Markets are always changing. Sometimes information technology is replaced by a new thing, and sometimes it morphs from one thing to another so gradually that is just becomes computing or networking or storage as we know it. For instance, in the broadest sense, all infrastructure will be cloudy, even if it is bare metal machines or those using containers or heavier server virtualization. In a similar way, in the future all high performance computing may largely be a kind of artificial intelligence, bearing little resemblance to the crunch-heavy simulations we are used to.

It has taken two decades for cloud to start looking normal, and it will very likely take as long for HPC as we know it to morph into AI. But we are not there yet, and HPC as we know it is still an important driver of innovation and therefore vital to the global economy. Moreover, HPC researchers will, we think, be at the forefront of bringing AI into the HPC fold, and in the end it will probably be hard to say for sure if HPC turned into AI or AI turned into HPC.

In the meantime, the health and wealth of the HPC market, which is usually demarcated as for high-scale simulation and modeling workloads with a smattering of more recent analytics workloads, is something we need to keep track of. So much depends on how the organizations of the world spend in this area, which is not about keeping track of money or building and shipping products, but rather changing the nature of the things that are made and sold themselves.

Industry analysts at Intersect360 Research and Hyperion Research (formerly the HPC practice at IDC) both cranked through their financial models and polished up their crystal balls ahead of the International Super Computing conference in Frankfurt, Germany this week and revealed their statistics and prognostications. The two organizations have a slightly different way of characterizing the markets, so their numbers don’t always line up. But the good news is that both sets of numbers characterizing the traditional HPC sector as well as evolving adjacencies are moving up and to the right.

Addison Snell, the CEO at Intersect360, tells The Next Platform that the company has done some fine tuning on its models, and now reckons that the HPC market is larger than it thought, and the biggest increases are coming from software and services that are, quite frankly, harder to count than servers, storage, and switching.

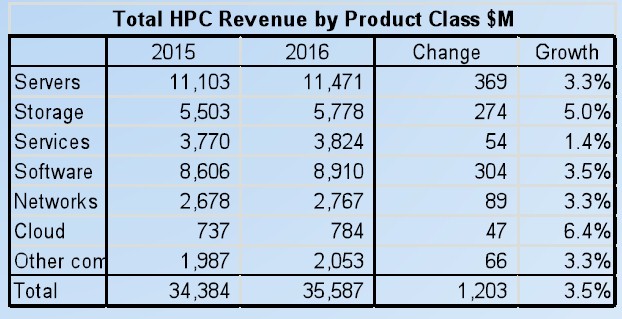

According to Snell, 2016 represented the seventh consecutive year that the HPC market grew, but it looks like the growth in the market has slowed a bit, rising only 3.5 percent in 2016 to reach $35.59 billion in sales across all products and services relating to HPC. Within this overall revenue figure, HPC server revenues rose at 3.3 percent to $11.47 billion, networking rose 3.3 percent to $2.77 billion, and storage rose by 5 percent to $5.79 billion. This is what we all typically consider as the core part of the HPC space. Cloud HPC revenues grew faster at a 6.4 percent rate, but Intersect360 believes that revenues only hit $784 million across all cloud infrastructure makers last year; this is still a nascent part of the market, obviously, and it is not growing at triple digits, as overall cloud was only a few years ago, or even high double digits, as Amazon Web Services is still growing after being in the market for 11 years now. Intersect360 says that HPC software accounted for an astounding $8.91 billion in revenues last year, and rose by 3.5 percent, and that services comprised another $3.82 billion, up only 1.4 percent.

Perhaps the most interesting thing is the market forecast going forward. If you cast back to 2011, Intersect360 says that there was $25.7 billion in HPC spending across all categories in 2011, with industrial companies driving a little more than half of that (52 percent) and academia doing about fifth (19 percent to be precise) and government facilities doing the remaining 29 percent. In 2016, the market had grown to $35.59 billion, as we said, but now industry represents 55.5 percent of the total, or $19.75 billion; HPC spending by governments was $9.22 billion (25.9 percent) and by academia was $6.62 billion (18.6 billion). Ever so slowly, academia and government is representing less of the pie and industry more of it. Looking out to 2021 over this decade long casing of the HPC market, Intersect360 believes that the market will grow a bit faster in the five years, with a compound annual growth rate of 4.3 percent and attaining a level of $43.94 billion in spending. Between 2016 and 2021, the analysts at Intersect360 expect for spending by governments to have an annual growth rate of 2 percent, reaching $10.19 billion by 2021, academia growing by an average of only a tenth of a point to $6.67 billion, and industry growing by 6.5 percent to hit $27.1 billion.

In other words, HPC is going to be more dependent on industry, and vice versa.

Servers will see slightly higher revenue growth over the forecast period, and storage and cloud will continue to be the fastest growing portions of the HPC market. Interestingly, Intersect360 believes that cloud infrastructure revenues will break $1 billion in 2019 and hit $1.21 billion by 2021. This will still only represent 2.8 percent of the overall market, so Intersect360 is not particularly bullish about HPC in the cloud. But remember, this cloudy infrastructure spending represents capacity that is running full tilt, and if an HPC system is only being utilized 25 percent or even 50 percent of the time when it is installed in a private datacenter, the cloud spending is effectively ballooned by the inverse of the cluster utilization of the private machinery. That’s a fancy way of saying that if you ran a cloud as inefficiently as private clusters, it would represent more revenue, or that most of the spending on a private HPC cluster could end up going out the window if it does not have high utilization.

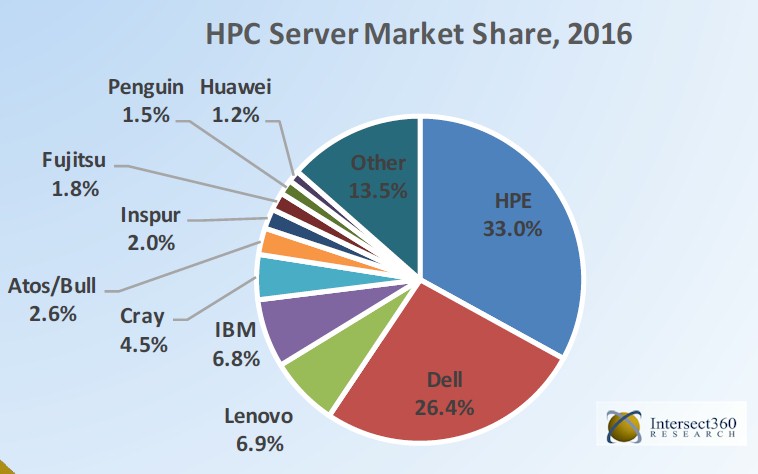

The market models put together by Intersect360 and Hyperion are meant to represent all HPC spending, not just that of the Top 500 systems, so the market shares here look a little different than on the most recent rankings of systems tested using the Linpack parallel Fortran test.

In 2016, Intersect360 figures that Hewlett Packard Enterprise, including sales formerly attributed to SGI, had a 33 percent share of HPC server revenues, with Dell close behind at 26.4 percent of the market. Lenovo got 6.9 percent share, largely thanks to its acquisition of IBM’s System x X86 server business in early 2015, and IBM itself had a 6.8 percent share, much smaller after it sold off that business. Cray pulled in 4.5 percent of total HPC server revenues, with Atos/Bull, Inspur, Fujitsu, Penguin Computing, and Huawei Technology all getting skinnier slices ranging from one to three points, depending. In HPC storage, Dell, thanks to its EMC acquisition, now dominates, with 24.4 percent share, according to Intersect360, followed by NetApp at 15.8 percent, HPE at 13.4 percent, IBM at 9.5 percent, and a slew of familiar names such as DataDirect Networks, Seagate Technology, Spectra, Panasas, Bull, and Fujitsu getting their slices and a bunch of others taking down the remaining 17 percent of the storage pie.

The market for HPC servers and storage is still diverse.

A Second Opinion

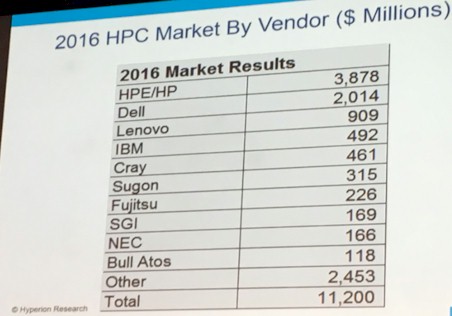

At Hyperion Research, HPC server sales have always been a kind of proxy for the overall HPC market, and Bob Sorensen, vice president of research and technology for the HPC group, said during an ISC2017 presentation this week that the world consumed $11.2 billion in HPC systems last year, which was a record level for HPC server sales since the former IDC started tracking HPC separately from the market at large.

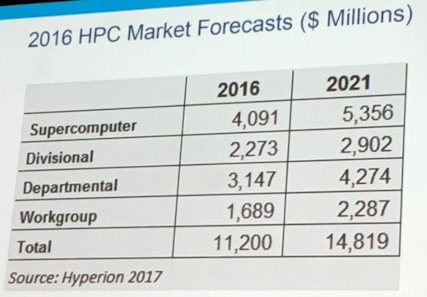

Hyperion breaks down the server sales a bit more granularly into four subsegments: workgroup clusters that cost under $100,000; departmental clusters that cost between $100,000 and $250,000; divisional machines that cost between $250,000 and $500,000; and supercomputers that cost more than $500,000. The HPC server market is a little top heavy, as you might expect, with $4.1 billion in server revenues last year, compared to $2.3 billion for divisional machines, $3.1 billion for departmental machines, and $1.7 billion for workgroup machines. (Personally, we would love to see revenues by compute capacity of the machine or node count or core count, too.) Sorensen said growth in the top end supercomputers was the highest last year, with workgroups showing the next largest bump up.

Here is the breakdown of HPC server sales by vendor according to Hyperion:

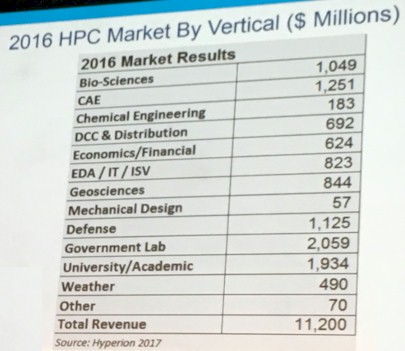

And here is the breakdown by vertical market:

There is some wiggle in there, but the breakdown for vendors is not all that different from that of Intersect360. The vertical market breakdown of HPC server sales is interesting in that it shows how the academic and government organizations that tend to dominate the discussion about HPC do not, in fact, so the bulk of spending on HPC systems. Industrial concerns, as a whole, spend as much as academia, government labs, and defense departments do. To be fair, the government labs and defense installations are often closer to the bleeding edge because, by definition, they have to assume a higher level of risk because it has been left to them to drive the innovation curve.

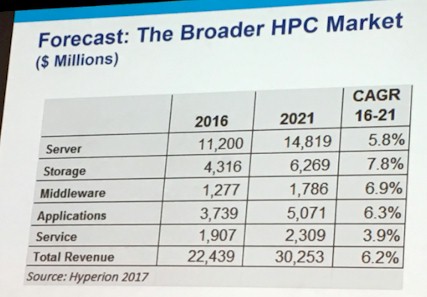

Hyperion is just as bullish about HPC sales looking out into the future as Intersect360, and expects the market to expand by a third between 2016 and 2021, and what is clear from the table about that this growth is not just due to big ticket pre-exascale and exascale systems at the top HPC centers. The growth that Hyperion is projecting is bullish across all classes of machines. It is also pretty bullish across other aspects of the HPC market, including storage, middleware, applications, and services as well as servers. (We presume that IDC lumps networking into servers, since it is not broken out separately. Take a look:

It is immediately obvious that Intersect360 believes that the HPC market is considerably larger than what Hyperion thinks it is, and that comes down, we think, to the fact that people have different opinions about what constitutes HPC and what does not. The good news for people in the HPC community is that the projection is for growth that outpaces that for the economies of the world averaged together and for the markets in servers, storage, and networking across all kinds and styles of computing – with the exception of the hyperscalers and cloud builders.

We like such optimism, but we think so many things are changing between now and 2021 that it is hard to imagine that the definition of HPC as we know it will remain even four years from now. That is how quickly the upper echelons of compute, driven by what we loosely call artificial intelligence, is changing.

Be the first to comment