Q2 this year. Cloud service providers – what we call cloud builders and hyperscalers individually because they are different – only spent 15 percent more year on year, and communications service providers – telcos and cable companies –saw only 4 percent growth. And looking ahead to the fourth quarter, there will be that 25 percent decline across the board as various factors set in.

Intel says that unit volumes in Data Center Group rose by 4 percent in the third quarter of 2020, but that average selling prices (ASPs) across all components sold fell by a very harsh 15 percent due in part to a mix shift away from big bad chips like Xeon SPs and towards SoCs in the datacenter – presumably Xeon D chips and the like. While what Swan and chief financial officer George Davis said in their call with Wall Street analysts in this regard is true within its own Intel Inside world, it doesn’t tell you what happened and why in the world at large.

There are a few possible scenarios. But the most obvious one is that this is not a mix shift within Intel’s product line, but an increase in SoC sales that is separate from a decline in Xeon SP sales, the latter being likely caused by increased competition from AMD’s Epyc processors. We will know as soon as AMD reports its financials on October 27. And what we suspect is that Intel is doing a good job selling compute for the 5G buildout but is slipping a little in the datacenter proper. A little slip for Intel could mean slashing prices and therefore cutting revenue as well as losing deals to AMD. This lost money does not always translate into sales for AMD, but sometimes it does, and it is most definitely being caused by the “Rome” Epyc 7002 processors in the field by AMD and the “Milan” Epyc 7003 processors that are impending.

Considering that the hyperscalers and cloud builders should be getting their first 10 nanometer “Ice Lake” Xeon SP processors about now, well ahead of the formal launch early next year, and they are well aware of the 10 nanometer “Sapphire Rapids” Xeon SPs that will come shortly after them next year, it would be natural to think there would be a slowdown about now. Hyperscalers and cloud builders spent big in Q3 and Q4 last year, and the compares were going to be tough anyway. And given the economic climate, it is not at all surprising that enterprises, governments, and academic institutions all might take a pause about now after doing a bit of spending to cover their additional computing needs during the early months of the coronavirus outbreak.

That Intel is seeing a “digestion” phase coming at the hyperscalers and cloud builders in Q4 might have more to do with the expected price/performance advantage of Milan over Ice Lake and maybe even Sapphire Rapids, which either forces Intel to cut prices or lose deals, than it does with a loss of appetite. In that sense, what is really happening is that Intel’s customers might develop a a touch of indigestion, and maybe will be able to consume stuff from others just fine.

Either way, as we remarked many years ago, Intel’s revenues and therefore its profits with Xeons has to go down. But for every $5 that Intel loses because of indirect or direct competitive pressure, AMD might only pick up $1. The funny bit is that $1 will double the size of its server business, which can keep applying pressure and then grow by 75 percent, then 50 percent and then by 25 percent and then by 10 percent in the following years until – guess what? – AMD has 20 percent server CPU market share and maybe 15 percent revenue share in what comes out to be an only slightly larger revenue pie for all X86 server CPUs sold. The units will scale up nicely, but the revenues will not track up with it. ASPs will not rise faster than shipments again until one CPU vendor has hegemony control again or something interesting happens with CPU and server architectures that commands it. Arm server processors from Ampere Computing, Marvell, Huawei, Amazon, possibly Nvidia, and a few others will eat into that core CPU demand, and so will the rise of SmartNICs and DPUs that offload tasks from CPUs and the network.

In fact, with the edge buildout, it seems far more likely that overall ASPs for compute in the “datacenter” will come down, and possibly quite hard. There will be 2X or 3X or maybe more aggregate compute installed at the edge of the datagalaxy than at the core.

So, no kidding. Those Data Center Group ASPs are going to come down over time, even when hyperscalers and cloud builders and HPC centers buy beefy CPUs for their distributed computing systems. Get used to this slide.

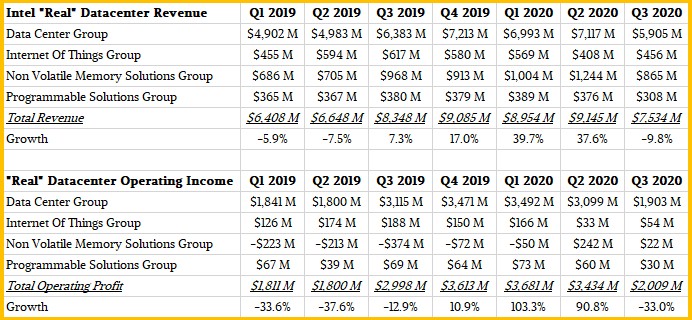

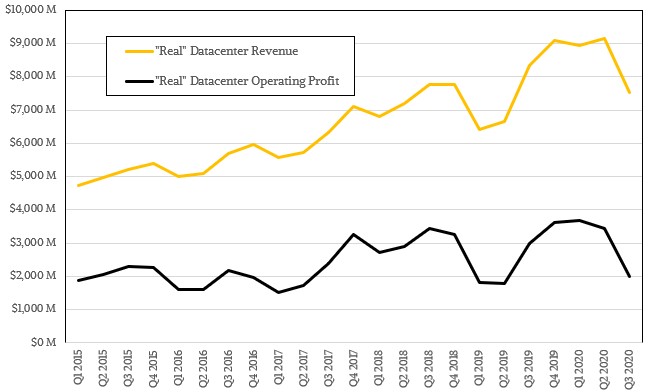

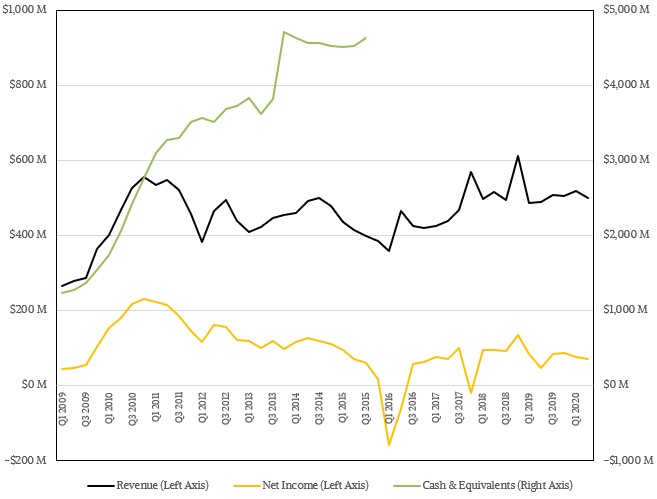

It is pretty obvious that a lot of the hardware and software that Intel sells is focused on the datacenter/edge computing environment (as distinct from client devices) and we have always tried to give a rough reckoning of what this “real” datacenter business looks like each quarter. Here is a table that shows our allocations of revenues by Intel group as they relate to the datacenter, and this presentation is different from (but akin to) the “data-centric” discussion that Intel has been giving in recent years. Once the flash business is sold off, these tables and charts will change to the tun of $1 billion or so a quarter, and operating profits should improve a bit.

Here’s the table for all of 2019 and the first three quarters of 2020:

And here is a chart that shows the ups and downs of this “real” datacenter business at Intel since we have been modeling this since the beginning of 2015:

Selling off the flash business to SK Hynix will shift the orange line down by a bit and the black line up by a smidgen. That’s moving the lines in the right directions. Intel just doesn’t have the flash volumes to compete in that game, and it needs to up its CPU game.

There is one other chart we wanted to share as part of our analysis, and that is for Altera and then Programmable Solutions Group, the FPGA unit that Intel acquired five years ago for $16.7 billion. Take a look:

Our data for Altera goes all the way back to the beginning of the Great Recession, and we have very detailed financials that show product line ramps that Intel stopped giving when it acquired Altera. So, here’s our observation. We like FPGAs. They are neat and useful. But the trajectory of Altera has not really been changed much by being a part of Intel. Whatever Intel thought might happen with FPGAs when it spent all of that money on it did not happen. Which should give AMD pause as it considers buying Xilinx. But, then again, AMD will double its datacenter and embedded businesses combined if it buys Xilinx, and that is not a bad way to spend a very high market capitalization down if this rumored deal goes through.

“This smells of the same kind of financial engineering, essentially rewarding shareholders before great things happen so they believe and the stock rises in price, that has hurt IBM for decades.”

A curious point of commonality between the two (IBM and Intel) is that they are (were) both being led by financial engineers, rather than any actual engineers.

Well, yes and no. While it is true that Intel got into its worse troubles when Paul Otellini and Bob Swan were at the helm, the damage was done and that’s how they got the jobs.

Also, Louis Gerstner has a bachelor’s in engineering from Dartmouth, and while Sam Palmisano has only a BA from Johns Hopkins, Ginni Rometty has a BS in computer science and electrical engineering from Northwestern University.

Agreed on the degrees, which is often just a label for some. I was implying more of the approach to managing the companies. To be contrasted against Lisa Su, for example. Or Morris Chang. Lee Seok-Hee, the SK Hynix CEO…

“Financial engineering” . . .

TPM quarterly opens with an image of the illusive ‘P’ variant integrating FPGA has never been seen in the channel, nor on any Intel shipping product list I’m aware. 6138P does not appear to exist other than an artist’s depiction?

“Intel says that unit volumes in Data Center Group rose by 4 percent in the third quarter of 2020, but that average selling prices (ASPs) across all components sold fell by a very harsh 15 percent due in part to a mix shift away from big bad chips like Xeon SPs and towards SoCs in the datacenter – presumably Xeon D chips”

Pursuant Xeon D, Broadwell ‘gen 1’ sold 342% greater than Skylake generation 2 and Intel move back to a Broadwell architecture, is that right, generation 3 shows not much, 1602 and 1622 are 2.19% of Skylake generation. The category appears rejected.

Think about it. When is the last time anything concrete could be learned from Intel, at OCP for example, about Xeon D? And doesn’t ARM World run the network edge?

On Xeon Scalable volume, channel shows a 7% increase in total volume q2 to q3. However through q3 Xeon represents 63% of all Intel channel CPU inventory.

On channel data Xeon 1K average weighed price (which is not ASP nor gross on the customer sale) slipped 10.46% q/q; $2383.47 to $2133.13 which is all about Scalable Skylake shipping at 6.6 to 1 in relation Cascade lake.

“I don’t know where Mr. Swan get’s his financial engineering”, however normalizing on channel data to reach INTC 10K certified division revenue statement, 37.58% DCG and 62.42% CCG respectively, Xeon margin slips 28% q/q. From 70% off 1K to 98% off 1K.

Through q3 Xeon sells for variable cost $42.66 each. If Ice Lake sold, where there is none recorded on channel data, in volume equivalent to 20% of XSL/XCL holdings, Intel priced Ice Lake at the marginal cost or producing every next unit $60.

DCG made no Xeon gross, or net, in q3 2020.

. . . so much for financial engineering.

Intel 10K often presents an invented reality. Get a glimpse of Intel real world, AMD too, at Server Today;

https://seekingalpha.com/instablog/5030701-mike-bruzzone/5509267-server-today

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

“it seems precarious to announce a $10 billion share buyback program that more than wipes it out.”

That was a continuation of the $20B share buyback announced Oct 2019.

“Whatever Intel thought might happen with FPGAs when it spent all of that money on it did not happen.”

The 10nm issues slowed the arrival of Agilex FPGAs. Intel seems to be making good use of FPGAs in 5G. We’ll have to see what the Stratix 10 nx does for AI.

Intel uses their FPGAs for development of new technologies … PCIE5/CXL was done in 2019, for example. The PAM4 development will also be important for PCIE6. The EMIB development is showing up in their Xe GPU tiled designs.

IBM man and Chipzilla no more…but I agree managing for a steady slide in relevance to appease short term financial investors is not the way to do things..

I was at IBM when Akers left and Lou came in. He did a 180 on the strategy, laid a bunch of people off and started from the bottom to save the company. Seems like something needs to happen at Intel