Intel had been warning for several months that revenues for its Data Center Group would decelerate a bit as 2015 wound down, and this has indeed happened. But it is not because spending among enterprises, which tend to buy Intel’s chips, chipsets, and motherboards indirectly through OEMs and their channel partners, pulled back further on spending. Rather, spending among the high-end cloud builders and retailers was curtailed.

Sales and operating income in the Data Center Group were, nonetheless, a very bright spot for the company, and did their part for helping the world’s largest chip manufacturer make up for a rapidly declining PC business. Given Intel’s hegemony in the server part of the datacenter, its dominance of compute for storage arrays of all kinds, and its growing influence in networking, the company is a bellwether for datacenter spending overall. Much as IBM used to be, in fact, but has not been for years.

In the quarter ended in December, Intel’s overall revenues were up 1 percent to $14.9 billion, but a 4 percent rise in research, development, and other general spending relating to various processor and memory technologies dinged operating income by 4 percent, which even with a much lower tax rate pushed Intel’s net income down by 1 percent to $3.6 billion. For the full year, Intel posted sales of $55.4 billion, down 1 percent, operating income of $14 billion, down 9 percent, and net income of $11.4 billion, down 2 percent. The company may not be growing revenues and profits, but it is helpful to remember that bringing a fifth of revenues to the bottom line for a manufacturer of physical – and in this case, complex – objects is a very difficult task. (Unless you have the cult status of Apple, which has made it look easy for the past decade.) Data Center Group brings about half of its revenue down to operating income, and that is not only quite impressive, but explains why the proponents of Power and ARM processors are taking on Intel (with limited success so far) in the glass house.

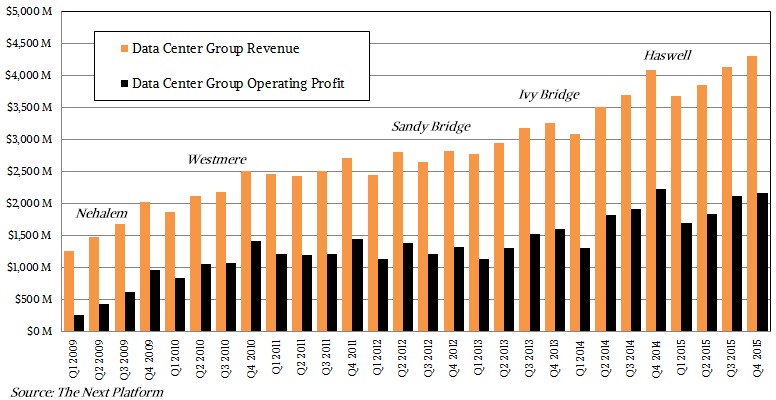

As for Data Center Group, which makes the chips, chipsets, and motherboards that are used in servers, storage, and switches, platform sales came to just a tad bit over $4 billion in the quarter, up 5.2 percent, and other revenues were $287 million, up 7.1 percent. Add it up, Data Center Group had $4.31 billion in revenues for the final quarter of 2015, up 5.3 percent. Operating income for Data Center Group – its profits before corporate overhead and taxes are taken out – fell by 4.3 percent to $2.17 billion. For the full 2015 year, Data Center Group posted just under $16 billion in revenues and brought $7.84 billion to the middle line. That represented 11.1 percent revenue growth and 7.8 percent operating income growth for the year, within the forecast that Intel set a few months ago when spending among enterprise customers took a little downturn given the economic and political uncertainties around the globe.

Intel’s long-term goal in forecasts in past years has been to have at least 15 percent revenue growth in Data Center Group each year, with each quarter rising and falling around that number depending on when Intel launches machines and when its key HPC, hyperscale, and enterprise segments make their big purchases. Since late last year, the forecast for Data Center Group is now for unspecified “double digit” growth, which Intel reiterated this week on a conference call with Wall Street analysts to go over the numbers. Intel is not trying to be vague, but just conceding that it is tough to call with so many changes and transitions going on in the datacenter.

On the call, Intel CEO Brian Krzanich reminded everyone that Q4 2014 was a very tough one for Data Center Group to compare to, with revenues up 25.4 percent in the year-ago period on the first wave of sales of the “Haswell” Xeon E5 v3 processors that launched in September 2014.

“Enterprise was weak in the first half and it has got a little bit more stable in the second half,” Krzanich explained. “What we saw was the normal: the cloud guys turned the slowdown in the fourth quarter because they do not want to be upsetting the cloud infrastructure while the holiday seasons are on people are buying things. And then we continued to see strong growth and strong share gain in the networking and telco side. We are very careful to not look at this on a quarter by quarter basis.”

We happen to think that more than a few hyperscalers, HPC centers, and large enterprises are awaiting the future “Broadwell” Xeon E5 v4 processors, and that might have caught Intel a little by surprise since in past years, there has not been much of a slowdown when there are transitions.

Intel is in the middle of ramping up a cranky 14 nanometer process, which has been used for “Broadwell” and “Skylake” generations of desktop chips and which will be used for Intel’s Broadwell Xeon E5 v4 processors, which Krzanich said would be launched during the first half of 2016.

The scuttlebutt last summer, when it became apparent that Intel was not going to launch the Broadwell Xeon E5s in September, was that we might see them come out in February or March of this year. Intel launched the Broadwell-based Xeon D processors for hyperscalers last March and significantly extended the line in November to blunt the attack of various ARM server chip vendors trying to get their toes in the glass house doors. The Xeon D’s use the 14 nanometer process, too, and in a way, hyperscalers are helping Intel improve its yields with that process before it goes more widely commercial with the full-on Xeon E5s coming out later this year. Xeon E7 processors with the Broadwell cores will no doubt come out this year, too. (We told you a bit about the Broadwell Xeon E5 chips and their Skylake successors back in May.) The 14 nanometer processes have now ramped to be more than half of Intel’s PC chip volumes, which is encouraging for a Broadwell ramp and a Skylake future.

Interestingly, about 40 percent of the chips sold to cloud and hyperscale customers as Intel exited the year were for custom variants of Intel’s server chips, attesting to the value of this proposition to both Intel and its biggest customers. Sales of chips and chipsets into the cloud/hyperscalers and the communication service provider segments were both up more than 20 percent in the fourth quarter.

Intel’s flash memory business grew by 21 percent in all of 2015 to reach $2.6 billion in sales, which is not part of Data Center Group but whose products tend to end up in datacenters.

Together, datacenter, flash, and IoT delivered close to 40 percent of Intel’s revenues and more than 60 percent of its operating margin in 2015.

On the FPGA front, Intel of course closed its $16.7 billion acquisition of Altera at the end of December, after the quarter had finished from an accounting perspective. Altera has not been merged into Data Center Group, but instead is a standalone unit called the Programmable Solutions Group, with Dan McNamara as general manager, reporting directly to Krzanich. Even though this Altera unit does not meet the minimum reporting requirements of the US Securities and Exchange Commission that governs public companies, Intel is going to offer insight into how its business is doing and says it expects about $400 million in revenues per quarter and about $200 million in capital expenses per quarter for the Programmable Solutions Group. The products that this unit kicks out will be integrated with those from both the Data Center Group and the IoT Group.

Altera is a longtime partner, and Intel has been talking about a hybrid Xeon-FPGA processor that fits into a Xeon socket since June 2014, when Data Center Group general manager Diane Bryant showed one off. At the time, the hybrid chip had been in development for a year. The plan became more apparent as Intel bought Altera, with Intel committing to get the hybrid processor out the door by the end of 2016 with a ramp through 2017. Intel also committed to getting a single chip that mixed CPU and FPGA processing on a single die out the door “shortly after that.” Which could mean sampling in 2017 and production in 2018. Intel is also working on a hybrid Atom-FPGA device aimed more at the IoT market.

As it turns out, Intel is going to be able to ship its first hybrid Xeon-FPGA chip in the first quarter of this year, Krzanich revealed – in limited quantities, he said – with that sampling continuing this year and with full production sometime in 2017. Krzanich added that the combined entities are now spending as much on integrated, single die CPU-FPGA hybrids as they are on the packaged hybrids, but did not say when the single die hybrids might see the light of day.

Another nail in AMD’s comeback coffin. As I said if AMD does not over a custom design route in their server chip they are dead. If AMD can not bring a FPGA partner online that will be on same die they are going to be dead.