In a properly working capitalist economy, innovative companies make big bets, help create new markets, vanquish competition or at least hold it at bay, and profit from all of the hard work, cleverness, luck, and deal making that comes with supplying a good or service to demanding customers.

There is no question that Nvidia has become a textbook example of this as it helped create and is now benefitting from the wave of accelerated computing that is crashing into the datacenters of the world. The company is on a roll, and is on the very laser-sharp cutting edge of its technology and, as best as we can figure, has the might and the means to stay there for the foreseeable future.

Nvidia has every prospect of being able to get a very large portion of the $30 billion in addressable markets that it is chasing with its Tesla accelerators in its datacenter product line – mainly traditional HPC simulation and modeling and machine learning training and inferencing – and is well on its way to fomenting new virtual workstation markets with its GRID line and instantaneous video transcoding and GPU accelerated database with its Tesla line, all of which are outside of that $30 billion total addressable market and which represent other very large opportunities.

It is no wonder that a bunch of executives from Cisco Systems have come to Nvidia – John Chambers, the former CEO at the company, is legendary in taking a router company that was at the beginning of the commercial Internet revolution to new heights by finding adjacencies and expanding into them. Cisco did it through a combination of internal investment and acquisition, while Nvidia is doing it mostly through finding new markets and creating them. Cisco essentially outsourced the job – sometimes quite literally with its UCS servers and Nexus switches – and it is interesting to contemplate if Nvidia might do some acquisitions of its own to help build out its datacenter business. To have a true platform, Nvidia needs a processor and networking, but it only has $5.9 billion in cash as of the end of its second quarter of fiscal 2018 ended on July 1. We have suggested that if IBM had any sense, it would have bought Nvidia, Mellanox Technologies, and Xilinx already. But maybe these four vendors should create a brand new company, each with proportional investment, that has all of their datacenter elements in it and call it International Business Machines, leaving all the rest of the IBM Company to be called something else.

It’s a funny thought, but the world needs a strong alternative to Intel, and even though AMD is back in the game, it is not yet making money even if it is making waves.

Before we get into the detailed numbers for the second quarter, we wanted to outline the addressable markets in the datacenter that Nvidia has identified and quantified. It all started with gaming with Nvidia, and this is the revenue stream that allowed the company to branch out into the adjacencies in the datacenter, much as Microsoft jumped from the Windows desktop to the Windows Server and Cisco jumped from routers to switches and collaboration software and video conferencing and converged server-network hybrids. The gaming business was just north of an $80 billion market, with 2 billion gamers worldwide and 400 million PC gamers who buy rocketsled PCs with fast CPUs and GPUs; this market is expected to be around $106 billion by 2020, growing at 6 percent annually. This is not huge growth, but it is a very large business and it has the virtue of not sinking. Nvidia’s GeForce GPU graphics card business is far outgrowing the business, with revenues expected to grow 25 percent per year between 2016 and 2020, and average selling prices rising 12 percent and units rising 11 percent.

So far, the installed base on gamer PCs is about 14 percent on the “Pascal” generation of GPUs that came out in 2016, and another 42 percent are on earlier “Maxwell” GPUs, with the remaining 44 percent on earlier “legacy” GPUs, as Nvidia calls them. This is a huge installed base that will gradually upgrade to new iron, and with the Pascal GPUs being very good compared to the AMD alternatives, there are good reasons why Nvidia is not rushing GeForce cards based on the current “Volta” GPUs to market. For one thing, as Nvidia co-founder and CEO Jensen Huang said during his call with Wall Street analysts that it costs about $1,000 to make the hardware in a Volta GPU card, give or take, and this is very expensive compared to prior GPU cards – all due to the many innovations that are encapsulated in the Volta GPU, from HBM2 memory from Samsung to 12 nanometer FinFET processes from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp to the sheer beastliness of the Volta GPU. This Pascal upgrade cycle on GPUs for gamers and workstations, plus the regular if somewhat muted hum of the normal PC business, is an excellent foundation from which Nvidia can invest in new markets, as it has in the past.

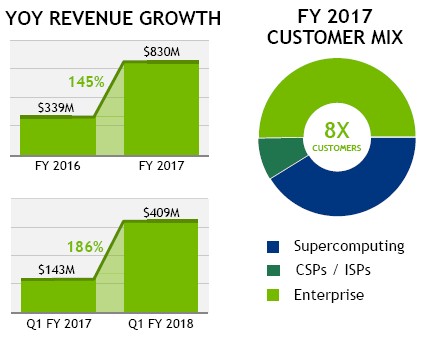

Here is the customer mix that Nvidia’s datacenter business, which sells the Tesla and GRID accelerators as well as the DGX-1 server line and now workstations, for fiscal 2017:

It is important to not confuse customer share with revenue share or aggregate computing share. We think, based on statements that Nvidia has made in the past, that the hyperscalers are spending a lot more dough on Nvidia iron than the supercomputing centers of the world, so that pie chart above shifts a bit when you start talking about money. The important thing is that over 450 applications have been tweaked to run on the CUDA parallel computing environment and can be accelerated by GPUs, and there are myriad more homegrown applications that have been ported to CUDA as well. The Tesla-CUDA combination is a real platform in its own right, and it is at the forefront of high performance computing in its many guises.

An aside: Nvidia is now shipping DGX systems that employ the Volta GPUs, which we profiled here, and has shipped DGX iron using either Pascal or Volta GPUs to over 300 customers and has another 1,000 in the pipeline.

Here is how Nvidia cases out the three core markets for its Tesla compute efforts:

Nvidia thinks that the amount of compute aimed at traditional HPC workloads will grow by more than a factor of 13X between 2013 and 2020, reaching 8 exaflops in aggregate by the end of that period and representing a $4 billion opportunity. One could argue that it is very tough to create exascale machines without some kind of massively parallel, energy efficient processor, and the reason is that CPUs that are good at serial work burn too much energy per unit of work, so you have to use them sparingly. It takes a lot less money to build a fat server node with lots of flops, and provided the applications can be parallelized in CUDA, you can see more than an order of magnitude in node count contraction and an order of magnitude lower hardware spending by moving to hybrid CPU-GPU cluster over a straight CPU cluster.

Intel knows this, and that is why the Knights family of Xeon Phi processors exist.

As you can see, the TAM for deep learning – for both training and inference – is expected to be a lot larger than the TAM for traditional HPC by 2020, according to Nvidia. And the amount of computing deployed for these areas is also expected to growing a lot faster than for HPC. By Nvidia’s reckoning, the amount of aggregate computing sold in 2020 dedicated to deep learning training will hit 55 exaflops in 2020 and will drive $11 billion in revenues, up from 1.4 exaflops in 2013 and an untold (but probably well under $100 million) in revenue that year. Deep learning inference, which is utterly dominated by Intel Xeon processors these days, will be an even larger market by 2020, with around 450 exaiops (that’s 450 quintillion integer operations per second of capacity, gauged using 8-bit INT8 instructions that are commonly used these days for inference) and racking up $15 billion in sales. Nvidia is now demonstrating an order of magnitude in savings over CPU-only solutions using its Pascal GPUs, but it remains to be seen if it can knock the CPU out of deep learning inference.

We think that virtual workstation clusters and database acceleration represents billions of dollars more TAM for the Nvidia datacenter business, and we also think that IoT will drive some more, at both the edge of the network and in the physical datacenter itself.

“The number of applications where GPUs are valuable, from training to high-performance computing to virtual PCs to new applications like inferencing and transcoding and AI, are starting to emerge,” Huang explained on the call. “Our belief is that, number one, a GPU has to be versatile to handle the vast array of big data and data-intensive applications that are happening in the cloud because the cloud is a computer. It is not an appliance. It is not a toaster. It is not a lightbulb. It is not a microphone. The cloud has a large number of applications that are data intensive. And second, we have to be world-class at deep learning, and our GPUs have evolved into something that can be absolutely world-class like the TPU, but it has to do all of the things that a datacenter needs to do. After four generations of evolution of our GPUs, the Nvidia GPU is basically a TPU that does a lot more. We could perform deep learning applications, whether it’s in training or in inferencing now, starting with the Pascal P4 and the Volta generation. We can inference better than any known ASIC on the market that I have ever seen. And so the new generation of our GPUs is essentially a TPU that does a lot more. And we can do all the things that I just mentioned and the vast number of applications that are emerging in the cloud.”

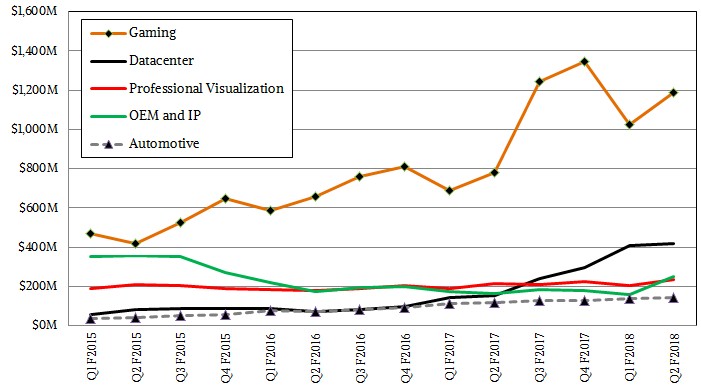

Having said all of that, Nvidia’s second quarter was hampered a little bit by the transition to the Volta GPUs and by Intel’s delayed rollout of its “Skylake” Xeon EP processors and their “Purley” server platform. We and Wall Street alike had been thinking the datacenter business would do better than it did – we expected around $450 million based on past trends and the explosive uptake of Pascal accelerators – but the datacenter business only brought in $416 million in the second fiscal quarter.

That said, the Datacenter division saw 175 percent growth year on year and managed to grow sequentially by 1.7 percent sequentially, which is no mean feat with two product transitions under way. (Three if you count the Power9 processor from IBM that Nvidia is tied to in some important ways, namely NVLink.) Nvidia does not break out Tesla and GRID sales separately, but we reckon GRID revenues were flat sequentially at around $83 million, and that the rest was Tesla units, up a smidgen sequentially at $333 million. If these estimates are close to reality, then the Tesla line alone now accounts for 15 percent if Nvidia’s revenues, and certainly a much higher proportion of its profits.

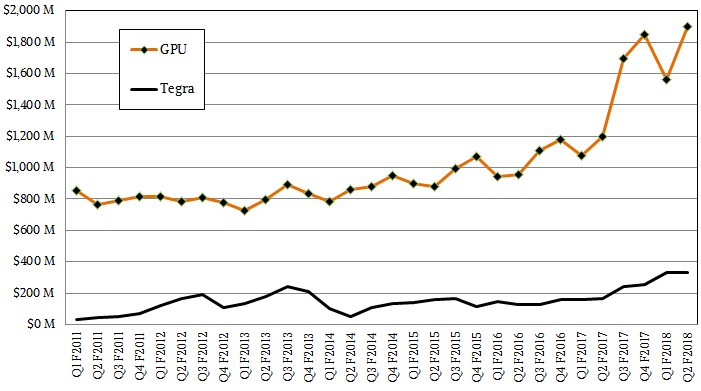

For the quarter, Nvidia sold just under $1.9 billion in GPU products, and $333 million in Tegra CPU-GPU hybrid products that are used in handheld gaming devices, drones, and autonomous driving platforms and other things we either don’t care about or hate here at The Next Platform. The Professional Visualization division of Nvidia, which we do care about and which sells Quadro workstation GPUs, posted $235 million in sales, up 10 percent year on year, and the core gaming business, driven by the GeForce GPU cards for PCs that make Nvidia’s ever-expanding business possible, had $1.19 billion in sales, up 52 percent. The OEM and IP business was a mixed bag, with the quarterly $66 million in royalty payments from Intel gone now, but with specialized GPU sales aimed at blockchain and cryptocurrency applications coming in at around $150 million (of the $251 million of OEM and IP revenue in the period), the overall Nvidia business made up for the what has to be called a minor slowdown in the Datacenter division (despite its growth) and the absence of Intel cash.

A lot of people think that blockchain and cryptocurrency is a fad, but it isn’t, and frankly it will be part of people’s platform and we will be looking into it in some detail without getting all gee-whiz about it.

“Cryptocurrency and blockchain is here to stay,” Huang said on the call. “The market need for it is going to grow, and over time it will become quite large. It is very clear that new currencies will come to market, and it is very clear that the GPU is just fantastic at cryptography. And as these new algorithms are being developed, the GPU is really quite ideal for it. And so this is a market that is not likely to go away anytime soon, and the only thing that we can probably expect is that there will be more currencies to come. It will come in a whole lot of different nations. It will emerge from time to time, and the GPU is really quite great for it. Our strategy is to stay very, very close to the market. We understand its dynamics really well. And we offer the coin miners a special coin-mining SKU. We know this market’s every single move and we know its dynamics.”

It is not clear if these mining SKUs are based on Pascal or Volta GPUs. Huang said that the Volta GPUs were fully ramped, but what that really means is that the Volta-based Tesla V100 accelerators as used for very high end HPC and AI gear are shipping, but you can’t really say that the Voltas are fully ramped until there are desktop, workstation, and Tegra units in the market. That could take some time, and it is significant that at the GPU Technical Conference back in May Nvidia did not provide even a hint of a product roadmap. The transition to Volta could take a long time, and a lot depends on what the competition – particularly that from AMD and Intel – does.

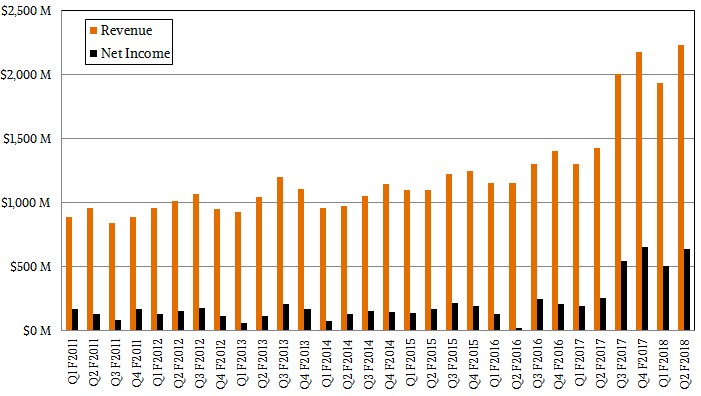

We know one thing for sure. Nvidia is on track to be a $10 billion company this fiscal year, with maybe 25 percent of that coming in as net income, and that is quite a feat. Nvidia’s Datacenter division is one of the reasons it can grow that much and be a respectably profitable company. Raking in $2.23 billion in sales and bringing $638 million of that to the bottom line is the second in four steps to get there.

Be the first to comment