D-Wave today announced another milestone in its quest to keep adding qubits, jumping from the previous generation 2000 qubit device to one with 5000. This is a notable achievement that doubtlessly will be written to death elsewhere from a quantum progress point of view but should probably be discussed from a quantum market transitions one.

There are two big issues at hand for D-Wave, the only maker of standalone quantum annealing hardware. The first takes us back to 2014 or so when the vision was that eventually, with enough of the pieces in place for facilities, programmers, and workloads, many of the largest computing sites in the world would have a big shiny quantum computers sitting next to traditional datacenter gear, acting as a sort of super accelerator for key parts of important applications. Simply put, those were the days when it seemed like D-Wave was purely in the hardware business. It still is, but the model has shifted. More on that in a moment.

The second consider is how feasible it is for D-Wave to continue having massive jumps in qubit counts based on what is technologically possible. We’ll get to that in a moment as well.

But the third thing, the trickiest one to address without first unpacking the above, is where annealing systems will fit in future HPC, enterprise, and hyperscale—not just if at all, but in what form. It is increasingly likely that the quantum offload of the future will look much like magical machine hooked in with traditional supercomputers, gleaming on some datacenter floor and more like, well, a laptop screen where programmers engage with the quantum cloud.

And that brings us to the fourth thing. If the quantum business and all of its expensive hardware is only serving a hardware market where it is own largest customer (so the services can be rented) how can this be a lasting business at all? That means quantum companies are competing on the usability of their software and interfaces in addition to hardware and that is going to be tough and limiting, especially for the non-IBMs and Googles of the world, and perhaps especially for the one lone startup doing quantum differently altogether.

We appreciate Mark Johnson, VP Processor Design and Development at D-Wave for being a good sport. We wanted to talk architecture (which we did) but these days it’s getting more difficult to tease the technology out from the business, TAM, and other matters. When we talked to him about the 5000 qubit announcement it was also difficult not ask where the ceiling might be with big chip leaps and if D-Wave didn’t ensure there would be enough room to ensure an equivalent jump on its Intel-Like cadence of processor innovations. And he gave some good answers and insight into where growth might be and if a pivot away from a hardware (on-prem) market for quantum is the path forward.

D-Wave certainly does have room to grow in terms of processor capability and manufacturability. The lithography for their chips is using the quarter-micron 250 nm, after all. Yes, the same one from the late 1990s—the one that’s cheap now, relatively speaking. “We have plenty of room to move in terms of feature size,” he tells us. “We made a big jump in the stack and we have the next processor in mind and think we can keep getting more out of this new stack. It’s going to be a continuing journey.” He added that the fabrication technology they’re using will continue on in much the same way we’ve seen steady process in semiconductors since the early 1970s.

D-Wave has added to its design teams, Johnson says, but in terms of manufacturing and fabrication, those are the “easy” parts. “It’s really about the work required to develop the technology, once it’s up the rest follows along. It’s a more complicated process for this newest device, getting all the functions on the chip, more layers, more and different materials than we had before, and in general that all adds more complexity. He didn’t believe there had been a hockey stick uptick in what it cost to make the chip from a production standpoint—it’s all in R&D.

But it’s still an expensive business to be in. The question as posed above is whether or not the returns will be there without the big systems to sell as standalone hardware devices. When asked about the future of quantum as a hardware business, Johnson says, “We are a hardware provider in the sense that we’re building quantum computers, we have been and will continue that. But the best way to deliver value to end users with quantum is with a cloud and not delivering the actual computer.”

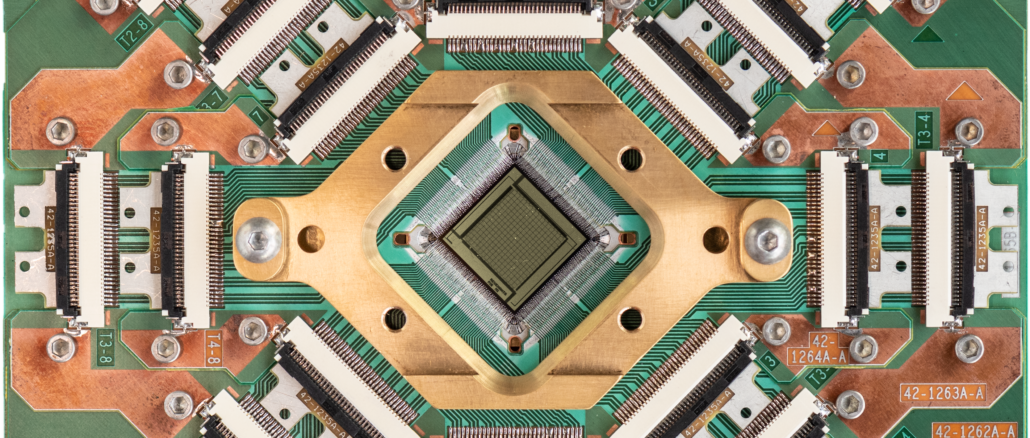

Just for a sense of the investment required to make the leap from 2000 to 5000 qubits, he described the development of enhanced superconducting integrated circuit technology and all of the control logic both in hardware and software that’s required. For instance, the 2000 qubit product had about 128,000 Josephson junctions (think of those very loosely like a transistor in the semi space). For the new “Advantage” product there are more than a million. He says it took several years to get just the fabrication end of that down to a science.

In terms of other elements, consider what goes into one of the 8 square millimeter chips. Among other expensive, exotic (and some common) pieces, including 110 meters of quarter-micron thick superconducting wire. 91,000 superconducting flux stacks (a 5X addition over previous generation). “The point of all this extra control circuitry and new, improved multiplexing schemes to drive this…we’ve been working on all this since before we released the last product in 2017—well before that.”

What we’re driving at here is that the leaps between generations of technologies are never easy or cheap, this much is clear from watching the tick tocks from other industries. But D-Wave is blazing its own trails. It can’t use the same approaches the gate model folks use, it really has to (and has) built from the ground up. All of that (sort of) made sense if the ultimate goal was selling into the world’s largest datacenter as a specialized kind of accelerator but if that’s no longer the case, how do these business keep on making a business.

Here’s an old conversation we had with then CEO of D-Wave, Vern Brownell way back in 2018, back when the world might have been getting pumped to install quantum systems at national labs and large enterprises. Much seems to have changed with the cloud focus. While it might not be good news from a hardware business standpoint for quantum, it could engage far more of a user base to usher a golden era of many new quantum applications, even hybrid applications that offload bits and pieces for certain optimization functions. But still, it’s a tough business. Especially with IBM and Google leading the R&D charges. What’s different now, however, is that there’s a whole lot more government money being doled out to support quantum efforts. This might be the saving grace for this entire industry but there likely won’t be room in the market for a while for more than a couple vendors to dominate. Where that leaves D-Wave and Rigetti and some of the startups who took big risks and saw big returns on the horizon is still anyone’s guess.

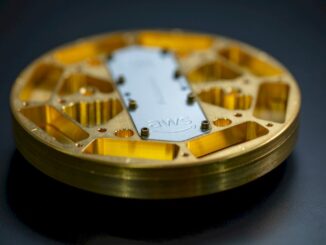

For now, progress marches on, whether or not the market needs have been defined (or even rerouted entirely). D-Wave has been an innovative company from the beginning and even managed to secure some high-profile end users early on to validate early use cases (Los Alamos, Volkswagen, etc). But renting a few minutes of quantum cloud time doesn’t have the same appeal as investing in a machine with its chilly, gilded, space-age presence and we have to wonder, if it is no longer about the hardware business was it ever about anything other than the hardware itself?

Be the first to comment