Even years after the global economies have pulled out of the Great Recession, the pressure is on IT departments the world over to do more with the same budget or less. Just like we have an unshakeable belief that the application of information technology will make life better for businesses and people in their private lives, we now have an expectation that we can get more efficient and less costly IT infrastructure as time progresses.

Whether or not this ultimately proves true is not the point – there are limits to every kind of system in the physical world. The idea that we believe in the elastic consumption of compute, storage, and networking capacity to solve problems is an article of faith. But bringing those efficiencies up and those costs down is a difficult task, and one that cloudy infrastructure aims to address and that all IT vendors are trying to capitalize on to boost their revenues and profits. Aside from Amazon Web Services and its rivals Google, with Compute Engine, and Microsoft, with Azure, it would be hard to find a company that is benefitting from the cloud evolution more than Intel, which as it turns out is selling bullets to all cloud builders and which is a pretty good bellwether, we reckon, for what is going on in the cloud transition.

These transitions take time, of course, and as we have previously reported, Intel is impatient to accelerate the transformation of infrastructure at enterprises from bare metal, isolated silos or plain vanilla virtualized machines to true cloudy infrastructure – with orchestration, automation, and platform layers that make it easier and cheaper for companies to develop and deploy applications. Intel’s Cloud for All initiative wants to help enterprises build the next several tens of thousands of private clouds and however many public clouds the service providers of the world will build, and for good reason: The chip giant already has a lock on the big hyperscalers and public clouds – at least for now, and for the foreseeable future unless the ARM collective and the OpenPower alliance can drive a wedge into the datacenter doors at these massive companies. Oddly enough, it would be easier to sell Power or ARM chips to a hyperscaler that is in total control of its software stack than to enterprises that, generally speaking, are not.

The major transitions in IT, from batch processing to online transaction processing in the 1970s, to client/server in the late 1980s and early 1990s, to web infrastructure in the late 1990s and early 2000s – took many years to cascade down from the largest, most innovative companies to the mainstream. Sometimes more than a decade, sometimes only a few years.

Server virtualization, the precursor to what we used to call utility computing and now call cloud, started out on mainframes in the 1980s (and with clone mainframe maker Amdahl being the innovator, not IBM) and became viable (and necessary) on proprietary and Unix systems in the late 1990s. In all three cases, the machines were so expensive that driving up utilization was absolutely vital for the continuing investment in this type of iron and the applications that ran on them. The X86 server farm (whether it was clustered to run one application tightly or loosely configured for round robin workload sharing) took a while to hit a crisis, but by the early 2000s it was clear that adding more servers was cost effective and server virtualization, driven by VMware and XenSource and eventually Microsoft and Red Hat, took off. But server virtualization only gets you so far and can only drive up efficiency so much, and Intel is much more interested in making it easier to deploy infrastructure at levels far above the CPU in the hardware and software stack.

That’s because Intel believes that if deploying compute, storage, and network capacity is relatively frictionless – moving from virtualized servers farms to clouds, perhaps with containers encapsulating software or perhaps with a mix of bare metal, containers, and virtual machines – then companies will deploy more of that capacity. A lot more, and enough for Intel to keep growing its revenues and profits over the foreseeable future. Intel is also counting on as-yet unknown new applications and companies behind them to bolster its Data Center Group business.

“When we look at the next five years, we actually see that a lot more of cloud is going to be addressing other types of applications, ones that are still pretty nascent right now,” Jason Waxman, the general manager of the Cloud Platforms Group, explained at the recent Data Center Day hosted by Intel for Wall Street analysts. “So even with as much talk as about private cloud, enterprises deploying their own cloud infrastructure, they’re still pretty few and far between, and part of the reason is the complexity of the technology.”

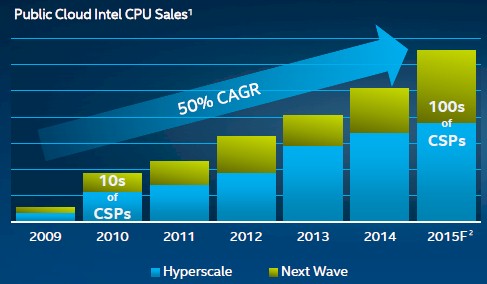

What Intel would love to have happen is for tens of thousands of large enterprises to start behaving like hyperscalers and cloud service providers (as Intel calls them), who have exhibited a stunning 50 percent compound annual growth rate for revenues over the past seven years that Intel has been tracking them. Take a look:

These figures are fascinating, and kudos to Intel for sharing any data at all.

In the data above, the top seven hyperscalers – Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook from the United States and Baidu, Tencent, and Alibaba from China – are the blue portions of the columns, and they have grown their revenues by around a factor of 12X if you do some estimating in the charts, and it looks like the market has expanded from tens of other CSPs in 2010 to hundreds in 2015, and that has driven this portion of Intel’s Data Center Group sales (including processors, chipsets, and other components) by about a 13.5X factor. (These are our estimates.) Over the past three years, Waxman said, the top seven hyperscalers had a compound growth rate of around 25 percent compared to around 42 percent for the other hundreds of CSPs.

Imagine now if Intel can get enterprises to convert to cloudy infrastructure and growth at even a more modest rate than these figures.

“What we are also seeing, and I think this is good for the industry as a whole, is diversification,” Waxman explained. “There are new entrants coming into the market. And in fact, I was pouring through some of my stats last night. The fastest growing one in the green area is growing 8X in terms of their technology deployment year-on-year this year. So there are some real up-and-comers, there is always going to be new innovation in the cycle, and that’s going to continue to drive this cloud growth.”

Digging Into The Data

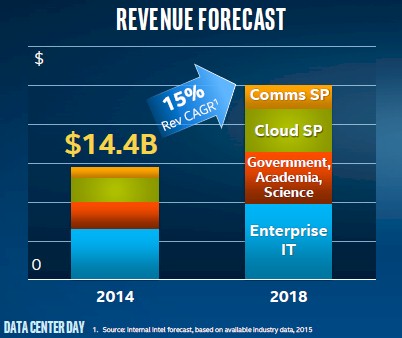

Right now, as Data Center Group general manager Diane Bryant explained at the same meeting, enterprise spending on Intel’s wares is expected to grow at less than 10 percent per year, while sales in the HPC, cloud service provider, and communications service provider segments of its business will grow at more than 20 percent per year.

As things now stand – and we presume assuming that the Cloud for All initiative gets some traction as Intel funds development to make cloudy infrastructure easier to deploy – Intel only expects for enterprise spending to grow from around $6.7 billion in 2014 to just a hair under $10 billion in in 2018. That is an average growth of 10 percent per year between 2014 and 2018.

These cloud companies are early and enthusiastic adopters of Intel technology, and are the main drivers behind the company’s efforts in silicon photonics and are, the company has said in the past, compelling it to spend $16.7 billion to acquire FPGA maker Altera. They are big spenders.

“Our overall share of wallet in terms of silicon footprint into the cloud service provider is about 2X the attach rate versus the rest of the business because they’ve been early adopters for our next-generation technology,” said Waxman, “and we expect to continue to see that. It’s already showing out that they’re also the parties that are interested in FPGAs and then looking at Xeon Phi and other technologies such as silicon photonics as well. So they’re a great test bed and really adopter for us.”

This is one of the phenomena that The Next Platform tracks like a bloodhound.

Intel expects the HPC market (technical computing at government, academic, and research institutions) to drive around $6.6 billion in revenues by 2018, a doubling of its revenues for this category compared to 2014 and representing an average annual growth rate of 19 percent per year by our math over those five years. (Those percentages assume linear and consistent growth over the forecast period, which may not be baked into Intel’s models. We only have a sense of the 2014 and 2018 revenues as presented in a single chart.)

By the end of the forecast period, Intel’s HPC-related revenues from its Data Center Group will be considerably larger than what it gets from the cloud service providers in 2018 – and that is with an expanding definition of HPC to include data analytics as well as modeling and simulation at research centers and with the cloud service providers other than the hyperscalers beefing up their infrastructure.

Here is the interesting bit. If you do the math on the charts that Intel provided, the cloud service provider sector will only see growth of around 14 percent on average per year between 2014 and 2018 inclusive, from around $3.2 billion to $5.4 billion. As the CSP market is expanding, growth is subsiding. As we said all along, there are limits to growth and no market can maintain 50 percent growth rates forever. There are not enough people on Earth to sustain that.

The other interesting bit, if you look at the charts Intel has presented, is that the communications service provider market will be its fastest growing segment, growing at an average of 27 percent per year to rise from $1.2 billion in 2014 to $3.1 billion in 2018. Said another way, three years from now, the communications service provider market will be about as large as HPC and clouds were in 2014.

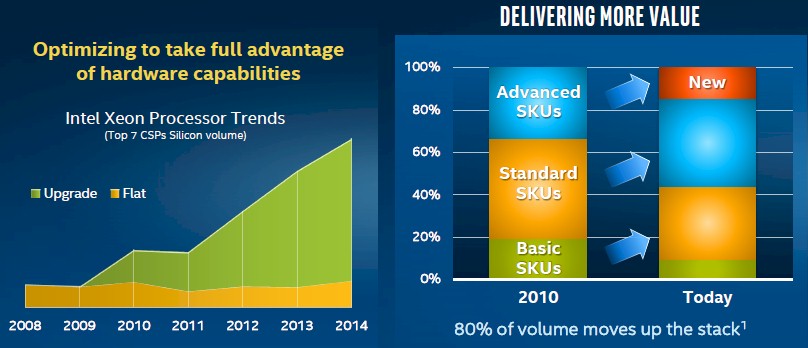

The tremendous growth of services and users for the hyperscalers has been propelling the cloud service provider business at the Data Center Group for the past seven years, and one thing that has helped the revenue stream is that these customers are buying beefier processors with either higher core counts and cache sizes or higher clock speeds – and in some cases, they are getting custom chips specifically suited to their needs. What that chart above shows is that most of the largest hyperscalers are buying processors that provide more oomph, generation to generation, than is provided by a simple Moore’s Law increase, and this is driving up average selling prices and therefore Intel’s revenues among the cloud service providers.

Intel no doubt would like this to happen in the enterprise and communications service provider segments and possibly in the HPC sector. (That market has other issues, and other alternatives such as Intel’s impending “Knights Landing” Xeon Phi processor.)

The question we have to ask is this: What happens if enterprises don’t switch to private and public cloud infrastructure as fast as Intel hopes? We don’t have an answer to that, but it probably means that enterprise spending for Intel’s products returns to growing at the pace of gross domestic product, as it has done for a long time.

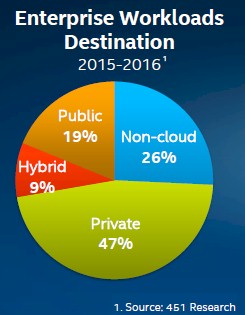

Intel has a broader definition of cloud at work behind all of these numbers, and it means automated, orchestrated, and virtualized compute, I/O, and storage. If you take that as a broad definition, Waxman said that Intel expects anywhere from 65 percent to 85 percent of all workloads running in datacenters (regardless of the segment) to be running on cloudy infrastructure by 2020. Data that Waxman presented by 451 Research showed that about 26 percent of workloads would be deployed on non-cloud systems by 2016, with 47 percent on private clouds, 19 percent on public clouds, and 9 percent on hybrid clouds.

Everyone seems to think this transition from virtualization to cloud will happen, and it does have the feeling of inevitability. But it may take longer than anyone expects in the enterprise, and that is because the cloud software – everything from OpenStack to Kubernetes – doesn’t scale well yet. But a whole lot of smart people are working on these problems, often with the financial and programming assistance of Intel, and these are solvable problems and they will get done.

Be the first to comment