Flash memory has become absolutely normal in the datacenter, but that does not mean it is ubiquitous and it most certainly does not mean that all flash arrays, whether homegrown and embedded in servers or purchased as appliances, are created equal. They are not, and you can tell not only from the feeds and speeds, but from the dollars and sense.

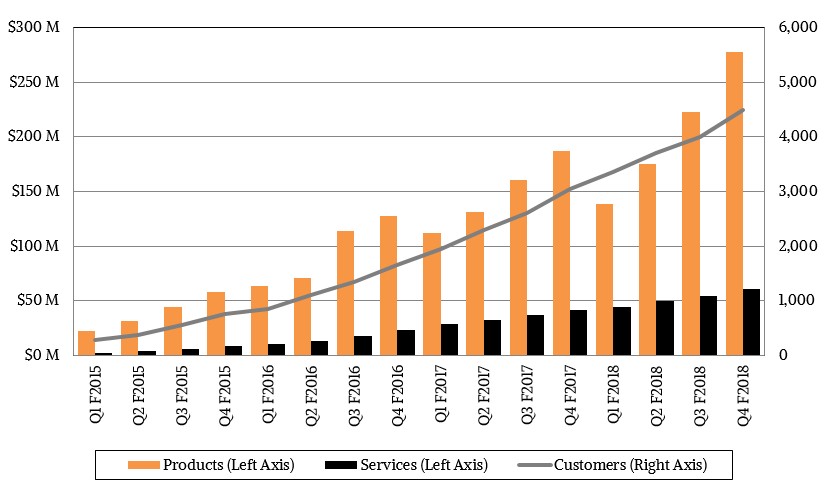

It has been nine years since Pure Storage, one of the original flash array upstarts, was founded and seven years since the company dropped out of stealth with its first generation of FlashArray products. In that relatively short time, the company has ramped up its sales and engineering teams, growing its customer base and widening its product line and addressable markets, and as its fiscal 2018 came to a close in January, it broke through the $1 billion revenue barrier, about a year faster than many predicted it could. The company’s success, with over 4,500 customers – starting in the enterprise, but now branching out into HPC centers and the AI applications of companies of all kinds – is remarkable.

Frankly, there probably has not been a storage company to take off like this since EMC shifted from making DRAM main memory cards for systems in the 1980s to making the extremely well architected Symmetrix block storage arrays based on disk drives, front ended by giant banks of memory and back ended by RAID arrays of cheap disks, in 1990. The Symmetrix was wildly popular on all kinds of platforms, from mainframes to Unix systems, setting EMC up to generate $9 billion in sales a year by the end of the decade.

Pure Storage is not growing as explosively as EMC did back then, but it has beat the pace of NetApp, which innovated in network file storage and also very quickly grew to be a $1 billion company during the early years of the commercial Internet boom.

Here in the 21st century, the Internet is so normal no one even talks about it that way anymore, and the limitations of disk-based storage are inhibiting applications in myriad ways. Hyperscalers and cloud builders, who have exabytes of storage for the services they provide to their millions and sometimes billions of customers, have to make use of disk drives for bulk storage. But smaller enterprises – meaning everyone else in the Global 2000 and anything smaller – don’t have the same storage needs, and an increasing number of them can use all-flash arrays for some or all of their applications. Pure Storage has its venerable FlashArray line for block storage (databases and virtualized server environments) and FlashBlade for unstructured data commonly generated by web applications and consumed by machine learning applications or for more modeling and simulation workloads in the traditional HPC realm.

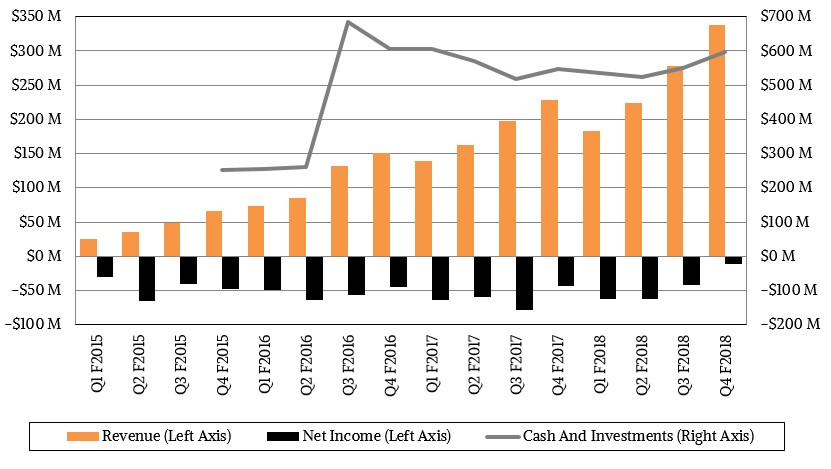

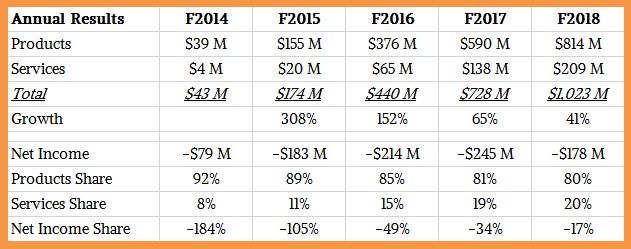

As Pure Storage closed out its fiscal 2018 year, it not only broke through the $1 billion revenue barrier, but it had positive cash flow for the year and, ever so slowly, is making its way to breakeven and profitability. Pure Storage had $530.9 million pumped into it in six rounds of venture funding before it went public in October 2015, when it raised another $450 million from Wall Street with its initial public offering. The venture and IPO money is how Pure Storage could be patient and help the flash market mature in the enterprise, and its engineering – often ahead of the curve of other all-flash array players – means that it is on the cutting edge but not on the bleeding edge where enterprises get nervous. In the past four fiscal years, Pure Storage has booked cumulative losses of $819 million against sales of $2.37 billion, and the initial shareholders have been paid back for those funds (which covered the losses and paid for the hardware and software engineering) with the $3 billion valuation on IPO day, which has grown to $4.55 billion as last week came to a close, an increase of 52 percent in a little more than two years and not a bad return.

Here is the revenue, profit, and cash hoard trend at Pure Storage since fiscal 2015:

And here is the summary of the same information in tabular form:

The next additional $1 billion in revenue stream should be easier to add on top, and presumably if the company can continue to grow at around 30 percent a year going forward – not a bad assumption given the relatively low penetration of all-flash arrays in the datacenter and the $35 billion in total addressable markets that Pure Storage is chasing – then it should break through the $2 billion barrier easily in fiscal 2021. And, at that volume of business, it is hard to imagine that Pure Storage would not be reasonably profitable. The company has consistently gotten around 70 percent of its sales from existing customers, and this is where expanding the product line and use cases has been important. If companies are using FlashArray for block storage and have a positive experience, then it is more likely that they will give FlashBlade a try for unstructured data. The incremental customers added each quarter – somewhere between 350 and 450 new shops, depending on the quarter – expand the base and the rest keep coming back for more.

Pure Storage has made inroads into the Fortune 500, with a third of them buying its gear for one thing or another, which is something all vendors like to brag about because once the big enterprises are doing something, they all want to do it. This certainly happened for EMC, which did not sell servers and which had a very high attach rate on Unix and proprietary systems alike in the early years because EMC repositioned the Symmetrix arrays as the hub for storage area networks with Fibre Channel interconnectivity and support for every operating system under the sun. Symmetrix became the safest, most open choice for high-end block storage, and it created a virtuous cycle. This is something that Pure Storage certainly wants to do with its FlashArray and FlashBlade storage appliances, although it has to do this in a market that is crowded with makers of all-flash wares who want to do the same thing. It remains to be seen if history will repeat itself. But if current trends persist, then by early calendar 2026 (which is fiscal year end 2026) Pure Storage will be as big as EMC was at the tail end of the Unix revolution and the dot-com boom.

That is, unless Cisco Systems takes a shining to Pure Storage and tries to buy it. Since last August, Scott Dietzen, co-founder and long-time chief executive officer at Pure Storage, relinquished his role to become chairman and Pure Storage brought in Charles Giancarlo, who was one of the shakers and movers inside of Cisco for a very long time and who ran many of its key product lines. Giancarlo was a vice president of products at Kalpana, which created the first multiport Ethernet switch, introduced in 1989, as well as the concept of link aggregation; by 1994, Cisco wanted to move more aggressively into switching from its routing base and bought the company for $203.8 million. At the time, Cisco was a $1.2 billion firm with a mere 250,000 units of its gear installed, and most enterprises didn’t know squat about the Internet.

Fast forward nearly three and a half decades, and Cisco has had a server business of its own since March 2009 and now has 65,000 customers worldwide and millions of installed units in the field, mostly at the same enterprises that use Cisco switches. While Cisco has its own hyperconverged storage, thanks to the Springpath acquisition that it did a few years back, what Cisco does not have is its own all-flash array appliances (well, not since buying Whiptail for its Invicta arrays for $415 million back in September 2013 and then quietly mothballing the product two years later.) With EMC and VMware both owned by Dell, they are no longer storage and virtualization Switzerlands, so it was only natural for Cisco to buy Springpath to create its HyperFlex hyperconverged storage (which puts clustered block storage and virtual machines on the same servers in a cluster) and to buy a company like Pure Storage to offer block and object storage running on all-flash media.

Last summer, when Pure Storage had around 3,700 customers, about 1,400 of them were using Cisco UCS server iron, so this is an obvious choice. There have been no rumors of such a deal, but Cisco and Pure Storage are cozy with a partnership that creates converged systems using Cisco Unified Computing System blade and rack servers with built in network interconnects and Pure Storage FlashArray block storage; the compute and networking are highly automated by Cisco and the storage by Pure Storage, and woven together into a single whole. This converged product is called FlashStack.

Cisco would have to do some firewalling, given that Pure Storage currently sells FlashArray and FlashBlade iron only through channel partners. Cisco could not afford to lose that partner revenue stream, at least not for a while.

Cisco does not have to buy Pure Storage to get the benefits of this FlashStack integration, of course. But with $71.5 billion in cash in the bank, Cisco could easily buy Pure Storage and hardly even notice the money missing from its wallet. It is hard to say what Pure Storage would fetch, but it would be significantly higher than the $4.55 billion market capitalization it has now, particularly as Pure Storage is approaching profitability.

Having said all of that, we like that Pure Storage is an independent company and is keen on being an open data platform based on fast flash and whatever non-volatile media might be commercialized. That is in keeping with its name and its founding principles. An acquisition by Cisco would be good for the network and server provider, to be sure, and in a way that Whiptail did not pan out to be. But it might not be good for Pure Storage, unless some other suitor who is not as good of a fit came along.

Be the first to comment