While most public cloud infrastructure has full-on server virtualization to dice and slice the compute, memory, and I/O capacity of iron so companies can share it, not every workload runs well atop virtual machines and in those cases, a bare metal cloud is a better place to be.

Rackspace Hosting, which still derives a large portion of its sales from old-fashioned hosting, joined the Open Compute open source hardware effort way back at the beginning of the project five years ago and has taken a measured approach to rolling out Open Compute machinery to underpin its various services, as The Next Platform has discussed recently.

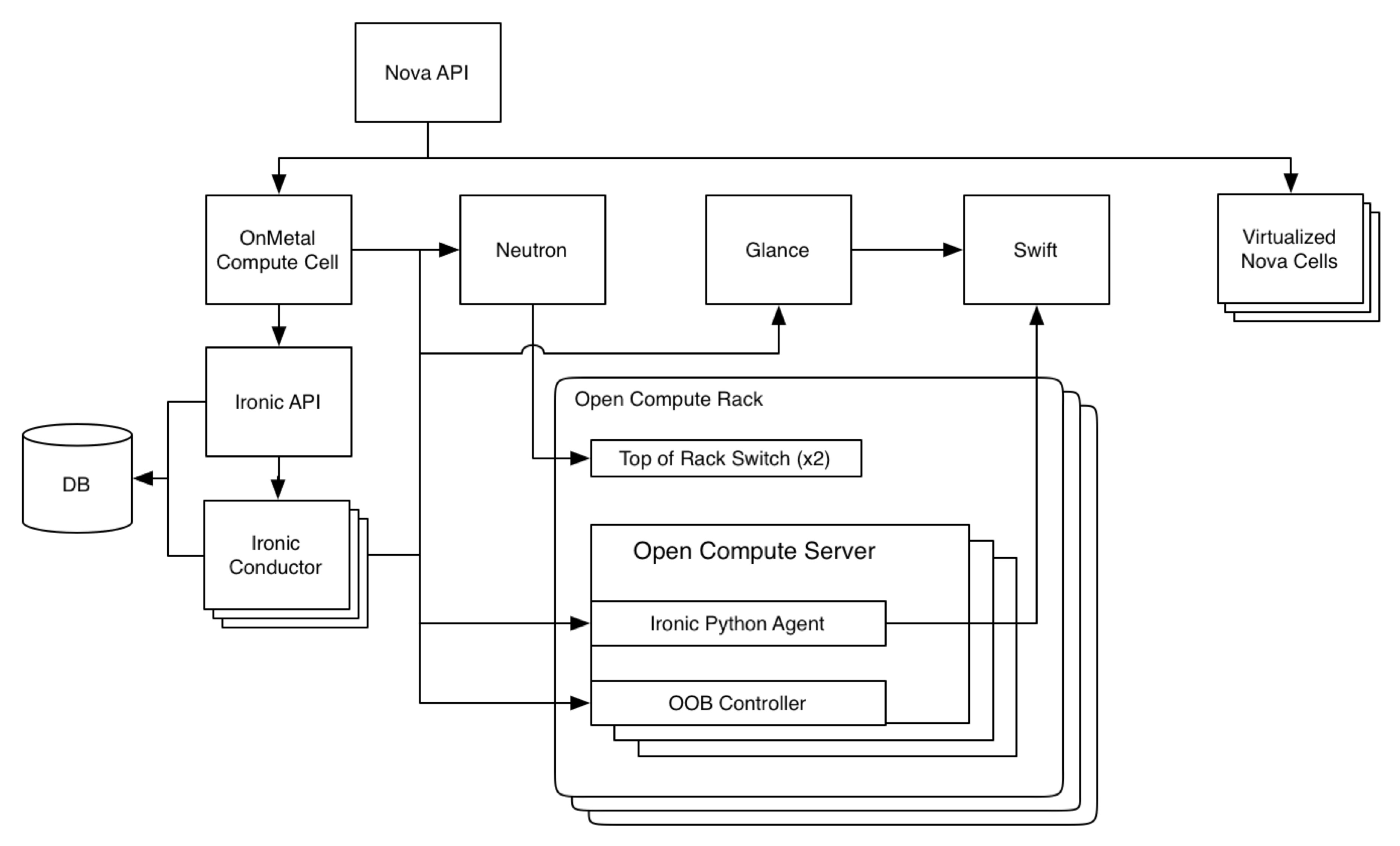

One of the key services at Rackspace to get its own custom OCP iron, which was tweaked by the company specifically for this purpose, is the OnMetal service, which brings the utility-style, metered, instantly on and off style of computing from virtualized clouds to bare metal iron. Rackspace is a founder of the OpenStack cloud controller, and has spent years working on the Ironic bare metal provisioning layer that allows for the configuration of raw servers and the deploying of workloads onto them much as OpenStack provisions hypervisors like KVM, Xen, ESXi, or Hyper-V on top of servers and deploys workloads onto virtual machines running on those hypervisors.

While the OnMetal service is interesting in its own right as something that enterprise customers might want to deploy to run certain applications, the other part of the OnMetal story is the learning that Rackspace has gained in how to configure such machines to support various workloads, and what changes it has made in configuration and pricing in moving from its first generation of OnMetal cloud servers, which debuted in July 2014, and its second generation, which is rolling out right now. The important thing is that if you want to create your own bare metal cloud, you can do exactly what Rackspace is doing, using OpenStack and the exact same Open Compute servers, and see how you might stack up just renting the same iron and getting the company’s “fanatical support.”

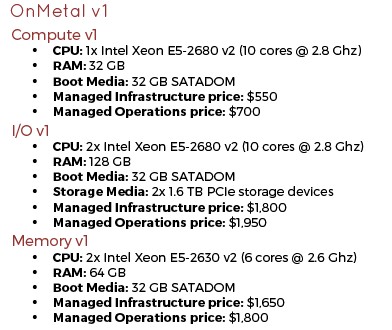

The first generation of OnMetal servers were based on a variant of the “Winterfell” server design from Facebook that Rackspace tweaked to fit into standard 19-inch racks instead of the 21-inch Open Rack employed by Facebook. These Winterfell machines used Intel’s “Ivy Bridge” Xeon E5 v2 processors and were made by original design manufacturer Quanta Computer, Paul Voccio, vice president of software development at Rackspace, tells The Next Platform. Here are the basic feeds and speeds of those machines:

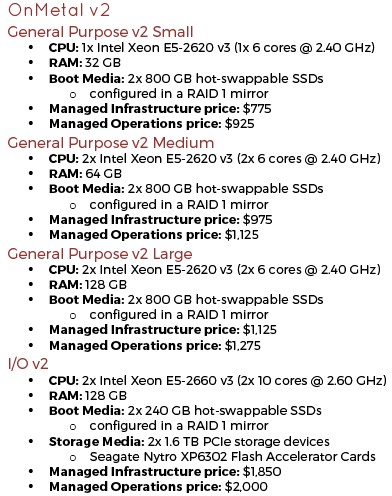

The OnMetal v1 systems were only available in the Rackspace datacenter in Northern Virginia (IAD), but with the expansion of the product with the OnMetal v2 machines, the bare metal cloudy machines are now available in Rackspace’s Dallas/Fort Worth and London facilities. The OnMetal v2 machines are based on the “Leopard” server sleds designed by Facebook (which the social network also uses as it main compute nodes for database, heavy compute, and storage workloads), and Leopard systems from both Quanta and Hewlett-Packard Enterprise have been qualified to run the OnMetal v2 workloads. At the moment, the HPE Cloudline 7100 machines, which are manufactured in partnership with Foxconn, are the ones being installed by Rackspace, constituting a big win for HPE as it battles back against the ODMs. These OnMetal v2 machines are deployed using Intel’s “Haswell” Xeon E5 v3 processors, which were announced in September 2014, not the forthcoming “Broadwell” Xeon E5 v4 processors that are expected soon. Rackspace could not wait for the Broadwell Xeons, which many expected last fall, but the good news is that the Broadwells are socket compatible with the Haswells, so it can change processors at will in the OnMetal v2 iron. Here are the feeds and speeds of the OnMetal v2 systems:

As you can see from looking at the two sets of configurations, Rackspace is configuring the OnMetal machines a bit differently this time around. There are three different general compute systems with varying amounts of flash SSDs plus an I/O heavy machine that has flash SSDs plus Seagate Nytro PCI-Express flash cards to have even higher IOPS. The I/O version is essentially unchanged except that it has more performance inherent in the Haswell chip. The Haswell cores in the I/O heavy variant of the OnMetal v2 servers run 7.1 percent slower than the Ivy Bridge chips in the v1 machines, but the instructions per clock on the Haswells is, on average, about 15.5 percent higher, so there is a net gain of about 7.3 percent on the performance. Which is why Rackspace is charging slightly higher for the v2 machine – $50 per month, to be precise. (The prices shown above are based on minutely billing that Rackspace uses for a 730 hour average month.) The price hike is only 2.8 percent, and the v2 machines also include more local SDD storage to boot (pun intended) than the v1 machines as part of the bargain.

There are some things to note about the OnMetal machines, and it says something about the economics of Intel processors and the other components in use. The first is, learn the lesson of hyperscalers and limit the variation of components in the systems and the number of configurations. There were three OnMetal v1 machines and there are only four OnMetal v2 machines. The second lesson is that workloads deploying on bare metal machines expect to have local storage of reasonable capacity, and that is why Rackspace has added SSDs to the machine for boot media.

The third lesson from Rackspace’s OnMetal setups is to stick with standard processor configurations because they offer the best bang for the buck and the lowest capital outlay in the Intel Xeon line. This runs contrary to what Intel is saying companies are doing, which is buying up the SKU stack, and Facebook also said that it shifted from Xeon E5 machines to Xeon D machines because it was being pushed up the stack for ever-hotter processors to boost the performance of its web software tier, and it compelled Intel to create a 16-core Xeon D precisely because it needed to break that cycle. If companies have been buying up the SKU stack, it looks like some may be backing off as the amount of work per core goes up. In the case of the OnMetal machines, Rackspace has dropped from processors using ten cores running at 2.8 GHz on its compute heavy instance to six cores running at 2.4 GHz.

With this round of v2 iron, Rackspace can add a second processor and extra memory and meet the computing demands customers have, and with the I/O node it can meet the requirements of running NoSQL databases like Redis and MongoDB. The flash on the v2 machines offers 40 percent better read performance and 250 percent better write performance than the v1 machines, and they also have RAID1 mirroring of flash. And because they are bare metal, there is about an 18 percent overhead savings on compute compared to running on virtualized instances using the XenServer hypervisor employed by Rackspace in its own datacenters for its Cloud Servers offering.

Given that Intel sells Haswell Xeon E5-2699 v3 chips with 18 cores running at 2.3 GHz and 45 MB of L3 cache, it is hard to call the six-core Xeon E5-2620 v3 that Rackspace has standardized on for its three different bare metal compute sleds a speed demons. Even though they do run at a slightly higher 2.4 GHz, they have only 15 MB of L3 cache. But here is the thing. At a list price of $417 per chip when bought in 1,000-unit quantities from Intel, the processors that Rackspace has chosen cost a lot less. Intel does not provide pricing for the top-end E5-2699 v3 chip, but we think it is around $3,400. That works out to about 2.8X better price/performance and radically drops the price of a node, too. You have to believe that Rackspace, which has to host a wide variety of workloads on its clouds, has done the math and figured out the configurations that will support the widest number and type of workloads and deliver the best bang for the buck on those workloads.

As for waiting for Broadwell instead of Haswell, Voccio had this to say: “This is not like with HPC customers, where raw processor performance can be a hang up. This is more a situation where processor performance is an important but not critical aspect of the offering where our customers are hung up on a generation of processor. We are not, at this moment, looking to serve HPC customers that are hung up on specific instruction extensions in the latest generations, precise core counts, and stuff like that. These are more typical public cloud workloads.

As for memory scaling, Voccio says that Rackspace tested demand for beefier setups and customers said they didn’t need it yet. But Rackspace is open to the idea, as well as to adding GPU and FPGA accelerators to the machine if needed. At the moment, in terms of networking, 10 Gb/sec seems to be fine for the servers, and if the networking needs to be boosted to 25 Gb/sec or 50 Gb/sec for certain workloads, the Leopard servers use OCP-compliant mezzanine cards and faster adapters can be snapped in.

The OnMetal service currently supports Canonical Ubuntu 14.04, CentOS 6 and 7, and Debian 7 and 8 Linux variants as the operating system on the machines; Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 and 7 are coming later in March and there are no plans to support SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 or 12. Support for Windows Server 2012 R2 is coming in a few weeks, and Voccio says it is possible to backcast to Windows Server 2008 R2 if customers need it and that it will come out with support for Windows Server 2016 when Microsoft ships it later this year. Customers can bring their own licenses or get them under pay-per-use licensing from Rackspace. In the second quarter, Rackspace will link the OnMetal service with its Cloud Networks virtual private networks and RackConnect hooks to lash cloudy servers with hosted servers within the Rackspace datacenters. Bare metal cloud users can already link server instances out to the Cloud Block Storage service, which does just what the name implies.

So who is actually using the OnMetal service? Voccio says that Rackspace saw immediate demand for database workloads (including its own MongoDB service) and has been popular for Cassandra and MongoDB setups that companies deploy on their own. There are also some customers running flash-accelerated relational databases on the bare iron, and the usual real-time analytics based on Hadoop and Spark as you might expect. And finally, there are customers with dynamic web applications that they are writing from scratch to run in container environments like LXC and Docker.

Be the first to comment