The hyperscalers and cloud builders of the world put a third of their installed base into the trash compactor every year because it is much less costly for them to keep upgrading machinery than it is to operate older stuff that eats space and burns power and cooling less efficiently. And, they also needed to get a big chunk of their server fleets updated so they would be able to do mitigation against the Spectre/Meltdown speculative execution vulnerabilities that they have known about for nearly two years now – a good seven months before the rest of the world did.

Scale matters, we suppose.

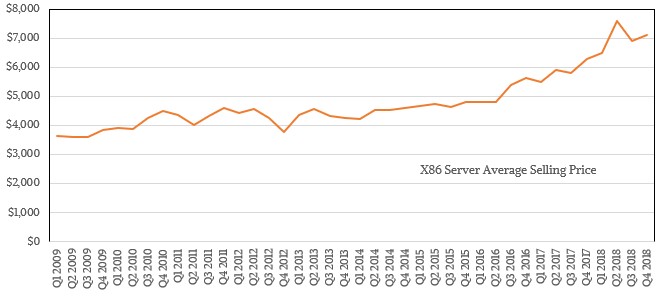

In any event, with revenues growing like crazy at these infrastructure giants – somewhere between 20 percent and 40 percent, depending on the company and the quarter – there is a built-in rate of spending on servers for these big companies. And when you add in the higher prices that Intel has been able to charge for capacity on its “Skylake” Xeon SP processors, plus the higher cost of memory and flash, plus the generally richer configurations for machines (including GPUs and sometimes FPGAs), it is no wonder that the server market turned in a killer year in 2018, even if revenues across all makers did slow a bit as the hyperscalers and cloud builders took a breather in the final quarter of the year.

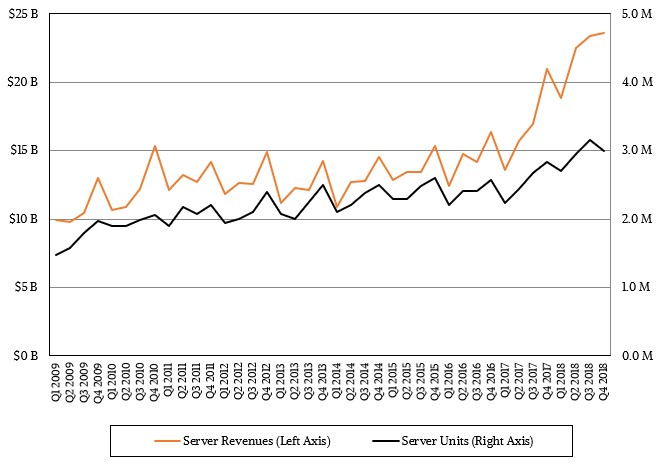

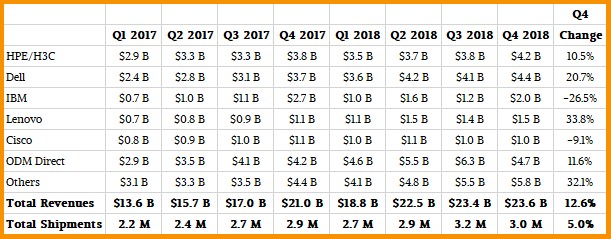

Server spending is a proxy of sorts for the overall health of the IT sector, which is why we care about it in addition to just being curious about what is happening with the most important part of the datacenter. Server shipments were up 5 percent to 2.99 million machines in Q4 2018, according to the latest statistics from IDC, which is a bit less than many were anticipating. But that shipment rate, curtailed by the Super 8 spending a bit less than anticipated, was still sufficient for all of the reasons we outlined above to drive revenues up 12.6 percent to $23.62 billion. This is, in case you don’t have a long memory, an incredible amount of money spent on servers – nearly double the pace from only three years ago.

For the full year, server revenues were up 31.4 percent to $88.33 billion – a record year and perhaps setting the stage for a $100 billion server year, the world’s first, in 2019.

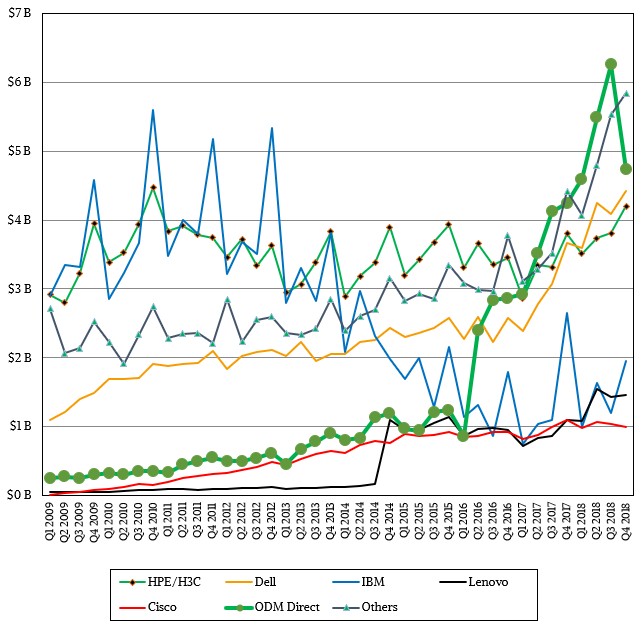

Among the major ODM suppliers that IDC tracks separately and that are the big suppliers to the hyperscalers and cloud builders – this includes Quanta Computer, Inventec, WiWynn, Foxconn, and a few others – spending was subdued in Q4, rising only 11.6 percent to $4.74 billion. It is important to not equate this ODM line item in the server stats linearly with the hyperscale and cloud markets, since many OEM vendors have custom server units that also sell to the Super 8; for instance, Inspur does big business with Alibaba and Tencent in China and Dell does big business with Microsoft, as Hewlett Packard Enterprise still does from time to time but less so after it has backed out of this part of the market where margins are laser beam thin. But it is a proxy of sorts for the appetite that the Super 8, who collectively probably consume somewhere around 40 percent of the world’s server units per year, when it comes to server spending. And it was definitely muted, and probably as these companies await the future “Cascade Lake” Xeon SP processors from Intel and the “Rome” Epyc processors from AMD, both of which have hardware mitigations to defend against the Spectre/Meltdown vulnerabilities. While server spending across the ODMs slowed down in Q4, for the full 2018 year, it rose by 42.3 percent to $21.1 billion. So no one would call it a bad year.

Given the ups and downs of the hyperscale, cloud, and HPC sectors of the server market and the capriciousness – some might say skittishness – of enterprises when it comes to buying hardware in recent years, it is perhaps best to look at the market on an annual basis as well as quarterly, as is shown for sales by vendor in the chart above and in the table below:

Money is what matters, so we will focus here. Dell was the market leader in 2018, with $16.36 billion in revenues for servers, according to IDC, an increase of 37.5 percent compared to 2017. Dell’s server business, as we showed in our analysis two weeks ago, is growing fast and getting more profitable, which was one of the themes of founder Michael Dell taking the company private several years ago. Hewlett Packard Enterprise is not growing as fast as the market, mainly because it is backing away from chasing the low-margin or no-margin hyperscale, cloud builder, and service provider business it once coveted. Still, the company, including sales of its H3C partnership in China, brought in $15.26 billion in server revenues in 2018, up 14.5 percent, making the company the number two seller in the world.

Inspur, which sells like an OEM as well as an OEM and which also has a partnership with IBM to sell its own variants of servers based on Big Blue’s Power9 processors, is coming up fast and giving both IBM and Lenovo a run for the money. As best as we can figure, Inspur more than doubled its server revenues in 2018, to $5.35 billion. Lenovo, which ate IBM’s System x X86 server business four years ago, has been able to leverage that acquisition to get the number four ranking by revenues in 2018, with $5.53 billion in sales, up 57.6 percent. IBM’s System z mainframe had a huge fourth quarter last year, and a pretty good first half of 2019, and the company’s own Power9 servers started ramping through 2018, so it was able to hold onto the number three position with $5.77 billion in sales, up only 4.3 percent. As we have pointed out many times, IBM’s overall systems business is more than four times as large as this if you count operating systems, middleware, tech support, and financing, and it has operating income of between 55 percent and 65 percent, so there are reasons why Big Blue chooses to stay in a low volume, extremely high margin server business and walked away from the skinny margins and high volumes that others suffer through.

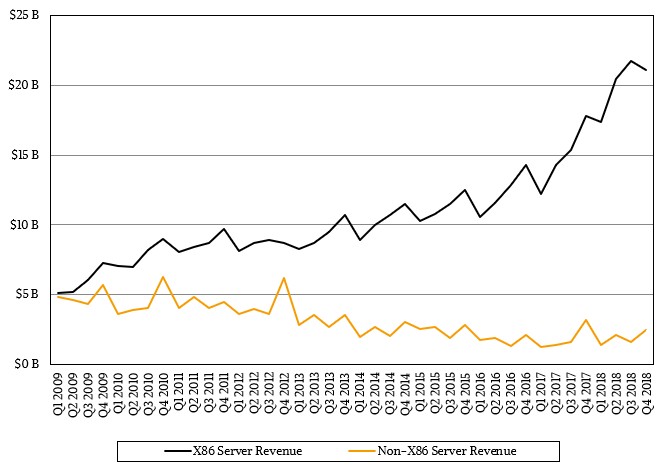

The X86 server, which still mostly means machines based on Intel’s Xeon processors, still dominates the datacenter, although Intel has seen some sales pulled away by the success of the “Naples” Epyc processors from AMD (particularly among cloud builders) and from Arm server chips made by Marvell. The market has been growing faster enough that even as AMD and Arm make headway it hasn’t really hurt Intel’s Data Center Group, which also turned in record quarters throughout 2018. This did give Intel a bit of a haircut on revenues and profits in Q4, just the same. Just a little off the top. For the full year, X86 machinery drove $80.69 billion in sales, up 35.2 percent, and a total of 11.5 million machines, up 13.7 percent year on year.

By contrast, non-X86 iron, which includes all Arm servers, all Power servers, all System z mainframes, and all of the other few remaining proprietary architectures and RISC or Itanium big iron that is still shipped here and there, which was about 310,000 machines last year, accounted for $7.64 billion in sales, up 3 percent believe it or not. There is still a place for big iron in the datacenters of the world, and not all of it is based on the X86 architecture. There is still a chance that Arm will catch on in the datacenter and that Power will carve out its slice, but AMD is sure making that progressively harder with the Naples and Rome Epyc chips.

Accelerated computing models, which offload all or part of applications to GPUs and FPGAs are diminishing X86 server sales, too, but the resulting hybrid machines generally have X86 processors in them as host processors, so neither Intel nor AMD will have to admit defeat. And in fact, they know it is not defeat at all, but rather a necessity in a world where you can only cram so many transistors on a die at a certain cost as manufacturing processes – and particularly the factories that employ them – get tougher and more expensive. General purpose computing is still going to be around for a while, but compute is probably going to be a hodge podge of components as a matter of course for all kinds of workloads in the not too distant future. This is what happens when Moore’s Law at a chip level slows down with age, as it most certainly has done.

All we know is that 2019 stands to be a whole lot more competitive than 2018 was, and 2020 is lining up to be a real doozy. And that is good for everyone in the long run. Particularly if the appetite for compute is growing is much larger than it has historically been. Imagine if you adjusted the revenue and shipment plot lines above for the past nine years to show the aggregate amount of compute delivered each quarter. If you do some rough math on the back of the envelope – well, in a spreadsheet – then the world consumed somewhere between 15X and 20X more raw compute in servers in 2018 than it did in 2009. And the price/performance of that capacity has improved by around a factor of 8X, which is how the world can sustain that appetite for compute.

Be the first to comment