It is hard to remember sometimes way back when, in 2008, as Nvidia first took a stab at GPU compute in the datacenter with the original Tesla GPU accelerators and a very rudimentary CUDA programming environment for offloading parallel algorithms from CPUs to GPUs. It has been a long road from inventing the GPU to accelerate gaming to reinventing the GPU to be the most diverse and powerful math coprocessor we have ever seen – and the shiny new “Ampere” GA100 GPU is precisely that. Again.

Intel and AMD are going to have to bring their A games to compete against Ampere and its follow-ons in the coming years, and the wins that both Intel and AMD have had in the exascale generation of machines at the biggest supercomputer centers of the United States suggest that maybe, just maybe, there will be some hefty competition between these three GPU makers in the coming years. But for now, Nvidia still rules GPU compute in the datacenter. And adding Mellanox and Cumulus Networks is not only giving Nvidia a chance to engineer for its vision of the datacenter as the unit of compute, as we discussed recently with Nvidia co-founder and chief executive officer Jensen Huang right after the Mellanox deal closed a month ago, the Mellanox acquisition, to the surprise of many, is giving Nvidia a very fast growing – and very respectably profitable – networking business to expand and bolster its datacenter business right now.

The financial contribution that Mellanox made to Nvidia before the deal closed – by making money and keeping it in the bank, thus lowering the effective price tag for the acquisition – cannot be underestimated. When the deal was announced back in March 2019, Nvidia was adamant that it was going to burn $6.9 billion of its $7.4 billion cash to do the acquisition, and then get back the $553 million in cash that Mellanox had in the bank at the time, for a net cost of $6.37 billion.

But a funny thing happened on the way through the antitrust regulators of the world. In the year and change since the deal was announced and when it was closed on April 27 this year, the Ethernet switching business took off at Mellanox at the same time as its sales of ConnectX and Bluefield SmartNICs exploded and InfiniBand products ramped nicely from EDR 100 Gb/sec to HDR 200 Gb/sec speeds. Mellanox, under tight controls because of the pending Nvidia acquisition and sitting on the right products at the right time, became profitable as it always wanted to be and never was. And Mellanox ended the March 2020 calendar quarter with $938 million in the bank after pulling 27.2 percent revenue growth, to $1.45 billion in sales in the trailing twelve months that the deal was pending. That added another $385 million to the kitty, and lowered the Mellanox net price to $5.98 billion.

And, as we expected when the deal was initially launched, in April of this year, when the coronavirus pandemic was really taking hold worldwide and interest rates were very low, Nvidia issued $5 billion in unsecured notes to boost its balance sheet – a wise move during a recession. That made the net hit to Nvidia’s cash pile, which had grown to $16.35 billion including that financing and the cash pile it had generated during the year of waiting for the Mellanox deal to close, negligible. After paying for Mellanox on April 27, Nvidia had $10.4 billion in cash and will be adding somewhere north of $1.2 billion to cash per quarter. In other words, it will be able to make enough money to cover the net Mellanox acquisition price in about five quarters and have a much broader story to tell with its datacenter business, which broke through $1 billion in the first quarter of fiscal 2021 ended April 26. That’s the first time that datacenter business has broke through that $1 billion barrier, and there are no Mellanox numbers in there to helping. There will be next quarter, for sure. And ever quarter after that.

So, let’s take a minute and talk about those Mellanox numbers.

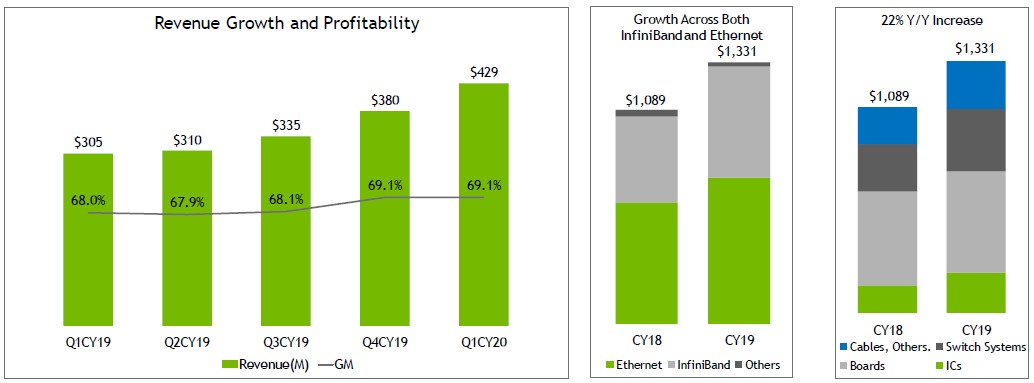

In the first quarter of 2020 ended in March – which is the last time that we will see Mellanox numbers as free standing – revenues rose by 40.5 percent to $428.7 million and net income rose by 2.18X to $105.9 million, which was a very healthy 24.7 percent of revenues. And the prior year, as you can see in the chart above, was one of steadily improving growth and steadily improving profitability. Mellanox had finally hit its stride after massive investments in its Ethernet switch business, continued and steady investments in its InfiniBand business, and widespread adoption of its SmartNICs by those hyperscalers and cloud builders who are not making their own. If the $6.9 billion acquisition looked pricey – in no small part because Marvell and Intel were also both trying to buy Mellanox when Nvidia jumped in – back in March 2019, it looks like a very good decision here in May 2020. But no one could really know that, either inside of Mellanox or Nvidia, because a lot of things had to happen for Mellanox for this breakthrough to occur. There was no doubt hope that precisely what did happen would happen, and it would have been remarkably good timing for Nvidia if the deal only took six months to close instead of thirteen. But, as it stands, Nvidia is having a pretty good run on its own right, so all’s well that ends better.

In the first quarter of 2020 for Mellanox, based on the statements that the company made a month ago, the InfiniBand business – including chips, boards, switches, cables, and network interface cards attached to InfiniBand switches – rose by 27 percent to $170.6 million. We believe its Ethernet business – including chips, boards, switches, cables, and network interface cards attached to Ethernet switches – grew by 53.1 percent to $253.7 million.

Mellanox used to give a pretty good set of details on what generations of InfiniBand were selling at what rates as well as how it was selling switches, chips and boards, and other components like cables and software. But in the wake of the announcement of the Nvidia deal, Mellanox kept mostly mum about this. However, Nvidia did give us a little color in its financial presentation concurrent with the release of its first quarter of fiscal 2021, again ended in April of this year. Take a look:

There are a couple of things that jump out here. First, we never had the breakdown of boards, switches, ASICs, and “cables and other” before. You can see how important it has been for Mellanox to sell the whole shebang with the cable part of the columns on the right being larger than the freestanding ASIC sales that Mellanox does predominantly for a few OEMs and a few hyperscalers and cloud builders who want to use Mellanox ASICs but who want to design and build their own NICs and switches.

We think that Ethernet sales at Mellanox are heavy on the NICs and light on the switches, relatively speaking, but with the Spectrum-2 switches the company started to win some big deals and with Spectrum-3, we think, it is winning a bunch of combo deals with the Connect-X6 Dx dual-port 100 Gb/sec/single port 200 Gb/sec adapters. For at least some of the Magnificent 7 or the Super 8, the combination of Spectrum switching and Connect-X adapters has become akin to InfiniBand for HPC shops and certainly for Nvidia’s own DGX systems – the default networking choice. It looks like switches accounted for around $320 million, or around 24 percent, of sales in 2019 at Mellanox, which came to $1.33 billion, based on this chart above.

This strengthening Mellanox networking business is being added to a strengthening indigenous Nvidia datacenter business, which has grown by expanding its markets from HPC to AI to data analytics and data science and by moving from discrete GPU components to more fully configured system components to switching for memory coherence across many GPUs to fully integrated and manufactured systems that come with containerized HPC, AI, and analytics software stacks on them. At some point, maybe Huang will put on a hard hat and his black vest alternative to his green-ish leather jacket and just offer to build an entire datacenter for customers. Don’t be surprised. . . .

Let’s talk about Nvidia now. In the quarter ended in April, which is the first one of its fiscal 2021, Nvidia had sales of $3.08 billion, up 38.7 percent. Net income was up by a factor of 2.3X to $917 million as both the datacenter and the gaming graphics businesses improved from the very sharp slowdown from the year-ago period.

That net income was 30 percent of revenues, which is the level that the company has been able to hold it at consistently for four quarters. Quite a feat.

In its 10-Q filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, Nvidia did two interesting things. First, it created two new groupings of its products, getting rid of the GPU versus Tegra distinctions it has had for many years and breaking the business down into Graphics versus Compute & Networking so it can slide the Mellanox data into its financials cleanly starting next quarter. The second interesting thing that Nvidia did, in the spirit of better disclosure, was to provide operating income for these two groups. We can capture the Nvidia businesses and their profitability before this convergence happens. It is unclear how automotive is allocated, but presumably those sales and profits (such as they are) are in Compute & Networking and so are the relevant OEM and IP sales where appropriate.

In any event, in the first quarter, Nvidia booked $1.91 billion in Graphics sales, up 24.9 percent, with operating income of $836 million, up 57.1 percent a comprising 43.9 percent of those revenues. Compute & Networking had sales of $1.17 billion, up 69.2 percent with an operating income of $451 million, up by a factor of 4.75X and comprising 38.4 percent of revenues. We think the Ampere A100 GPU accelerators in their various HGX, DGX, and EGX forms have been shipping for months and that is part of the ramp, but according to Huang, the Tesla T4 and V100 accelerators also had a great quarter, and that has more to do with shortages in getting GPU accelerators and demand exceeding supply. Just as happened with the prior Pascal and Volta generations, you will recall.

In the year ago period, most likely because of heavy investments in the development of the Ampere GPU, Compute & Networking sales were only $694 million, and operating income was only $95 million, a mere 13.7 percent of revenues.

Those Compute & Networking sales were a little bit bigger, but not much, than the Datacenter group sales that Nvidia has been giving out covering its fiscal 2015 year to the present, and when its datacenter business was only $57 million in the first quarter of that fiscal year. That business is now precisely – weirdly precisely – 20X larger, and over that same time frame, the FP32 performance for AI training on Tesla GPU accelerators has increased by 33.5X and the raw performance for lower precision math used for AI inference has been boosted by 133.5X from “Pascal” to “Ampere” generations by moving from FP16 floating point to INT4 integer plus all of the advancements such as Tensor Cores and sparse matrix acceleration. FP64 double precision floating point has increased by 4.1X over that same time, including the 2X boost for Tensor Core FP64 just added with Ampere.

Here is the fun bit. In the trailing twelve months of Nvidia’s fiscal year, the Gaming division accounted for $5.8 billion in sales. If you squint your eyes to merge Mellanox and the Nvidia Datacenter division, then together they drive $4.94 billion. And assuming Mellanox had a great April, we can just call it a cool $5 billion. The gaming business, trailing twelve months, is growing at 4 percent. Nvidia’s Datacenter division is growing at 21.8 percent and Mellanox was growing at 27.2 percent, and together they are growing at 23.4 percent. So, unless something really radical happens with either gaming or in the datacenter, this year the Gaming and Compute & Networking divisions should end the year neck-and-neck at around $6 billion each in revenues, and from there on out is anyone’s guess.

Extrapolating is a tricky business, and particularly so given a global pandemic and a medically induced recession as we are all suffering through. Nvidia seems well positioned among a crowd of IT vendors who are not. But nothing is for certain, and you don’t need an AI engine and a machine learning stack to tell you that.

Be the first to comment