Every successive processor generation presents its own challenges to all chip makers, and the ramp of 14 nanometer processes that will be used in the future “Skylake” Xeon processors, due in the second half of this year, cut into the operating profits of its Data Center Group in the final quarter of 2016. Intel also apparently had an issue with one of its chip lines – it did not say if it was a Xeon or Xeon Phi, or detail what that issue was – that needed to be fixed and that hurt Data Center Group’s middle line, too.

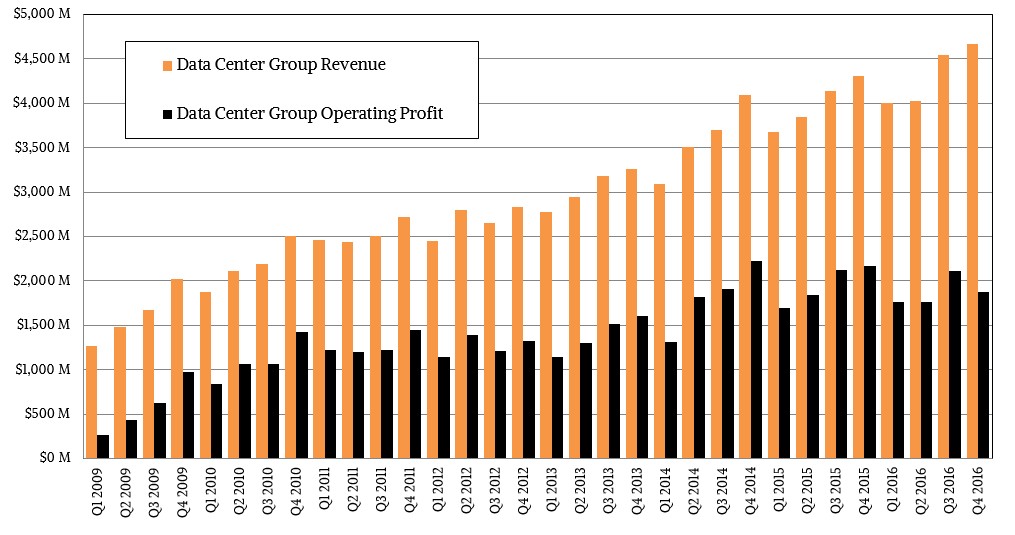

Still, despite a slowdown in spending among enterprises for new compute capacity, Data Center Group still turned in a record year for revenues and profits, thanks to growth in cloud, hyperscaler, telecom, and service provider spending on compute capacity, even if the growth rate was only about half of the 15 percent sustained target rate that the company set for the Data Center Group a few years back.

With Intel having such dominant share of the server market – Xeon and Xeon Phi chips commanded 89.2 percent of server revenues and 99.3 percent of server shipments in the third quarter of 2016 – it is no surprise at all that Intel now rises and falls directly with what is going on among large enterprises, cloud builders, hyperscaler, telcos and other service providers, and small and medium businesses. There just is not that much growth that can come from taking share away from IBM System z mainframe and Power Systems and the remaining bases of Itanium, Sparc, Sparc64, Alpha, and other processors and the ARM server base is still nascent and is no opportunity for Intel to get new sales from.

In the quarter ended in December, Intel’s overall sales were $16.37 billion across all of its product lines, up 9.8 percent from the year-ago period; net income was $3.56 billion, down 1.4 percent. This drop in earnings was not just due to the 14 nanometer ramp with the Skylake Xeons, but also due the ramp of 3D NAND flash memory chips as well as for Optane 3D XPoint memory for SSDs. There were also some costs related to restructuring charges for the layoffs of 15,000 employees that Intel announced last summer as it moved investments away from its Client Computing Group, which makes chips for PCs, laptops, and tablets, and towards new technologies such as 3D NAND flash, 3D XPoint memory, silicon photonics, rack-scale computing, and Omni-Path switching. Intel’s bottom line was squeezed by the ramp of 10 nanometer processes for “Kaby Lake” Core processors, due at the end of this year and their follow-ons, “Cannon Lake,” which will ultimately be re-etched as Xeon server chips, and the work Intel is doing on 7 nanometer chip manufacturing. And finally, Data Center Group’s profits were also impacted by an unspecified intellectual property cross-licensing and patent deal that Intel did in the quarter with an unnamed communications player.

In the final quarter of last year, revenue for platforms at Intel in the Data Center Group – meaning processors, chipsets, motherboards and in some cases systems – came to $4.31 billion, up 7.3 percent, while Other revenue (which is not specified but which should include Omni-Path networking, RackScale architecture, and other stuff) amounted to $362 million, up 23.1 percent. But because of all of these issues above, operating income for Data Center Group fell by 13.5 percent to $1.88 billion.

It is a bit strange that Intel did not announce the intellectual property deal when it happened, but the size of the deal may not have been, in and of itself, material to the company’s financials. As for the chip issue in the Data Center Group, Intel’s chief financial officer, Bob Swan, did not elaborate, except to say that this had a greater impact on the numbers and that there were higher than expected failure rates on unspecified components shipped to some high-end customers and that it had found a fix for the issue and set up a reserve to cover the costs for replacement parts. Neither of these issues, said Swan, would affect the books in 2017.

The big issue for Intel in 2016 was the shift from the 22 nanometer “Haswell” Xeon processors to the 14 nanometer “Broadwell” parts, which provide a bump in performance and price/performance but which also, at least at first, incur higher costs as the manufacturing process ramps.

The real problem is that enterprises, which now account for less than half of the revenues within Data Center Group, are cutting back on spending, and this might be a little disconcerting but it is absolutely predictable given the current global political and economic climate and given that enterprises are moving more and more workloads to public clouds or using services from hyperscalers and cloud builders where they might have otherwise built them and hosted them – and much less efficiently – in their own datacenters. Sales of chippery to cloud builders (which includes what we at The Next Platform call hyperscalers as well as public cloud companies) rose by 24 percent in Q4, according to Swan, and telecommunications and service provider companies both grew at close to 30 percent in the period as well But sales of products that ended up in enterprises or government agencies both fell by 7 percent in the period. The growth on one side is enough to fill in the gap on the other, but it is not enough to keep Intel at that target of 15 percent sustained growth for Data Center Group.

But Brian Krzanich, chief executive officer at Intel, said on the call with Wall Street analysts going over the numbers for Q4 that his team believed that getting back on sustained double-digit growth for Data Center Group was possible over the long haul, even if cloud is, to a certain extent, eating into enterprise.

“We took a look and in 2017 we expect enterprises to be relatively equivalent to what we saw in 2016, which means enterprises will decline,” Krzanich explained. “I think that certainly some of that is moving to the public cloud, and it is moving to those areas at a faster rate. Enterprises have been a little slow in developing private clouds and we are working with several partners like Microsoft Azure around private cloud for enterprises. But if you take a look at the long term we still see this as the growth engine and still getting into that double digit regime. Remember that for us enterprise is now less than 50 percent of the overall datacenter business and that the areas that are growing even faster or as fast as cloud – the network and storage space, where we have very low market share for us and is a great opportunity for us, and the emerging areas like silicon photonics, Omni-Path fabrics, RackScale design, and 3D XPoint – those areas are really what we have always forecasted as the real growth engine for Data Center Group as we exit the back half of the decade. Any time you are going through a market transition, you are not going to get the cloud-enterprise mix perfect, and this is an anomaly right now and we think we have forecasted and adjusted for it correctly. But our long-term growth focused on these areas as we are still confident of this.”

We have always believed that as many millions of businesses start using infrastructure, platform, and software services on public clouds, telcos, and service providers or do certain things with the services that Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, and others offer, that this will remove processing capacity from the dataclosets and datacenters of the world, particularly at SMBs that do not have the desire or ability to do IT infrastructure or software better than what these options are. If a cloud runs at 80 percent efficiency and a corporate datacenter runs at 20 percent or maybe 30 percent if you are lucky, that is a lot of computing capacity that is no longer sold. Growth in such services is masking this decline in sold but largely unused capacity, but at some point, many of the millions of SMBs will just pull the plugs on their servers and give up altogether.

This will have a dramatic effect on the market for server processors, and it is already happening. And it is not as simple as saying that clouds are able to buy huge volumes of stuff from Intel and get pricing that enterprises, through their system suppliers, cannot. Swan conceded on the call that cloud builders (which includes hyperscalers) were indeed able to get lower prices for processors from Intel, on a SKU for SKU basis, but that the cloud builders also tended to buy up the SKU stack and therefore contribute proportionately more revenue than you might guess based on server counts.

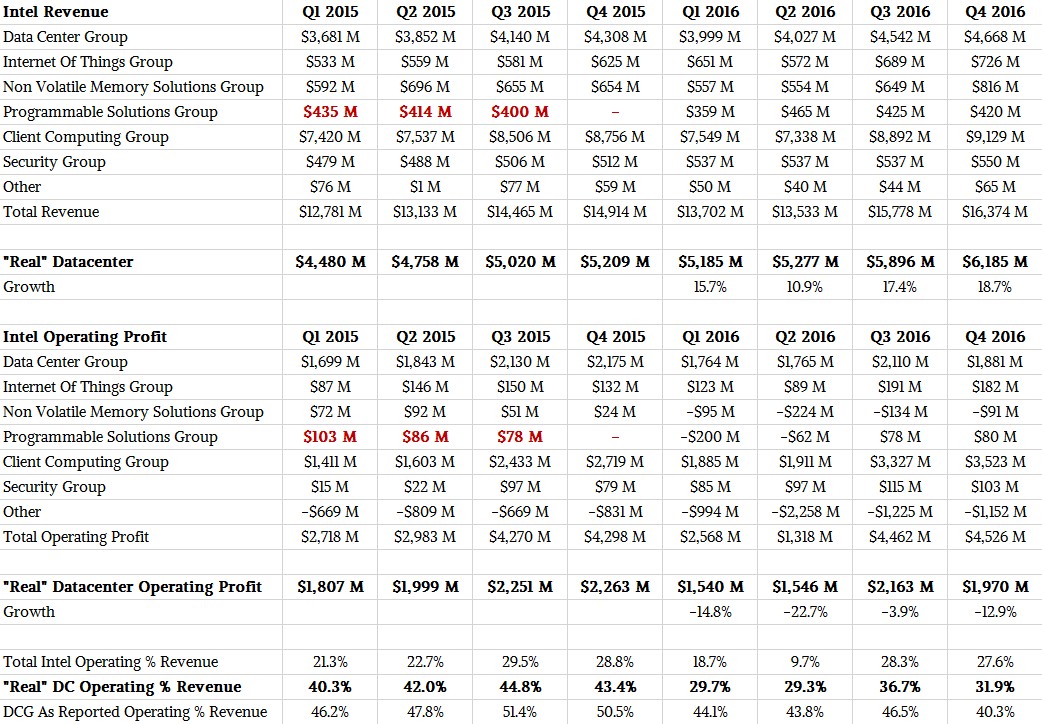

What Intel labels Data Center Group is not, of course, the company’s complete revenue and profit picture in the datacenters of the world. A very large portion of its flash and soon 3D XPoint memory ends up in datacenters, and you could argue that its FPGAs in the Programmable Solutions Group (created in the wake of the acquisition of Altera last year) as well as pieces of its Internet of Things Group and Security Group are also aimed at enterprises, clouds, hyperscalers, and such. Here is our presentation of the revenues and operating profits of Intel’s groups and how we think its “real” datacenter business adds up:

This model above assumes that half of the IoT revenues, 90 percent of memory revenues, and all of FPGA sales at Intel are affiliated with datacenters rather than consumer products. If you add all that up, then Intel’s datacenter business in the fourth quarter came to just under $6.2 billion, and if you allocate operating profits by the same ratio, this business brought just under $2 billion to the middle line. So why doesn’t Intel do its financials this way? You would think that being able to show 18.7 percent revenue growth would be something it would be eager to do, right? Well, with the heavy investments Intel is making in IoT and memory right now, the overall operating profits for this “real” datacenter would be declining in all four quarters of 2016 and, as you can see, the operating profits as a percent of revenue would be anywhere from ten to fifteen points lower, depending on the quarter.

This is all bookkeeping. Intel is shedding people in the PC business and focusing more on the datacenter, and this is what matters to us here at The Next Platform up to and until PC volumes slip so low that the cost of Xeon and Xeon Phi chips start to rise faster than they otherwise might.

Our point is that Intel is investing in its future and that of its vast and diverse customer base, and is facing intense competition on just about every front – especially in 2017. Intel is expecting for a Skylake Xeon bump later this year, despite all of the competition from Power9, Zen Opteron, and several ARM server chips. Krzanich said that Fab 68, where Intel and Micron are building 3D NAND flash and 3D XPoint chips is ramping up and is yielding better than expected, and datacenter-class SSDs in Q4 saw more demand than Intel could supply. Optane 3D XPoint SSDs are expected to ship for revenue in the first quarter, and Optane 3D XPoint DIMM memory sticks are sampling to selected hyperscalers and cloud builders now and are sampling to customers now and will ship in volume in 2018. Intel is modeling for 3D XPoint to be about 10 percent of its memory revenues in 2017 this year, according to Swan.

And as for FPGAs, Intel believes that it gained revenue share in 2016 its main competitor, Xilinx, and believes that as the 14 nanometer Stratix 10 chips ramp this year, it can continue to gain on Xilinx. The plan is to peddle Xeon and Stratix side by side, particularly among network and storage gear makers.

Be the first to comment