The so-called “Magnificent 7” or “Super 8” hyperscalers and cloud builders of the world may comprise a substantial slice of worldwide sales of servers, storage, and networking, and the cloud capacity and hyperscale services they provide may in turn represent a significant – but nowhere near dominant – chunk of overall IT spending. But if you really want to know what is going on with the tens of thousands of IT shops at large enterprises on Earth, you need to study the remaining original equipment manufacturers, or OEMs, who sell the vast majority datacenter gear into these shops.

One of the central premises behind the founding of The Next Platform is that technologies developed for HPC and hyperscale systems eventually trickle down into enterprise datacenters. But in most cases, that trickle down is not done by the original design manufacturers, or ODMs, that co-design custom machines for hyperscalers and cloud builders and then manufacture it at high volume and low margin for these upper echelon customers. Rather, the OEMs, some of whom have ODM-like operations for the next tier down of webscale operators and telcos and other kinds of service providers who have hundreds of thousands of servers and buy in lots of 10,000s of machines, do the innovating and the manufacturing and try to average that technology out so it is appealing to the tens of thousands of large enterprises. This gear is not usually as barebones as the gear sold into the hyperscalers and cloud builders, and often because the server is still the unit of resiliency in the enterprise. Enterprises are still, in many cases, managing lots of diverse pets instead of herds of genetically identical cattle. That’s just the way it is.

The two biggest OEMs in the world for servers and storage, of course, are Dell Technologies and Hewlett Packard Enterprise, which is why we like to keep tabs on what they are up to and how they are doing financially. Inspur, Lenovo, and Cisco Systems are also important OEMs in the enterprise datacenter, but they are not yet anywhere near the scale of Dell or HPE. That said, we will start covering them a little more closely going forward because they really are important OEMs. But today, we are talking about Dell and HPE, who both just released their most recent quarterly financial results and who both have a non-standard, non-calendar financial year.

Despite all of its efforts in acquiring Compaq (and through it Tandem and Digital Equipment) as well as Silicon Graphics and most recently Cray, HPE’s datacenter hardware business is smaller than Dell’s so we are going to talk about Dell first. Which, for the moment at least, still has control of the VMware software and services business, too. But that is changing, too, as we discussed recently, with Dell (the company) getting ready to spin off VMware into a separate company and Dell (the man) being the biggest beneficiary of that spinoff thanks to a $10 billion special dividend to Dell shareholders. With so many pre-exascale and exascale supercomputer wins being taken down by HPE (thanks to the Cray acquisition), there is an outside chance that as these machines are accepted that HPE could once again catch Dell or even surpass it when it comes to the top line. But as you will see in a moment, neither company is profiting all that much from their respective datacenter businesses. Not like they hope to, for sure, but maybe all that is realistically feasible for OEMs in the 21st Century. Both are improving their situations in recent months and years, so there is that.

One big difference between Dell and HPE, of course is that Dell has help onto its PC business while spinning off its services and software businesses while Hewlett Package split itself into two, putting servers software, services, and switching into one company (HPE) and PCs and printers into another (HP Inc, which is a pun given the fact that this part of the old HP makes most of its profits from printer ink). HPE, like Dell, has been spinning off services and software to get down to the core datacenter hardware business. Neither has a very big datacenter switching or routing business, by the way. They both roll it into servers to protect the small. Both companies have reasonably large break-fix services and support businesses relating to their hardware platforms.

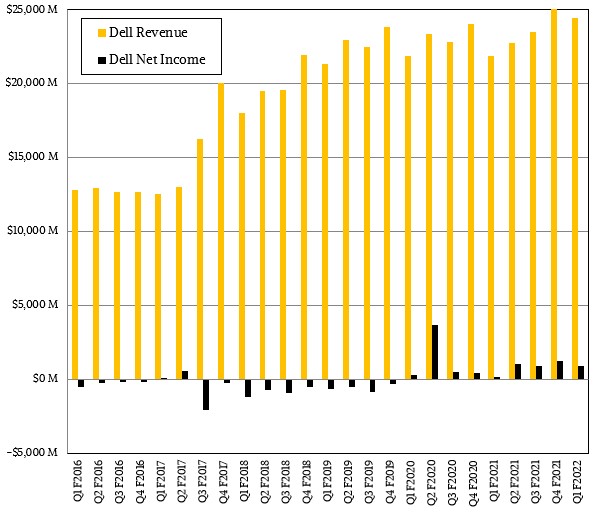

In the quarter ended in April, which is the first quarter of the company’s fiscal 2022 year, Dell posted sales of $24.49 billion, up 11.8 percent, and net income more than sextupled to $887 million, which is roughly on par with prior quarters even if it was many times higher than the $143 million profit Dell had in Q1 fiscal 2021. That profit represented 3.6 percent of revenues, which is a little lower than where Dell has been averaging in the trailing twelve months. The point is, as you can see from the chart above, you can see a whole lot more black ink in recent quarters than Dell has been throwing off in the past, although when it spins off VMware that is going to change, bigtime.

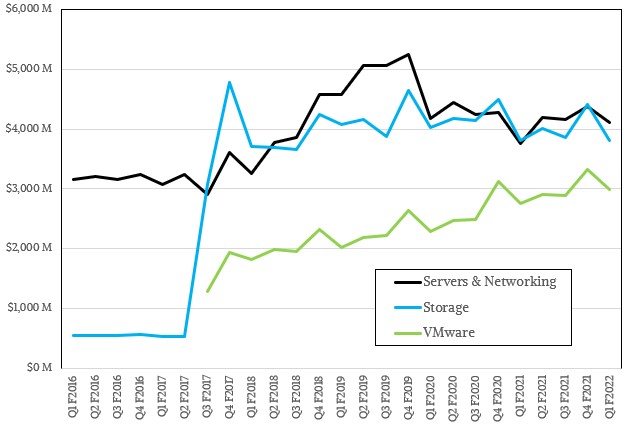

During the April quarter, Dell’s servers and networking business had $4.11 billion in revenues, up 9.3 percent, and storage sales fell by two-tenths of a point to $3.8 billion, resulting in the Infrastructure Services Group at Dell having a combined $7.91 billion in sales, up 4.5 percent. Interestingly, operating income for Infrastructure Services Group rose by 7.7 percent to $788 million, which at 10 percent of revenues is a tad light compared to the average per quarter for the past several years for Dell’s datacenter business. Dell’s financial reports did not provide much insight, except to say PowerEdge orders were up 7 percent and midrange storage orders were up 23 percent in the quarter. VxRail hyperconverged storage and PowerStore midrange storage, in fact, both grew at 23 percent.

Jeff Clarke, vice chairman and chief operating officer at Dell, said on the call with Wall Street analysts that Dell’s total addressable market is increasing from $150 billion in 2019 to $200 billion by 2025, and said Infrastructure Services Group was “driven by an improving demand environment for compute and building momentum in storage” and that Dell believed “demand will continue to improve as we move through the year as customers accelerate their IT investments with focus on hybrid cloud solutions.”

As for supply chain issues, which many IT suppliers are complaining about on their quarterly calls, Dell showed the benefit of being the biggest and therefore at the front of the line.

“We really haven’t seen significant supply constraint in the server space at this point,” said Tom Sweet, Dell’s chief financial officer. “Obviously, some of the input costs are going up around DRAM and NAND. But in terms of our ability to meet demand, we’ve been able to navigate through that. And our lead times in servers are generally on standard lead times. So the ISG environment to date has been relatively unaffected by some of the supply chain constraints as we look at it today.”

By the way, Dell’s Client Services Group, which we don’t really care about here at The Next Platform except for the volume buying leverage it gives Dell, had $13.31 billion in sales in fiscal Q1 (up 19.8 percent) and operating income rose by a very healthy84.1 percent to $1.09 billion. But even with that, the operating income for the Client Services Group was only 8.2 percent of revenue and therefore not as strong as that of the Infrastructure Services Group.

VMware, for its part, turned in the third best quarter in the company’s history, with $2.99 billion in sales, up 8.6 percent, and operating income of $841 million, up 8.8 percent and representing 28.1 percent of revenues for VMware. Again, that was a little lighter on the operating income than the historical trend, but still a very respectable level indeed but not surprising given the 300,000 enterprise customers using the ESXi hypervisor and vSphere virtualization management stack as their core platform for managing and slicing up infrastructure into something that is cloud-like.

Take a good look at that chart above. Ask yourself this: Why would Dell really want to spin off VMware? The business grows almost algorithmically steadily and will within the year be about the same size as its server and storage businesses, and way more profitable. Having spent $67 billion to acquire EMC and VMware, you would think the last thing that Dell, the man, would do is sell off VMware. But remember, Michael Dell is VMware’s largest shareholder, and he is going to personally get the biggest piece of that special dividend to shareholders. The smart thing might be to tell Wall Street to stuff it and ride this gravy train up and then back down, but for whatever reason, Michael Dell wants his money now. Perhaps that says more about what might be peak VMware – and when it might be happening – than anything we can project with our Excel spreadsheets.

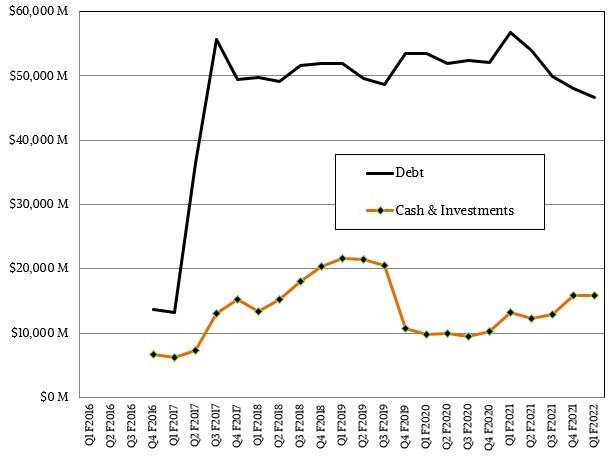

The debt load at Dell, the company, could be part of the reason Dell, the man, wants to sell VMware. It is substantial, as you can see:

Dell exited the quarter with $15.91 billion in cash and investments, which is a pretty decent hoard, but it still owes $46.68 billion dollars in debt to various venture capitalists and banks that were part of the $25 billion deal to take Dell private and the $67 billion deal wot buy EMC and VMware. If you have to sell off the pieces to pay down the debts, did all of this maneuvering really get Dell, the company, anywhere? It certainly made headlines and made Dell a bigger IT supplier, and maybe that is what this is really all about at this point. Dell is the biggest OEM, the biggest server supplier, and the biggest PC supplier. That is worth something, and it is arguable that it could not have gotten there without doing these big deals.

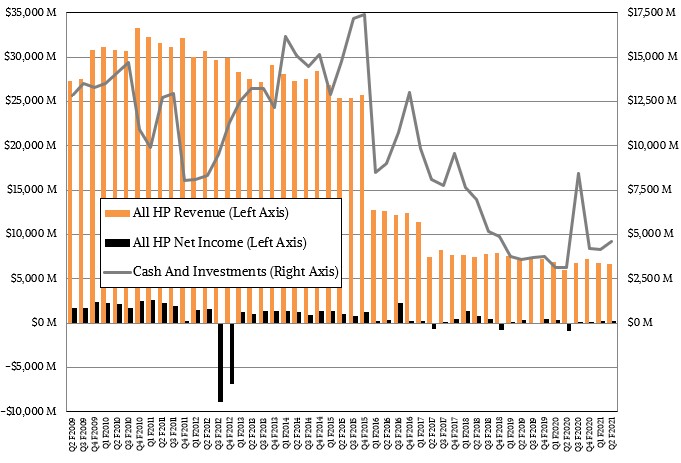

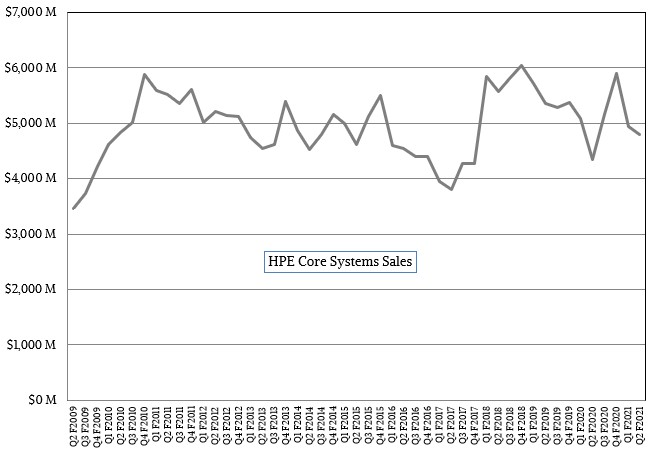

Over at HPE, there is only datacenter (and a little edge) revenues, which are obviously a lot smaller than when Hewlett-Packard was trying to create an alternative to IBM two decades ago. The fall has been pretty high through divestitures, and what is really left is basically Compaq plus Cray minus PCs and printers:

HPE’s revenues were up 12.1 percent year on year, and the company shifted from an $821 million loss in the year ago period to a $259 million net income this time around, so relatively new HPE chief executive officer Antonio Neri must be quite pleased with himself indeed. The company exited the quarter with $4.63 million in cash.

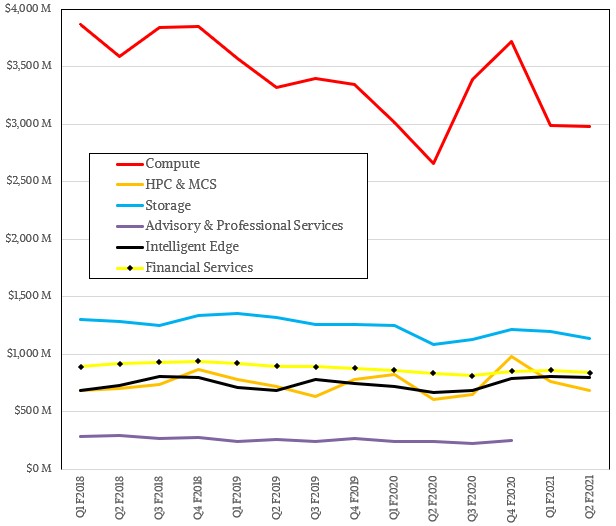

Two years ago, after Neri took over, HPE recategorized its financials, which are presented graphically here:

The compute business, which includes the mainstream ProLiant systems as well as a smattering of Cloudline machines still sold to some webscale (but not hyperscale) customers, had $2.98 billion in sales, up 12.1 percent year on year, but against a very easy compare and not anywhere near the historical levels that HPE has enjoyed with its core X86 server lineup. As you can see from the chart. Some of this is due to competition from Dell, but some is also due to the rise of Inspur in Asia, which is growing like crazy, and some of it is due to enterprises stretching out their capacity during the coronavirus pandemic, and some of it is due to the cloud comprising a bigger share of enterprise compute than it did several years ago. This core datacenter compute business did, however, book $335 million in operating income, more than double against its own weak compare in the year ago period. That operating income represented 11.3 percent of revenues for core servers.

The HPC and Mission Critical Systems division, which sells big NUMA systems and HPC clusters based on Cray, SGI, and HPE designs, had $685 million in sales, up 12.9 percent, and brought a mere $19 million to the middle line for operating income, a mere 2.8 percent of revenues. As we have contended in the past, it is very, very difficult to make a buck in the HPC business, and this just proves the point. IT vendors who make supercomputers make their money democratizing those technologies to the enterprise. If you can’t do that, you don’t profit as much as you might. But that could change as this business gets larger.

“We are the undisputed market leader with an industry leading portfolio in AI and deep learning solutions for the new age of insight,” Neri proclaimed on a call with Wall Street analysts. “We continue to execute on over $2 billion in awarded contracts and we are pursuing a robust pipeline of another $5 billion in market opportunity over the next three years.”

That is a pretty big business, and one HPE could not chase without Cray, and Cray could not chase without HPE – or someone as large as HPE, at least. IBM has deep enough pockets to play the HPC game right and could have bought Cray, and Dell could have done it, too.

In any event, Neri reminded Wall Street of the inherent lumpiness of the HPC business, in part to the unpredictable lead times between when a supercomputer is ordered and when it is accepted by the customer and therefore they pay the bill and in part due to the timing of core component launches from chip suppliers. Neri reiterated that HPOE expected this HPC & MCS division to deliver 8 percent to 12 percent revenue growth this year, and was on track to do so two quarters in. (We wonder what will happen to revenue projections of HPC shops decide they want their Cray supercomputers under a GreenLake pricing scheme. . . . )

The overall HPE storage business, which includes its share of acquisitions (3PAR, Nimble Storage, SimpliVity, LeftHand Networks, and others) as well as homegrown products, posted $1.14 billion in sales in its April quarter, which is its second quarter of fiscal 2021. Operating income, however, for storage came to $191 million, or 16.8 percent of sales. This is a much better level than core compute or HPC is doing for HPE.

Add it all up, the HPE datacenter compute, storage, and networking business had just a hair under $4.8 billion in sales, up 10.3 percent, with operating income of $545 million, up 46.5 percent. Dell’s equivalent Infrastructure Services Group was, to remind you, $7.91 billion in sales, up 4.5 percent, with an operating income of $788 million. HPE’s datacenter business is 60 percent the size of Dell’s and in this quarter at least a tiny bit more profitable per dollar generated.

This article should have been much more explicit about giving Michael Dell credit where credit is clearly due for building a small supercomputer business at Dell from scratch, without spending 1.4 billion to acquire a supercomputer firm like HPE did.