It is a good thing for Nvidia that most of the hyperscalers in the world – or at least the ones that matter – also have substantial public cloud businesses. While the hyperscalers can do anything they want to run their own applications, on any hardware that they want to buy or create, the cloud builders have to find the most generic compute that they can and try to get it to do as many kinds of legacy and new workloads as they can. And because of that, even those hyperscalers and cloud builders who are most proud of their own compute engines still have to buy a mega-buttload of Nvidia GPU accelerators to support HPC, AI, virtual desktop, video streaming, and rendering workloads.

We expounded upon this idea in The New General and New Purpose In Computing back in June 2020, and what we said back then is holding true in Nvidia’s financial results for the first quarter of its fiscal 2022 year, which ended in April and which the company went over with Wall Street today.

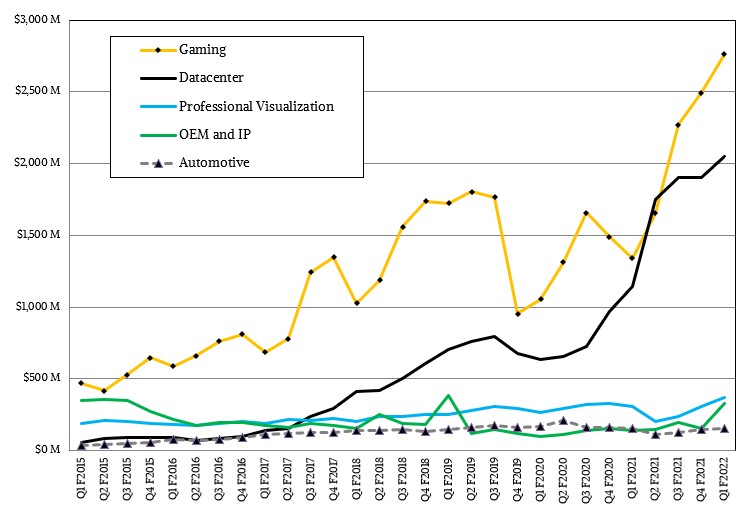

The company is hitting on all important cylinders, setting all-time records for sales of gear aimed at gaming, datacenter, and professional visualization, and is getting yet another boost from a new wave of cryptocurrency mining to boot.

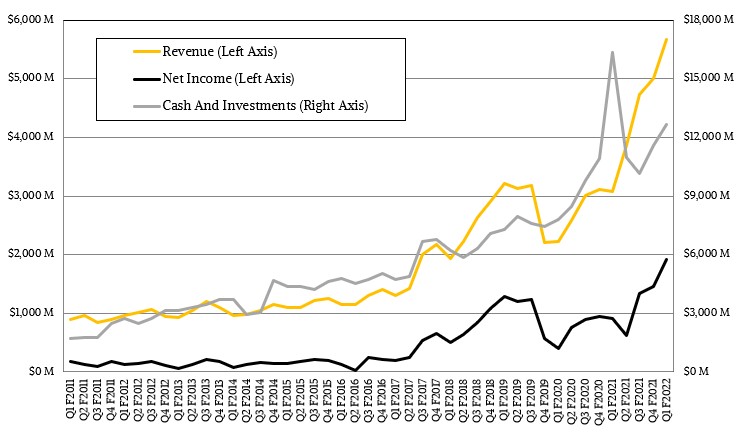

In the April quarter, which technically ended on May 2, Nvidia’s sales skyrocketed by 61.1 percent top $5.66 billion, and net income almost kept pace, rising 53.4 percent to $1.91 billion. That net income is a very respectable 34 percent of revenues, which is the kind of bottom line you expect to see from a very good software company, not a company that largely sells GPUs for gamers and professionals and GPU accelerators for datacenters, plus a smattering of software and services here and there. Every quarter that goes by, with Nvidia raking it in like this, makes that $40 billion acquisition of Arm Holdings all that much cheaper, and as the April quarter ended, the Nvidia kitty was at a very tidy $12.7 billion. By the time the Arm deal might close in early 2022, as Simona Jankowski, vice president of investor relations said the company was on track to do as planned, Nvidia will have as much money (or more) as it had in the bank when it paid $6.9 billion in cash to acquire Mellanox Technologies for its network ASIC, switch, and adapter businesses and the fledgling DPU business that is becoming the third pillar of Nvidia’s datacenter strategy.

The first quarter of fiscal 2022 marks the first time that the datacenter business actually broke through $2 billion in sales. In fiscal 2018, Nvidia was kissing $2 billion in datacenter revenues annually. At the moment, Nvidia’s datacenter business has a run rate that is about one third of that of Intel and IBM, which have true systems businesses on the order of $24 billion a year.

That datacenter business, as you can see from the chart above, had a flat spot in fiscal 2020, which hyperscalers and cloud builders were digesting the GPUs they had already acquired and when companies were waiting to see the next generation of “Ampere” GPUs and what they might hold. But aside from that, the datacenter business has grown at a high double digit rates or triple digit rates, and if this trend persists – especially as DPU products start to sell, enterprises adopt AI and HPC technologies (mimicking the hyperscalers and cloud builders), and networking and CPU compute start to ramp, somewhere around fiscal 2025 or so Nvidia could have a datacenter business that is as big as Intel’s is now and probably much bigger than IBM’s will be at that time, even with Red Hat helping it expand up the stack and away from its dependence on the venerable mainframe.

If you don’t find this remarkable, you are not drinking enough coffee, or whisky, or both.

Nvidia has to do a lot before this can happen, of course, including fending off competitors who want to steal its machine learning lunch and kick its HPC books out of its hands. But thus far, Nvidia is the safe bet for the general purpose accelerator, and we think all kinds of options are going to present themselves with the BlueField DPUs, the Grace CPU, and InfiniBand and Ethernet networking. And a lot of that will have to do with the trickle down of architectures from the hyperscalers and cloud builders to regular enterprises who cannot – or will not – host their AI and HPC applications in the public cloud, even if they will create and test their AI and HPC applications – and the workflows that increasingly link them – in the public cloud.

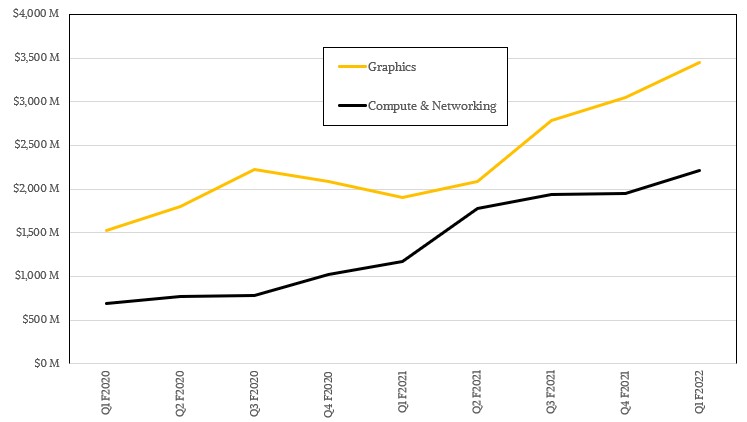

The Datacenter division had sales of $2.05 billion, up 96.6 percent year on year, while Professional Visualization was down 7.3 percent to $372 million. Both we up sequentially, as was the Gaming division, which drove $2.76 billion in revenues, up 67.3 percent year on year.

Jensen Huang, co-founder and chief executive officer at Nvidia, said on the call with Wall Street going over the numbers that demand for Nvidia’s datacenter products was strong “straight across the board” and that “demand was strengthening.” The networking business that Nvidia got through the Mellanox acquisition was up year-on-year and sequentially, but the company has stopped talking about how much revenue this represents within the Datacenter division. The cloud builders and hyperscalers led the growth, with adoption of A100 accelerators and HGX and DGX platforms, and all the major clouds have rolled these out for HPC and AI training workloads. Nvidia is seeing greater traction in selling various of its GPU accelerators as inference engines, too, and the company said that it was not just limited to the T4 units launched two years ago, but also including the top-end A100 accelerators as well as the new A10 and A30 accelerators that are tuned to offer better bang for the buck for inference.

“Hyperscale is seeing great traction and great demand,” explained Huang. “Supercomputing centers all over the world are building out, and we are really in a great position there to fuse, for the very first time, simulation-based approaches with data-driven approaches that are called artificial intelligence. So across the board, our datacenter business is gaining momentum. We see great strength now, and it is strengthening and we are really set up for years of growth in the datacenter. This is the largest segment of computing, and is going to continue to grow for some time to come.”

One of the keys to that growth is the partnership that Nvidia has with VMware, which is by far the preferred virtualization platform in the enterprise and that has worked with Nvidia to port its ESXi hypervisor to run on the BlueField DPUs, much as AWS has moved its own KVM hypervisor to run on its homegrown Nitro DPUs. The idea is to virtualize networking and storage access and get these as well as encryption and other security workloads off the CPU cores in a server and into the DPU cores and, in Nvidia’s case, their GPU accelerators. Huang reiterated Nvidia’s claim that a BlueField-2 DPU can replace the work done by around 300 cores running inside of servers that host these various workloads, which is a huge amount of compute. Huang added that somewhere on the order of 50 percent of the cores in the modern datacenter were doing such adjunct work, and that pulling these workloads off CPU cores and onto DPUs represented a huge opportunity and said further that he expects every server will eventually have a DPU.

We don’t disagree.

One other interesting thing that Nvidia did in the April quarter. Cryptocurrency miners have been buying up GeForce RTX cards in droves, which has been curtailing availability of these devices for gamers while at the same time driving up the prices. And so Nvidia has created a separate line of cryptocurrency mining products, or CMPs, that don’t have a lot of graphics functions and their own pricing and has at the same time cut the hash processing capabilities of the RTX 3060, 3070, and 3090 cards based on the Ampere architecture in half to make them unappealing to cryptocurrency miners. And, so people are not guessing how much money Nvidia is making on sales of GPUs to cryptocurrency miners, it is now reporting these revenues separately in its OEM and IP segment. In the first quarter, Nvidia had about $155 million in such sales, and expects another $400 million in sales in the second quarter. This is a good business, for sure, but it is as ephemeral as bitcoins are not supposed to be. And now it is not being reported in the Datacenter division, so when it collapses (yet again) it won’t make that core HPC and AI business look weak.

ARM Holdings should always remain an Independent IP Licensing entity and never be allowed to be under the control of any present or past ARM Holdings licensee! Nvidia is free to license whatever it needs from ARM Holdings currently so what excuse does Nvidia have for needing to control Arm Holdings and that IP and the ARM ISA licensing apparatus!

There are a few basic tenants to estimating Nvidia component sales. Mr. Huang advised in 2021 Nvidia sold 100 M units; 16.675 B / 100 M = $166.75 net per unit. This is within the range of Intel average Core competitive to which all PC component design producers strive in terms of cost : price / margin.

Analytically I believe Nvidia component growth rate is doubling doing for the first time in 30 years what Cyrix and AMD should have done. In Cyrix’s case JV exclusively with TI and then missed a second time with IBM. And in the AMD example JV with Global Foundry 2015/16. That opportunity was certainly on the table? There would have been no supply questions as there are now none discernable on Nvidia Samsung teaming. Samsung for decades needed high margin volume sales as a price margin support against high volume commodity fabrication and now has it. As long as everyone gets along Nvidia supply is unquestionably unrestrained and unlimited.

Back to those basic GPU tenants; bottom bin like Polaris appear to sell for around $43 to $47 a pop think Pentium OEM pricing.

AMD average let’s call it competitive price sell for around $80 and Nvidia gets a premium lets call this top of i3 bottom of i5.

Last two quarters of Nvidia miner sales were not necessarily bottom bin on those SKUs available, many secured from secondary market brokers clearing channel inventory which is as lean as its been in three years. For into future CMP _HX guestimate; $150,000,000 / $80 = 1,875,000 components and on Nvidia q2 guidance $400,000,000 / $80 assuming this is essentially slack from the dice bank = 5,000,000 components. On this method of estimation Nvidia is assuring against commercial mining taking a third of Nvidia quarterly consumer production. Pascal 1060 in 2017 went to mining I’ve estimated 10 M cards as a percent of GTX 10×0 full run. Commercially, the segment I place mining, might have snapped up another 10 M cards which would be equivalent to around one quarter of Nvidia consumer production that currently seems in the 11 M and definitively heading toward 15 M units per quarter range.

Here’s Nvidia component category break down on channel inventory holding data;

Tesla between Accelerators and tip top of science cards = 7.27%. Note that commercial data is somewhat hidden on channel inventory levels that are cards offered by open market broker dealers.

Professional Visualization = 12.18%

Top Shelf Consumer = 71.67%

Mass Market Consumer = 6.75%

Consumer Mobile = 2.13%

So how many and what kind of Nvidia components sold for $5.3 Billion in q1? If we rely on Mr. Huang 100 M units annual the first thing one might notice is average net jumped up from $166.75 to $212 per unit but it’s difficult factoring in developer appliances, compute systems and embedded subsystems.

How about just looking at $2.760 B gaming, $372 M professional visualization and $2.048 B data center revenue in q1 2021 (Nvidia q1 ’22).

Whether AMD aim or Nvidia ability to secure, $180 appears the average net sought for consumer dGPU; $2.760 / $180 = 15,333,333 components. 60 M units annual is approximately the historical top of Nvidia consumer line production.

Professional visualization at $372 M difficult to say on the question of Nvidia professional card sales combined with appliance development and compute system inclusion. Or is it data center that includes appliance and compute systems? Let’s take a guess. Intel likes double Core line OEM average or what would be the equivalent of 1K. lets use Comet Lake 1K across full line $339 and multiple times 3 or 4 for a competitive card product = $1019 to $1395 would be in the consumer MSRP range for AMD Instinct and professional and Nvidia has to be competitive; range 243,844 to 301,275 cards presents a low volume anomaly in relation percent of channel inventory holdings.

Now the hard one, data center and this will be for large memory accelerator. Instinct M125 goes in the channel for $1000 and Nvidia cards currently appear price inflated Tesla A100 developer reference cards in the channel range $11 K to $15 K. Let’s consider RTX A6000 selling for $5500 in the channel / 2 wholesale = $2750. Now add that data center is a commercial sale and data centers have price making power. Let’s double prior $339 dGPU component competitive price to $678 that is Intel full product line economic profit point continuing the thesis all design producers attempt to emulate Intel margin. $678 x 3 for the subsystem wrapper = $2034.

Nvidia q1 data center at 2.048 B / $2034 = 1,006,883 cards and or subsystems.

Finally lets break Nvidia sales aim out by product category on channel data across 120 M units through the year;

Commercial Accelerators = 6,615,246 dGPU

Top of Science = 2,106,215 dGPU

Professional Visualization is the ‘high’ anomaly on this pondering = 14,615,070 units.

Top Shelf Consumer = 86,006,392 cards also thought extending into mobile on 30×0 Max-q.

Mass Market Consumer = 8,098,668 cards.

Mobile as in MX and Max-q and yes it’s back looking and seems low but channel data is good for this = 2,558,410 units.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing