When a company has 500,000 enterprise customers that are paying for perpetual licenses and support on systems software – this is an absolutely enormous base by corporate standards, and a retro licensing model straight from the 1980s and 1990s – what does it do for an encore?

That’s a very good question, and for now the answer for VMware seems to be to sell virtual storage and virtual networking networking to that vast base of virtual compute customers, and take wheelbarrows full of money to the bank on behalf of parent Dell Technologies. Virtualization took root during the Great Recession a decade ago, and VMware, more than any other company, helped drive up the efficiencies on servers and providing that was a rudimentary kind of private cloud. The ESXi hypervisor has been the very cornerstone of VMware, and continues to be, even as the company wraps ever more ornate stuff around it to make it more useful.

We got to thinking about the VMware platform – for after all it is a platform in its own right – as the company was unveiling updates to the vSphere server virtualization stack (ESXi is the dominant component of vSphere, although VMware doesn’t like to use that name much anymore) and the Virtual SAN, or vSAN, virtual storage area network software that runs within ESXi to create VMware’s homegrown hyperconverged storage platform. We got to thinking about how long it has been since VMware talked about the core of the platform in terms of how many ESXi hypervisors are out there and how many virtual machines they have under management, and whether or not that installed base of half a million customers can grow.

The past few years would suggest that this base will not grow, since that 500,000 figure has not changed. But that could be more of a function of the fact that there may not be more than that many enterprise customers who need VMware software. The total IBM systems business never had much more than 500,000 customers at its peak in the late 1990s – about 125,000 using its RS/6000 machines, another 275,000 using its AS/400s, around 10,000 using its mainframes, and another 100,000 using its System x machinery; these numbers are much smaller today, perhaps under 200,000 customers with the selloff of the System x business to Lenovo and the shrinkage in the remainder. Oracle has 430,000 customers using its various operating system, database, middleware, application software. Red Hat has many millions of machines under the management of its Linux distribution, but that is not the same as the number of customers. Ditto for Microsoft and its Windows Server platform, although the Windows Server base, dominated by a huge number of small and medium businesses, has a lot more customers than Red Hat has for Linux. If you are talking about datacenter users, then Windows Server probably inches out Red Hat Enterprise Linux, but if you add up all Linuxes and throw in the cloud builders, hyperscalers, and HPC centers of the world, Linux probably comes out on top. But it is still probably not a number that is larger than 500,000 unique customers for either Linux, all told, or Windows Server, all by its lonesome.

We don’t think there are more than 50,000 unique organizations worldwide that have what we would consider large scale distributed computing in any form – no less than a few hundred nodes working in concert on a job. Many large enterprises have many such distributing computing platforms, mind you.

The funny bit is no one talks about these numbers, and they are kind of important. Back in 2011, VMware said that there were over 1 million virtual machines running in the world, and most of them were atop its ESXi hypervisor, and a new VM popped into existence every six seconds. There were also 1 million VMware administrators in the world at the time, and that was not a very good ratio, when you think about it. But server virtualization on X86 systems was new, so people were still learning. In early 2013, just after Pat Gelsinger, who formerly ran Intel’s datacenter platform business, took over as chief executive officer at VMware and during launch of the company’s “Project Zephyr” vCloud Hybrid Service public cloud, VMware said that it had over 480,000 customers running an estimated 36 million VMs on an unspecified number of ESXi hypervisors. At the time, over 3,700 applications from over 2,000 software vendors were certified to run on ESXi inside VMs with either Windows Server or Linux as their operating systems.

Those figures meant, by the way, that the number of virtual machines from VMware was about the same size as the physical server base; other vendors, of course, have server virtualization on X86 iron and on RISC, Itanium, and proprietary processors, so there were probably on the order of another 30 million to 40 million virtual machines out there in the world, running across maybe 35 million servers. A very large number of these servers, by the way, were not virtualized and run in bare metal mode.

By the summer of 2014, assuming that VM count roughly tracked revenue, we estimated that the VM base for ESXi grew to around 40 million, with somewhere around 2 million to 3 million VMs running on OpenStack clouds, plus maybe another 1 million on the Rackspace Cloud, just for a point of comparison. A year later, when vSAN was finally available at a scale that was suitable for enterprises and not just a toy compute-storage hybrid cluster, we talked to some ex-VMware people and they concurred with our estimate that there were probably on the order of 50 million VMs running on around 6 million servers in the world, numbers that VMware neither confirmed or denied, and when VMware shuttered its vCloud experiment, which we showed it could never afford, and partnered with Amazon Web Services to build public ESXi clouds in October 2016, we said the VM base on ESXi could be around 60 million across millions of servers. (It is hard to say whether or not there has been footprint consolidation, hence our hedge.) Again, VMware was mum about its actual numbers, and this time around, when we were talking to Lee Caswell, vice president of storage and availability products, and Manju Singh, group manager of product marketing for the Cloud Platform business unit, and asked for an update on the ESXi instance and VM base counts, they said they didn’t have those numbers at hand and VMware demurred on updating them for us.

Caswell admits that the numbers we were seeking were important statistics, and we think perhaps more important than the 500,000 customer count we see all the time. vSAN now has over 10,000 customers, and is adding 100 per week, Caswell tells us, which implies that it is going to grow to around 15,000 customers, or at around a 50 percent rate, in the next year. This is one of the fastest-growing products in VMware’s history, to be sure, but given that EMC, VMware’s parent company, sold real SANs to underpin ESXi clusters – and a lot of them because for a long time vMotion VMware teleportation between nodes required SANs – VMware’s enthusiasm for embedding storage on the compute clusters was weak and basically let Nutanix establish the market. Based on the company’s fourth quarter fiscal results ended in early February (VMware is now on the odd-ball Dell fiscal calendar), vSAN license bookings (not reported revenue, but close) grew at a 100 percent rate and hit a $600 million run rate as the fourth quarter came to an end.

If you assume that the storage-laden servers are pretty pricey underneath vSAN – VMware told us a year ago that the software represented only 25 percent of the cost of a vSAN setup – then the vSAN business, all told, is driving around $1.8 billion in hardware and around $2.4 billion in total sales at an annualized rate. This is significantly larger than what Nutanix, which is a little more than half that rate at around $1.2 billion.

While this is all well and good, at this rate it will take until the end of 2023 to convert those 500,000 faithful to also having vSAN. Not all of those customers will opt for vSAN, so the gravy train of vSAN growth might run out sooner and then just scale up as customers add more storage rather than as VMware adds more customers and the storage capacity grows. Nonetheless, this will be a formidable business if even half of that ESXi base commits to using vSAN for storage, driving $15 billion in license revenues for VMware alone by maybe 2026 and another $45 billion in server sales underneath it if current trends persist; about a quarter of that $45 billion in hardware would go to VMware parent Dell. So there’s the win-win.

vSAN was last updated back in April 2017, and we drilled down into the technology with the vSAN 6.6 update, which added native encryption for all-flash or hybrid disk-flash setups, as well as replication across datacenters that implement vSAN in stretched clusters, and tunings in ESXI that offered a 50 percent boost in flash I/O operations per second thanks to the tweaking of the algorithms used for doing de-duplication, checksum, and other functions. These tweaks also resulted in latency reduction on IOPS by 30 percent and 40 percent as well. With vSAN 6.7, which is announced this week, there are other incremental improvements. First, there is a host pinning feature that can be used to tie applications to specific compute and storage hosts in a vSAN cluster; this host pinning works with modern distributed storage systems such as Hadoop, Cassandra/Datastax, MongoDB, and Splunk as well as SAP HANA in-memory databases and Microsoft SQL Server and Oracle relational databases. The fine print on this announcement says it is only available on request, and provided it is approved, VMware will tell companies how to do it. (Apparently, this is a tricky thing.) vSAN also now includes more than fifty health checks that are done in background and that send telemetry back to VMware to help customers do proactive support on their compute-storage hybrids. The software also sports a new HTML5 user interface and a slew of new dashboards to help administrators better do their jobs.

On the ESXi front, there is a new companion to vSAN with the vSphere 6.7 release, which has substantially more performance in the vCenter management console that unlocks the features of the ESXi hypervisor and controls them. The vSphere 6.7 stack hand handle 2X the vCenter operations per second as the prior vSphere 6.5 release two years ago, thanks to a 3X reduction in the memory footprint on the vCenter server. The Distributed Resource Scheduler (DRS) component of vSphere can also crank through its work three times faster over the release two hops ago. This metric is based on a full-scale vSphere cluster, which has a maximum of 2,000 hosts attached to it. VMware is also allowing vCenter to work in a hybrid linked mode that allows companies to manage on-premises ESXi hypervisors and their VMs in the same pane of glass as those running on the VMware service out on the AWS public cloud. VMware is, by the way, now serving ESXi hosts out of the US-East AWS datacenters in addition to the US-West ones in Oregon that the service debuted with.

Singh also hinted that VMware was working to get memory-addressable persistent storage ready to slide into the ESXi hypervisor hierarchy, as you might expect with 3D XPoint memory sticks from Intel and other kinds of memory-class storage (or storage-class memory) providing DRAM-like performance at flash-like prices. Here is the hint:

There is not much there in that reveal. VMware has already put support for 3D XPoint SSDs into the ESXi hypervisor, which was woven in a year ago, but this is a broader architecture that will be able to absorb other kinds of persistent memories when they come to market, including other kinds of ReRAM, as well as PCM, memristor, or whatever things can eventually get commercialized. The idea is that the plumbing in ESXi has been rearranged to make full use of such memories when they do get here. This persistent memory can be exposed as block storage to the guest VM and exposed as byte addressable storage to the guest operating system running inside of that VM. In early tests, presumably with 3D XPoint DIMM sticks, VMware has seen a factor of 6X boost in performance by adding big chunks of this persistent memory to systems, with minimal overhead to the hypervisor or guest operating systems. The idea is to let developers and system architects make tradeoffs between DRAM, persistent memory, flash, and – in increasingly fewer cases – disk storage.

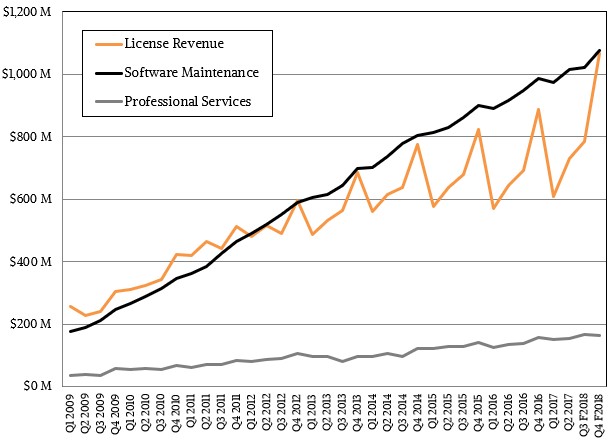

That brings us full circle to the ESXi business. VMware does not break ESXi or vSphere out as a separate product line, VMware said when it went over its fourth quarter of fiscal 2018 financials back in March that compute – meaning ESXi and maybe vSphere – accounted for 35 percent of license bookings, which was down 4 percent year-on-year, but compared against a prior year’s period where compute booking were up 11 percent. This is not the kind of growth that VMware is seeing with vSAN, but it is still a much larger business. The NSX virtual switching line, which VMware got when it acquired Nicira for $1.26 billion nearly six years ago, has over 3,500 customers now and exited the fiscal fourth quarter with a run rate of $1.4 billion, but only 24 percent growth for the period; bookings were up 50 percent for the year, which is probably more representative.

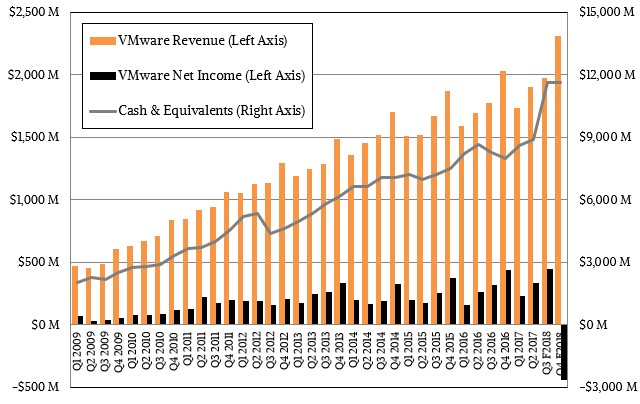

For the fourth quarter of fiscal 2018 year, which ended on February 2, VMware had $2.31 billion in revenues, with 1.07 billion of that coming from licenses; it booked a net loss of $440 million to pay for tax rate and asset changes that were the result of the Trump tax and jobs law signed late last year. For the full year, VMware had $7.92 billion in sales, up 12 percent, and license revenues rose by 14 percent, to $3.2 billion, with a net income of $570 million, half what it brought to the bottom line a year ago. Looking ahead, VMware is expecting 10.8 percent growth in fiscal 2019, up 10.8 percent. This is probably the way it will be for the foreseeable future – and that is appropriate for a mature platform that has addressed its market.

In the long run, which means within the next five years, we think that VMware’s revenues will be representative of how money is spent at a macro level in the datacenter, with perhaps a slightly higher premium coming from compute but storage and networking being bigger than they are now but no more so than the split between compute, storage, and networking in the datacenter at large, with a fourth pillar of management software being a part of the mix. This is where OpenStack, vCloud Suite, vRealize Suite, Cloud Foundation, and so on come in.

VMware’s core compute business will wiggle around here and there, but won’t grow much faster than the revenue streams of the top 50,000 customers who use its platform, which is perhaps a little bit better than global gross domestic product. We think that there will be a wave of ESXi host consolidation – all depending on the price of processors and memory, of course – and that even as the number of VMs presses onwards to maybe 90 million or 100 million in the ESXi pool, the number of hosts could go down a lot. It is reasonable to expect maybe a third of these VMs could end up in the public cloud, again depending on the pricing that VMware and AWS set and the wider availability of the offering. So, the revenue stream from ESXi may not grow much or at all even as the number of VMs under management almost doubles. But vSAN and NSX will go a long way towards filling in that gap, and at the end of those five years, VMware will have created “the 21st century software mainframe” that it set out to build more than a decade ago.

Be the first to comment