Every major economy that is not the United States or China, which has a disproportionate share of HPC national labs as well as hyperscaler and cloud builder tech titans, wants AI sovereignty a whole lot more than they ever worried about HPC simulation and modeling.

The reason is simple: AI has a direct effect on business and government in that people are either replaced or augmented by AI software and the underlying (and very expensive) hardware that drives it, whereas HPC is an indirect driver of our livelihoods and governance, excepting possibly weather modeling. We don’t think this makes HPC less important – and have said as much over the years – but it is a lot easier to sell the polity and enterprises on billions of dollars of strategic investment in building an AI capability than it is to sell an HPC system upgrade that costs 1/10th or 1/20th of that amount.

This is just the world we live in now, and we have to get used to the idea that AI is the killer HPC app that we have been waiting for. Building machines for AI workloads means that we can get high performance machines that can also run large scale HPC simulations, so that is the good news. The bad news is that HPC applications are going to have to be retrofit with algorithms and solvers that can make use of the tensor math units and varying degrees of floating point precision to get the kind of throughput we expect from a supercomputer that costs a lot more money than HPC centers are used to paying for owing to the high prices that Nvidia and AMD can command for the GPU compute complexes they build.

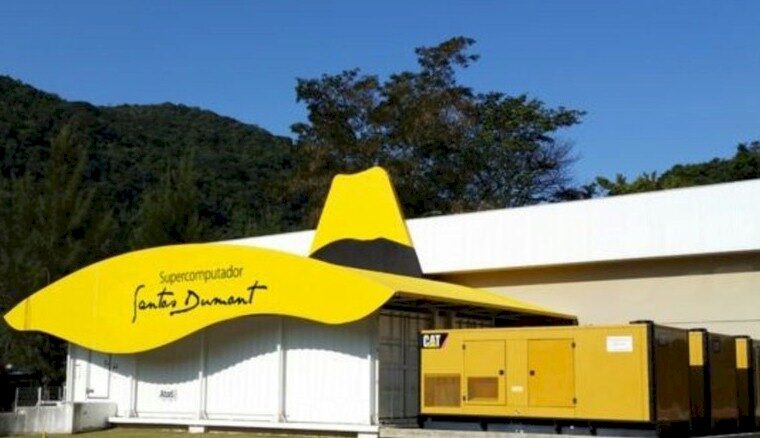

A case in point that we are looking at today is the recent upgrade to the “Santos Dumont” supercomputer, which is run by government of Brazil at the National Laboratory of Scientific Computation (LNCC) in Petrópolis, north of Rio de Janeiro in the state of the same name. This machine, which has been upgraded in the field for the past decade, has just gotten a big tech infusion as part of the Brazilian Artificial Intelligence Plan.

The BPIA was announced in July 2024 and presented to President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva during the opening of the 5th National Conference on Science, Technology and Innovation (5CNCTI) at that time and which was just approved a few weeks ago. The PBIA will invest R$23 billion over the next four years (2025 through 2028, inclusive), which is about $4.2 billion at present conversion rates between the US dollar and the Brazilian real. This is not a particularly large amount of money for a hyperscaler or big cloud builder in the US or China, but it is a lot of money for any government to spend for sovereign AI capacity. Among other things, Brazil wants to have one of the top five supercomputers in the world for running AI – presumably it is not counting the fleets of machines being installed by the hyperscalers, cloud builders, and model builders – as well as having indigenous AI models and not be dependent on foreign sources for models.

Brazil has not choice but to be dependent on foreign hardware, and has Eviden, the HPC division of Atos formerly known as Bull, as its big supplier. Brazil is the largest economy in South America, with a gross domestic product expected to be in the range of $2.13 trillion in 2025 against maybe 215 million people as the year comes to an end.

Last summer, when we were arguing for a massive investment in HPC and AI systems for the United Kingdom, we argued that for traditional HPC systems alone, if you add up the aggregate HPC systems capacity expressed in exaflops of FP64 that is installed in the United States and China and divide by their combined gross domestic products, you get 0.186. If you work that out for Brazil, which is only a little bit smaller than the United Kingdom (GDP of $2.92 trillion in 2024), then Brazil should have just under 400 petaflops of capacity installed across public and private facilities, and if you scale that up to FP8 performance, then you are talking about something around 3.2 exaflops for running both HPC and AI applications.

Sadly for both Eviden and LNCC, the latest upgrade for the Santos Dumont machine, which is named after dirigible, airplane, and helicopter innovator Alberto Santos Dumont, is nowhere near as large as this, but with a $4.2 billion budget and the goal of having one of the world’s top five AI supercomputers, there is always a chance that a future machine will be a biggie.

The initial Santos Dumont machine installed in 2015 had a 1.1 petaflops capacity and cost somewhere between R$50 million to R$60 million. In 2019, this system was upgraded to 1.5 petaflops, and Brazilian oil and gas giant Petrobras foot the bill for the upgrade. This most recent upgrade was announced in March 2024 for a cost of R$100 million ($19.4 million), and boosted the performance of the Santos Dumont machine to 18.85 petaflops at FP64 precision, which is a factor of 6.75X more oomph than the original machine from a decade ago. Once again, Petrobras is forking over the money for the upgrade. It is unclear how much of the machine’s capacity it owns.

The upgrade to the Santos Dumont machine is illustrative in that it has not only a hybrid architecture, but also hedges its bets by using CPUs and GPUs from both Nvidia and AMD. All of the compute plugs into BullSequana XH3000 racks, which are densely packed and which have direct liquid cooling to boost their energy efficiency and to maintain their performance levels.

The upgraded parts of Santos Dumont has five partitions. There are 62 XH3145-H blades in one partition, which each have a pair of “Sapphire Rapids” Xeon 4 processors and four “Hopper” H100 GPU accelerators. The second partition has 20 XH3420 blades, with each blade have three nodes that in turn each have a pair of 96-core AMD “Genoa-X” Epyc 9684X CPUs. The third partition has 36 nodes comprised of four superchips with “Grace” CG100 and Hopper H100 GPUs interlinked with NVLink 4 ports into a shared memory configurations. The fourth part of the new Santos Dumont upgrade has six blades, each with three nodes that are each in turn comprised of a pair of “Antares’ MI300A hybrid CPU-GPU compute engines (the same ones that are used in the “El Capitan” supercomputer at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The fifth partition has four nodes equipped with Grace-Grace superchips.

To our eye, this looks like a testbed for looking at future architectures for a much larger acquisition down the road as well as a hybrid machine that will allow LNCC to do larger HPC and AI work right now than it could do on the prior 1.5 petaflops iteration of Santos Dumont. We can find no evidence that Eviden will be getting an order for a 400 petaflops machine that might cost on the order of $408 million to have Brazil leap to the upper echelons of national lab HPC and AI supercomputing. But such a machine would be less than 1/10th of the $4.2 billion budget for the BPIA effort that has been ratified by the Brazilian government.

We will keep an eye out for such a deal.

Dirigible innovator? lol

Good to see Brazil investing in this HPC and AI upgrade! LNCC’s Santos Dumont is #107 in this year’s June Top500 (Rmax = 14.3 PF/s) and is second in Brazil to Petróleo Brasileiro’s (Petrobras) #86 Pégaso at 19 PF/s. If I calculated correctly, their 7 systems on Top500 add up to a total of 52 PF/s at present.

With its solid system of universities, Venturus, Embraer and many others, I’m sure the country could productively use more petaflops … and a 400 PF/s system sure sounds nice, but even something in the Isambard-AI phase 2 (GH200) and Tuolumne (MI300A) range of 200 PF/s could be sweet imho (with an Eviden design), or even two of them … if such machine(s) can handle the heat of the Brazilian Carnival that is! (eh-eh-eh!)