The Great Infection is unique among recessions in that it is essentially a self-imposed economic downturn, not the result of over-exuberance or excess optimism or greed, but by a spikey ball of fat that is not alive but is more like a self-replicating biological machine that only knows how to do one thing: Copy itself if it reaches the right sticky environment in time before it dries out and falls apart. You can’t even call that dying because it is not even alive in the strict sense of the word. Maybe we need a new word.

The COVID-19 disease that can result from exposure to the novel coronavirus is horrible and stupid and unnecessary – and absolutely real. It doesn’t matter if you saw it coming or not, because gloating will not save any of us. The most important thing, as we sit in our quarantines, is to protect others by distancing ourselves, get the medical professionals all of the equipment and supplies they need, right now, and keeping whatever cool we have about the economy and our future. So be safe, and stay that way.

In any economy, perception can become the reality, and we were all taken by surprise by the coronavirus outbreak to one degree or another, and our personal and professional lives are all up in the air, all at the same time, and no one knows where the ground is. We believe in the human spirit and the resilience of the cultures of the world, but we also know that something moving so fast can put people into a state of shock. Given all of this uncertainty, it is a lot harder to predict the future, which is something we all want to be able to do with a certain amount of ferocity right now.

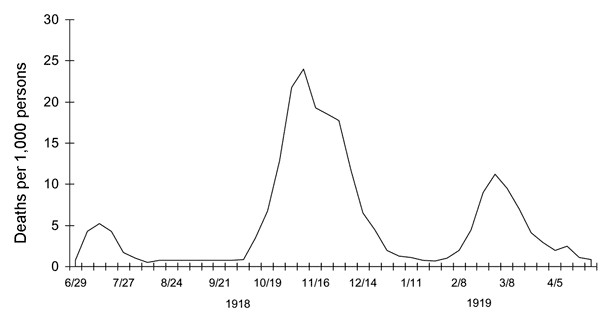

We need to get to the other side of this pandemic so we can fix the damage it has caused to the world and to prepare for what could be a second wave. The second wave was much worse with the H1N1 Spanish flu in the 1918-1919 pandemic, which according to the data we have seen had a little rise in death rates in the early summer of 1918, a huge rise in the fall and winter of 1918 and then another spike bigger than the first in the spring of 1919. Here is the data, courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for weekly influenza and pneumonia deaths from 1918 and 1919 in he United Kingdom that shows the successive waves of the Spanish flu:

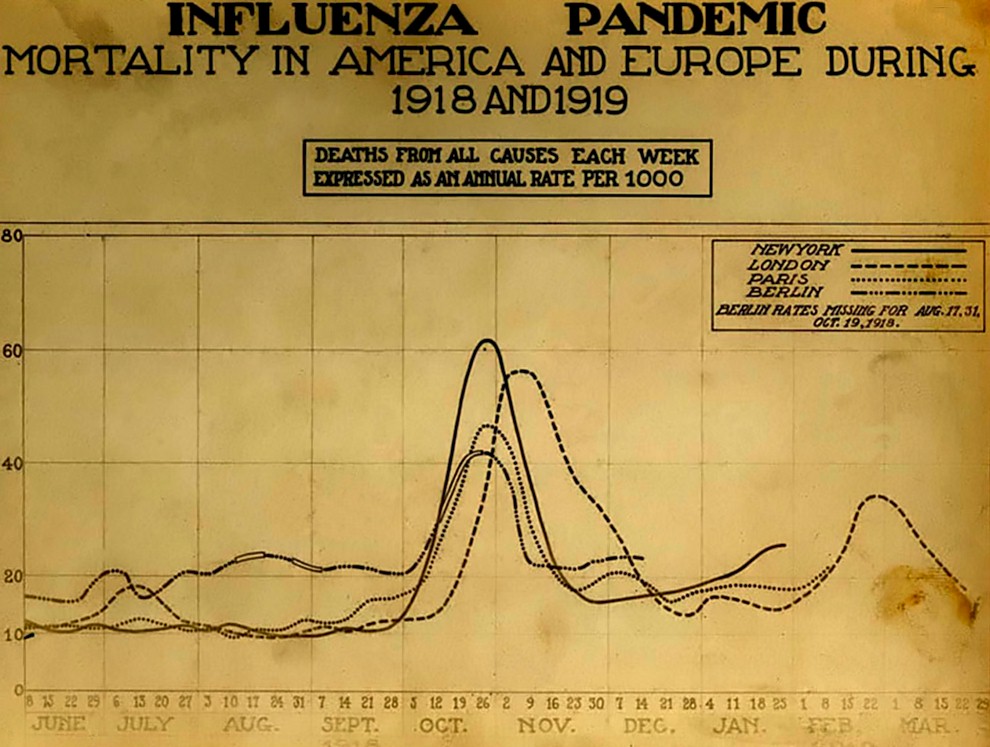

Here is one that shows mortality rates in major cities in the United States and Europe for the Spanish flu pandemic:

The mortality rates in New York, London, Paris, and Berlin were considerably higher, as you see, than across the United Kingdom in general.

Just yesterday, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases within the US National Institutes of Health, said that he is anticipating a second wave because of the highly infectious nature of COVID-19. Michael Levitt, a biophysicist at the Stanford University School of Medicine who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing multiscale models of complex chemical systems, said last week that expected a much less dire result from the coronavirus outbreak in terms of infections and deaths. Predictions are all over the map for how long we will be in quarantine and how many people will get sick and how many will recover.

We all have had an unrelenting torrent of this sobering news, and our job is not to be an echo chamber for this as it is to try to reckon what the effect that the Great Infection will have specifically on the day jobs we all have in IT. Don’t misread that as not caring about the other aspects of our lives; we know what is more import – protecting the homefront – as much as we know what our work is – stimulating ideas on the workfront. We are finding out just how critical some of these services we depend upon, based on massive distributed computing systems, really are to all of us.

As usual, IT spending is a kind of vital statistic for the health of the datacenter ecosystem, and we are starting to see some early predictions and prognostications coming out of the market researchers who track this sort of thing for a living.

Let’s take a look at the early forecasts for IT spending and then drill down from there. By way of comparison, in 2009, the belly of the Great Recession, IT spending worldwide, according to IDC fell by 4.2 percent, from $1.48 trillion to $1.42 trillion, and it grew to almost fill in the gap to get back to $1.47 trillion. This was at a time when the financial services and real estate and car manufacturing businesses were on the ropes and the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 57 percent of its value. It is very, very hard to move such big numbers quickly, even though there were a few quarters in the Great Recession when server sales declined by 25 percent to 35 percent, depending. It was bad, no question about it. But computing is essential to the economy.

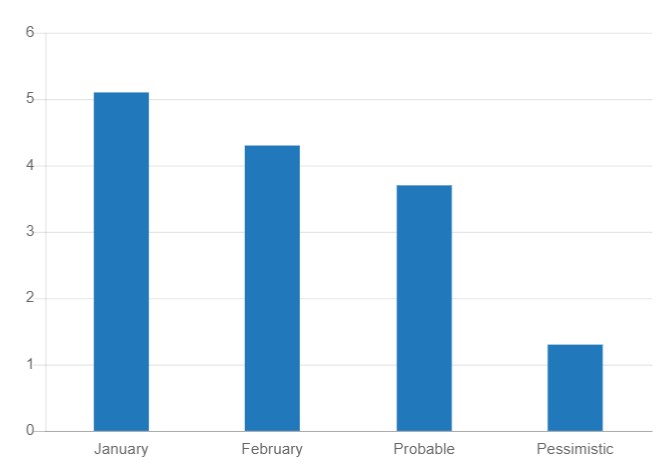

Looking ahead right now, here is how the IDC forecast has been changing as the Great Infection takes hold on more and more of the globe:

Here in March, the range is from a probable growth rate of 3.7 percent to a pessimistic growth rate of 1.3 percent; these figures are based on constant currency across the geographies of the world summed up. Converting to US dollars, as a lot of IT product sales ultimately have done, could change that percentage by a lot up or down depending on the relative strength of the US dollar. The declines were bigger than the constant currency numbers showed during the Great Recession, and we can’t tell what will happen with the US dollar versus other currencies right now.

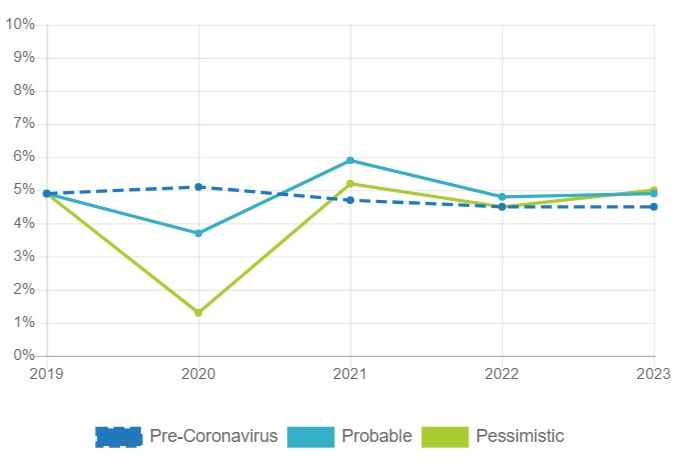

Here is IDC’s forecast before the Great Infection and then the probable and pessimistic scenarios running out to 2023:

IT spending was growing more or less in synch with global gross domestic product, and at a consistently higher rate. This is a valid correlation, we think. If GDP does a nosedive locally or globally, you can expect for IT spending to follow suit, but probably declining at a lower rate because of the necessity of compute, storage, and networking for just about all work in the economies of the world. This following chart shows this all too well:

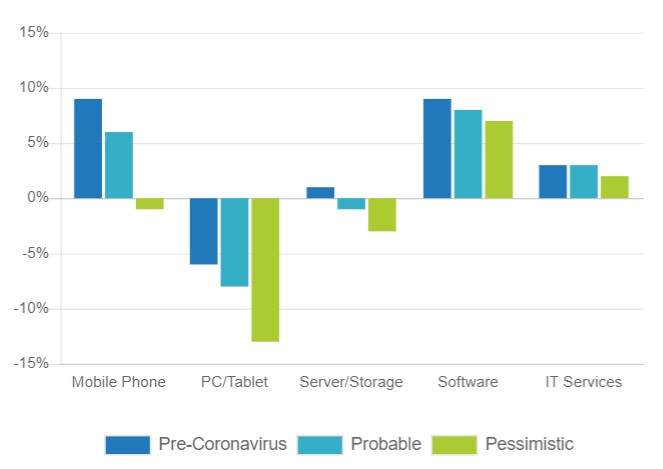

IT software and services are going to be somewhat more resistant to the Great Infection because so much of this is based on monthly subscriptions. PCs and tablet upgrades are completely optional at this point, unless you have to homeschool and can’t share computers with your kids, and servers and storage were not predicted to grow that much this year and they may not take much of a hit in 2020, according to IDC, but there will be a point or two or three of declines according to the current scenarios the company’s economists and analysts have run.

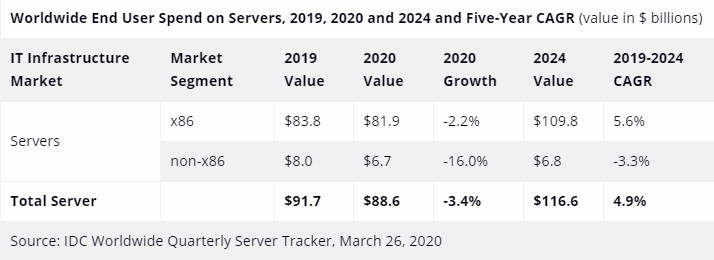

Now, let’s drill down deeper into servers and storage, which we think of as leading indicators for datacenter spending in general (but less so as software is tied less to hardware and more to users). Here is IDC’s server forecast from 2019 through 2024, which was released late last week:

A 3.4 percent decline in overall server spending does not seem a very big hit, although non-X86 iron is going to take a much larger portion of that hit, falling by 16 percent in 2020 to $6.7 billion. It looks like IDC is calling that a floor for non-X86 system sales of just under $7 billion, and that X86 server sales will keep growing on the other side of the Great Infection and break through $100 billion in 2023 and hit nearly $110 billion in 2024.

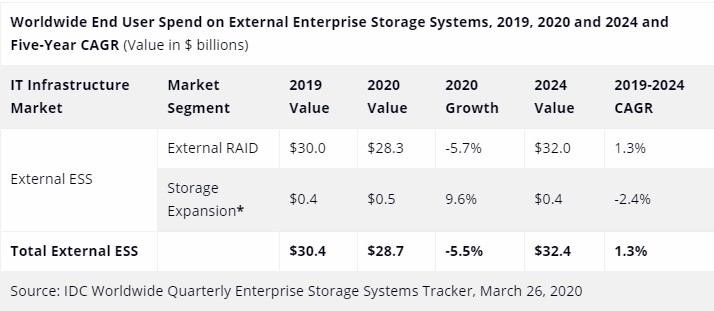

The pressure is going to be on storage, however, according to the IDC forecast:

External enterprise storage will fall by 5.5 percent to $28.7 billion, and eventually crawl its way back with a compound annual growth rate (including that decline in 2020) of 1.3 percent (which means growth rates in 2021 through 2024 will be higher than 1.3 percent). This business was already growing tepidly, and is largely not affected by hyperscaler and cloud builder spending.

Which leads us to a big point. With all of us using more and more services online, the hyperscalers that offer these services or others that do it on the public cloud are going to need to buy a lot more capacity. There is no way they can suddenly stream to a lot of people each day and not build out. This build out could be more than enough to largely offset the spending declines by large enterprises, governments, and educational institutions. We will be watching how this unfolds. But it will be important to realize that this is not going to be an indicator of a move away from on premises datacenters to cloud datacenters so much as an increasing use of services where face-to-face meetings or giant group events were the prevailing way we interacted. If we think another wave of the Great Infection is coming later this year, we could all be right back in our living rooms and bedrooms again, trying to get some work done while watching the kids and homeschooling.

Now, for the HPC market in particular, Addison Snell, of Intersect360 Research, says in an adjustment to HPC spending forecasts in the wake of the pandemic that spending across all HPC products – hardware, software, and services – rose 7.2 percent from $36.1 billion in 2018 to $38.7 billion in 2019, and looking ahead to 2020 before the Great Infection started affecting the economies of the world, the forecast was to grow 7 percent to $41.4 billion. Now, the forecast for HPC spending is to be anywhere from flat to down by 12 percent, so in the range of $38.7 billion to $34.1 billion. Part of the thinking about what looks to us like a rosy projection – which we fervently hope is true – is that investments in supercomputers will be seen as critical against coming up with a vaccine or at least some form of treatment for COVID-19 and what we also assume will be future diseases At the mid-point of a 6 percent loss in revenues for the HPC market in 2020, that would end a ten-year bull run in spending on simulation, modeling, machine learning, and advanced analytics machines.

Be the first to comment