It looks like the push to true cloud computing that many of us have been projecting for such a long time is actually coming to pass, and despite many of the misgivings that many of us have expressed about giving up control of our own datacenters and the applications that run there.

That chip giant Intel is making money as it rolls up its 14 nanometer manufacturing process ramp is not really a surprise. During the second quarter of this year, rival AMD had not yet gotten its “Naples” Epyc X86 server processors into the field, and IBM has pushed out its Power9 launch until early 2018 with the exception of some early adopter customers in the HPC market. The ARM collective, led by Cavium and Qualcomm, is not yet fielding the server-class parts that can take on Intel’s Xeon processors head-on. And so, their field was still fairly open. This will not be the case in the coming quarters, as the Epyc, ThunderX, and Centriq processors get a foot in the glasshouse door; Power9 is more of a wildcard that is expected to play at the high end.

Because of this, Intel could peddle the existing “Broadwell” Xeon E3, E5, and E7 processors and not have to make it up in volume by cutting prices to get customers to buy now rather than wait for the launch of the much-awaited “Skylake” Xeon SP processors, which converge the E5 and E7 lines and which offer more compute capacity and memory and I/O bandwidth, among other things.

All in all, the slight stall ahead of the Skylake Xeon launch was not a big deal, and Intel still managed to ship over 500,000 of the Skylake pre-production chips to some 30 customers as part of their ramp. But, as Intel chief executive officer Brian Krzanich pointed out in his call with Wall Street analysts going over the results for the second quarter, the revenue contribution from the Skylakes was minimal during Q2 – probably on the order of a few hundred million dollars is our guess since Intel has been shipping Skylakes since late last year and all of those 500,000 chips did not have their revenue recognized in Q2. To give you a sense of the relatively small penetration that Skylakes have had, even if they have been shipping quietly since last September to the big hyperscalers and a few HPC centers on the sly, during that time the market consumed around 9.5 million machines, and assuming these are mostly two-socket boxes, that is 19 million CPUs. So the Skylake penetration is on the order of 1.3 percent of the CPU volumes consumed by the market over those four quarters. (September is in the third quarter.) And if you want to be generous and only call it three quarters, it is probably on the order of 7.3 million machines and 14.6 million processors, or 1.7 percent of the server volumes.

These Skylake early adopters presumably paid a premium to get to the front of the line because performance matters a lot to them for internal workloads like running search engines and bragging rights matter to them for their public cloud infrastructure. But then again, these hyperscaler and HPC shops tend to pay a lot less than enterprises for chips – like half as much – so the premium is still less than what enterprises are paying. And this difference, coupled with the move to public cloud infrastructure as well as platform and software services rather than on-premises gear, is really changing the nature of Intel’s Data Center Group business.

The most relevant statistic, and perhaps the most shocking one for some, is that the cloud and communications service provider segments now generate nearly 60 percent of the revenues for Data Center Group. And the most dramatic thing that Intel is now saying is that the decline in enterprise spending, which caught Intel by surprise a few years back and which it thought would reverse course, is now the way things are. Some of this is due, we think, to modest growth for core enterprise workloads, which tend to grow along with gross domestic product, and some of this is due to the shift of applications from internal infrastructure run by companies to public clouds. And let’s be very precise in our language here. When Intel is talking about cloud and comms infrastructure, it is not talking about the style of computing, which is increasingly virtualized and containerized and therefore cloudy, but rather the business model for the delivery of the compute, storage, and networking capacity either as raw infrastructure, an intermediary platform service, or complete applications (aimed at consumers or companies, it makes little difference) run as a service on a hyperscaler or cloud builder or telcos infrastructure. This is a remarkable shift from only a few years ago, when Intel revealed that nearly half of its revenues came from enterprise customers, or two decades ago, when the vast majority did.

“We expect enterprise to continue to decline,” Krzanich put it bluntly. “It declined a bit more in the second quarter than I think we had really projected, at about 11 percent. But if you look at Q1, it declined a little less than we expected, at 3 percent. But we still expect it to decline in those high single digit numbers. Cloud, though, grew greater than we what expected, at 35 percent. We expect it to be in the mid-20s, probably more likely. And then networking and comms, 17 percent, and the adjacencies at 12 percent. So we expect that trend to continue. We don’t need any big shifts in those trends to really get to that high single digit growth rate for the datacenter.”

We were musing recently about what might happen when the server makers of the world could no longer generate appreciable profits from their products, and now we wonder how this will be compounded by the fact that the one profit center they could count on – the pool of millions of enterprises that run their infrastructure inefficiently because they have little choice – starts to dry up, compounding the problem. This is a big issue for the IT industry, because profits fund acquisitions as well as internal research and development investments. But it will not necessarily be a problem for Intel, which will still extract most of the profits for systems for itself, particularly as it delivers memory and flash along with CPUs, motherboards, and networking to the market.

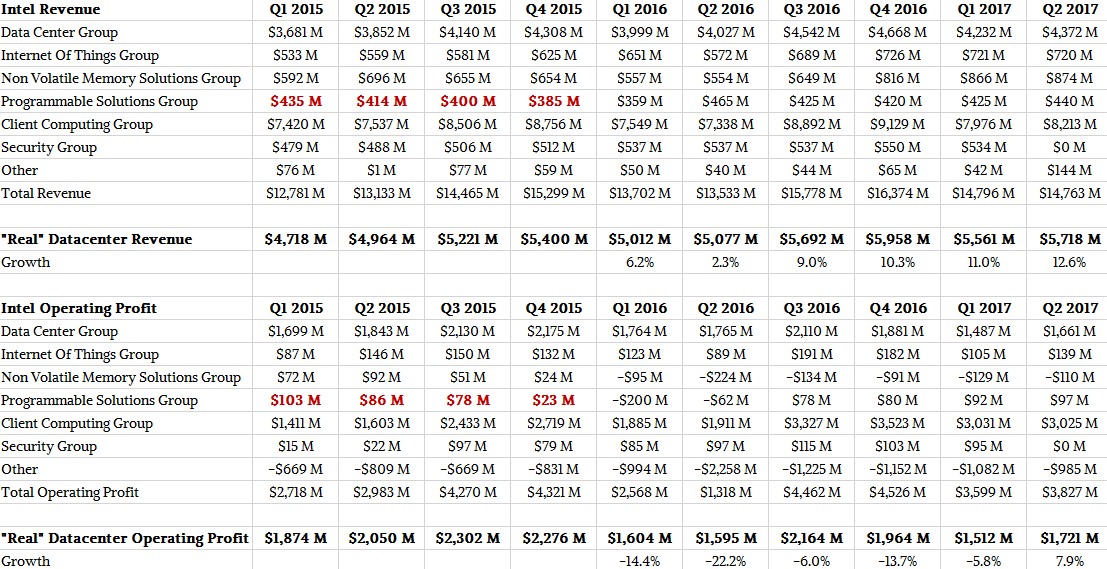

In the June quarter (which technically ended on July 1), Intel’s overall sales were up 9.1 percent to $14.76 billion and thanks to the fact that Intel booked $1.4 billion in restructuring charges in the year ago period, net income rose by 111.3 percent to $2.81 billion. Within this, Data Center Group posted sales of just over $4 billion in core platforms (processors and motherboards), with another $346 million coming from networking and other technologies that Intel peddles. Unit volumes across motherboards, chipsets, and CPUs rose by 7 percent, and average selling prices were up 1 percent thanks in large part to product mix.

All told, this was a 3.3 percent growth sequentially from the first quarter of 2017 and 8.6 percent growth from the year-ago period, which is not bad at all considering the mounting competition that Intel is facing in the datacenter and the fact that it was largely selling last year’s Broadwell products in Q2 of this year.

However, operating income for Data Center Group was under pressure, falling 5.9 percent to $1.66 billion. Part of the reason for this is that the Xeon processors are moving to the front of the manufacturing process line and are shouldering more of the burden of the development costs for 10 nanometer and 7 nanometer efforts, as we explained a few months back, and some of it is due to the fact that the 14 nanometer transition is an expensive one. Data Center Group is also investing more dough into artificial intelligence (both hardware and software) and in other adjacencies such as 3D XPoint memory sticks for servers. Intel says that it is still, with all of these issues, on track for Data Center Group to have growth in the high single digits for all of 2017 with operating margins in excess of 40 percent of revenues. This is a far cry from the 15 percent revenue growth that Intel was projecting only a few years ago, but this is realistic given all of the circumstances. We also think that Data Center Group will come under intense profit pressure as Power, ARM, and X86 clone processors ramp this year and into next, and upstarts Mellanox Technologies, Barefoot Networks, Innovium as well as the incumbents of Cisco Systems, Broadcom, and Hewlett Packard Enterprise get very aggressive with their networking silicon.

The high prices that Intel can charge for flash memory and 3D XPoint used in SSDs and soon for 3D XPoint Optane memory sticks is offsetting some of the enterprise decline – and in fact, the high prices for memory and flash are cutting into the profits of all server makers as well as stalling sales at enterprise shops that are wincing from a bit of sticker shock. The Skylake ramp is hitting the market without the “Apache Pass” 3D XPoint memory sticks that might have mitigated against the shortages in DDR4 and flash memory. But, Intel says it has shipped over 200,000 Optane SSDs to customers so far, and over 50 cloud builders, hyperscalers, and telcos are testing Optane SSDs right now. Moreover, Intel is still promising that the Apache Pass Optane memory sticks will come to market next year, but it is not qualifying that by saying early next year as we expected. (Hmmm.)

Intel is very bullish on the 3D XPoint and flash memory business, which is largely focused on datacenter customers, not consumers, but it does not include the results for the datacenter portion of its Non-Volatile Memory Solutions Group inside of Data Center Group. The memory group had revenues of $874 million, up 58 percent, and operating income shrunk by 51 percent to a $110 million loss from a $224 million loss in the year ago period. The NAND flash business is at breakeven now and the overall storage business is expected to be profitable next year.

The Programmable Solutions Group that peddles FPGA accelerators shrank by 5.4 percent to $440 million, but operating income was almost flat at $97 million. It is going to be a long time before Intel gets its $16.7 billion in bait back on that Altera deal, but Intel is thinking long term about compute and would have had to spend more than that to create its own FPGAs.

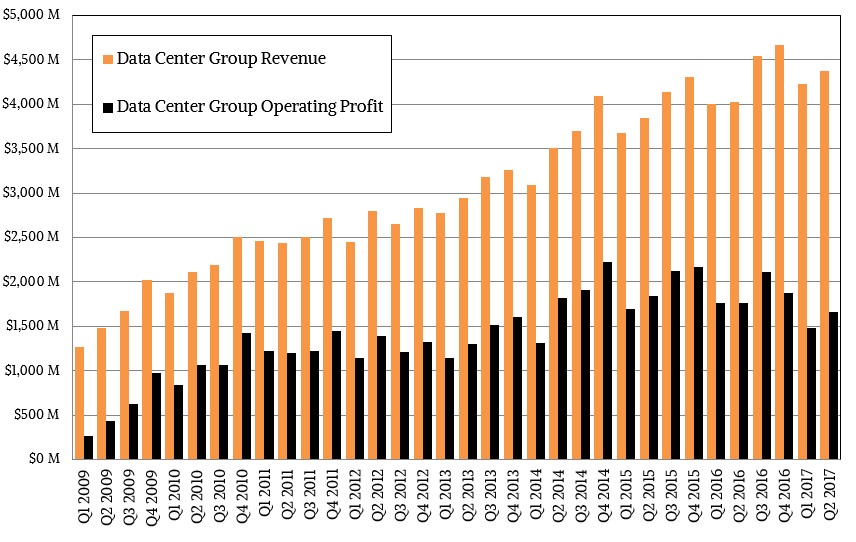

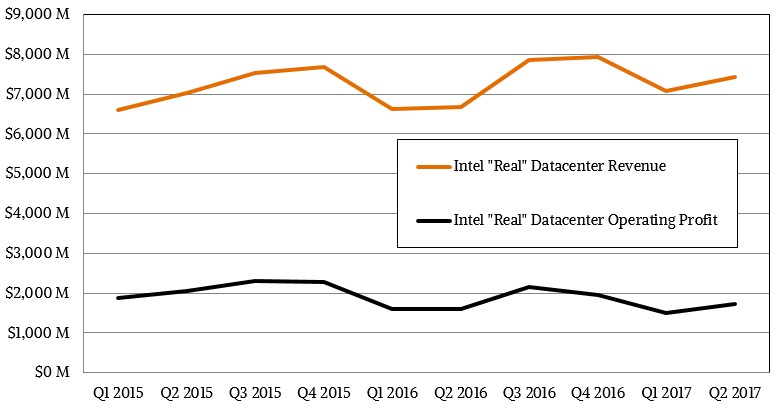

Intel does not report datacenter and client/consumer businesses separately across its groups, and we think it ought to do that. The company’s “real” datacenter business is larger, and less profitable, than it looks if you just take its Data Center Group figures, as best as we can figure, and this is an important thing to know about Intel. Here is what we think Intel’s real datacenter business looks like, in terms of revenues and operating profits:

And here is a table showing the revenues from the Intel groups:

To come up with our estimates of the real Intel datacenter business, we took all of Data Center Group and added in half of the Internet of Things Group and 75 percent of the Non Volatile Memory Solutions Group and 75 percent of the Programmable Solutions Group. We allocated operating income the same way, although the percentages are probably a little higher. Intel has sold off its Security Group, so this no longer contributes to the real datacenter business. If you add it all up, we think the real datacenter business at Intel generated $5.72 billion in revenues in Q2, up 12.6 percent, and its operating income was $1.72 billion, up 7.9 percent.

That may sound like a lot of dough, and it will no doubt get larger as Intel expands out to capture more share in networking and storage and compute needs continue to grow among the cloud, hyperscaler, and telco bases. Intel has its sights set on a much larger chunk of money.

“The datacenter is central to our strategy and is a remarkable opportunity,” Krzanich explained on the call to Wall Street. “By 2021, we expect the datacenter to be a $65 billion silicon opportunity, and we are less than 40 percent of the total available segment today. As we build out the adjacencies like Ethernet, silicon photonics, and 3D XPoint memory, and pull them all together with rack-scale design, we will be positioned to deliver even higher levels of performance and efficiency to our customers and increase our percentage of the total TAM.”

Unless AMD, Cavium, Qualcomm, IBM, and others have something to say about it, of course.

Great Article.

The only points missed were:

– ARM is particularly well suited for some IoT Devices.

– Oracle’s Solaris and Database scale very well and perform exceptionally running on Fujitsu’s SPARC64 M12-2.

https://www.oracle.com/database/index.html

http://www.fujitsu.com/global/products/computing/servers/unix/sparc/

– IBM z14 is ready: http://www-03.ibm.com/systems/z/ and they have the POWER9 (which you did mention).

Intel’s difficult position is that if anyone can prove ‘jumping ship’ is a good idea they’ll have a mutiny on their hands.