Might doesn’t make right, but it sure does help. The hyperscalers, cloud builders, and co-location datacenters of the world that operate at massive scale have an interconnectivity problem, and it has nothing to do with the feeds and speeds of a switch. What is choking them is the Ethernet cable, and they are working together to do something about it.

It may be hard to believe, but the cabling in the datacenter that allows for the communication between servers, storage, and the outside world in a modern distributed application cost more and are more of a limiting factor in a warehouse-scale datacenter (as Google calls glass houses with something on the order of 100,000 servers) than any other element. The reason is because applications now spend more time and bandwidth communicating across server and storage nodes inside a datacenter than they do talking with the outside.

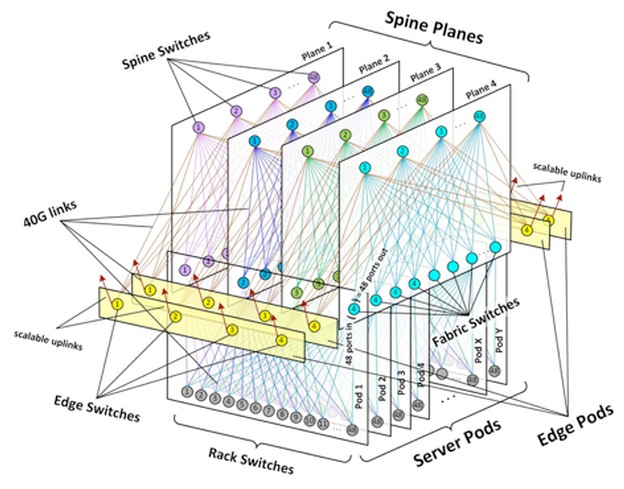

When you have that many machines in one place, you have some very long links indeed to be able to build a network fabric that can lash all of those machines together in an efficient fashion. (The Clos network seems to be the choice that Facebook, Microsoft, and Google have all come up with.) As Katharine Schmidtke, sourcing manager for optical technology strategy at Facebook explained at the recent Open Compute Summit in San Jose, one of Facebook’s datacenters has tens of thousands of kilometers of fiber optic cables linking nodes together in a fabric that allows reasonably consistent and fast access from any two nodes in the network.

Google’s homegrown networking stack and fabric, as we have detailed before, doesn’t look that much different, although Google has been making its switches and network operating system longer than any of the other hyperscalers. (Facebook has been agitating for open switches and cheaper optics for the past several years.) The hyperscalers moved to 40 Gb/sec Ethernet years ago, and as they make the transition to 100 Gb/sec and look to the future of 200 Gb/sec, 400 Gb/sec, and 1 Tb/sec networks that are on the Ethernet roadmap, they want to lay down fiber plant, as the physical network is called, that can be used for multiple generations. There is not precise agreement among the hyperscalers, cloud builders, and service providers about a specific technology, but they all seem to be in agreement, based on statements made at the Open Compute Summit, that the OM3 and OM4 multi-mode fiber that has been deployed since 10 Gb/sec Ethernet networks were commercialized and that has been carried forward during the 40 Gb/sec generation is not the answer.

Without getting too much into the physics of lasers and optical transport materials, cranking up the bandwidth higher on multi-mode fiber doesn’t work as well as it does for single mode fiber. But, the single mode fiber that was developed by the telecommunications industry to do long haul network segments of up to 10 kilometers has been too expensive to be deployed inside the datacenter in any kind of volume. This is actually one of the limiting factors holding back the typical order of magnitude jump in network speeds that the entire IT industry had been trained to expect from Ethernet. The jump from 10 Gb/sec to 40 Gb/sec was not just a limitation of switch ASICs, but also fiber optics.

Facebook has been working for the past year and a half to come up with a solution to its fiber interconnect problems, and Schmidtke says that it has chosen a single mode fiber optic cabling solution that it has worked with the industry to tweak so it can work over datacenter distances and be a lot less expensive than the longer haul single mode fiber that has currently been available for 100 Gb/sec links.

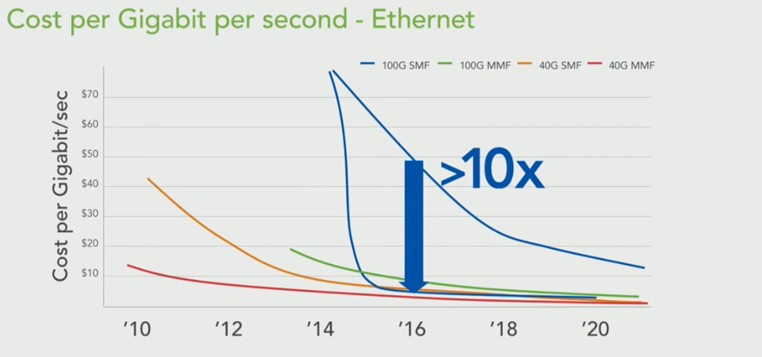

In the chart above, the red line shows 40 Gb/sec multimode fiber and how it is considerably less expensive for a given unit of length (Schmidtke did not give that length) compared to single mode fiber running protocols at the same speed. In 2010, it was basically four times as expensive, by 2012 it dropped to two times, and by last year it was about a 50 percent premium. Multimode fiber for 100 Gb/sec networks is about as expensive as 40 Gb/sec cabling was back in 2012 or so, but Facebook is not just thinking about one generation. It wants to put in a duplex pair of single mode fiber today that will get it through 200 Gb/sec, 400 Gb/sec, and 1 Tb/sec network bandwidth jumps, but with the current price of this cabling, which is rated for 10 kilometer distances, it was absolutely not affordable for datacenter use.

So Facebook has worked with the industry to shorten the cable links to 500 meters or less in length, put on cheaper cable coatings that are fine in the datacenter even if they do shorten the lifespan a bit (theoretically), and at the same time forced cable makers to lower the temperature range of the CWDM4 transceiver so they didn’t overheat the datacenter. With these changes, the single mode fiber is suitable for connecting rows of infrastructure or different rooms inside datacenters together. These changes drop the blue line in the chart above by a factor of 10X so single mode fiber supporting 100 Gb/sec protocols can cost about half that of multimode fiber today, and cost the same or a little less than single mode fiber supporting 40 Gb/sec protocols.

Now, Facebook wants to pump up the volume of manufacturing on this cabling to drive the price down lower, and it looks like Microsoft could be on board. Google was not specific about its cabling at the OCP event, but it could pipe up at some point. Datacenter operator Equinix spoke a bit about how it wanted an open standard for cabling without actually committing to any particular technology.

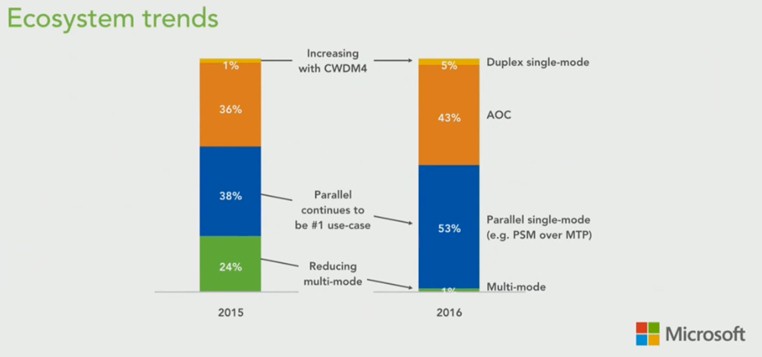

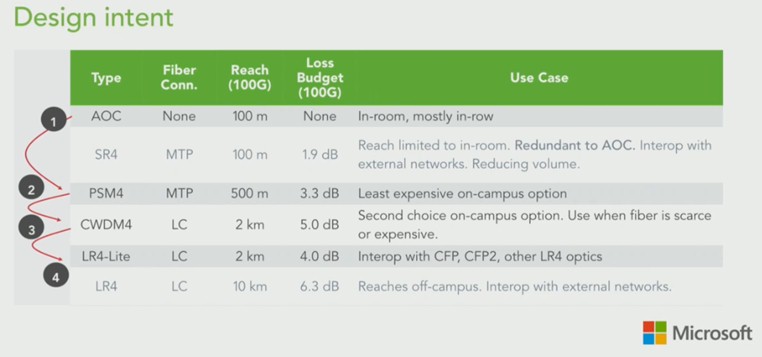

Jamie Gaudette, senior manager of WAN optical architecture and technology at Microsoft, gave some insight into the cabling strategies inside Microsoft’s Azure cloud. Here is how the current cabling breaks down in the datacenters:

The AOC cables are low-cost cables that have permanently fixed ports at the ends that are good for linking gear inside of racks and across rows – what we think of as the normal stuff. And this cabling is going to grow in the next year inside of Microsoft’s datacenters, not shrink. For longer hauls, Gaudette said Microsoft is using PSM4 cabling with MTP connectors for longer hauls, but he added that the CWDM4 cables that Facebook is proposing with the relaxed specs is coming down in price where it is competitive. Here is how he ranked the options:

“CWDM is an interesting part and it will give us some flexibility to reuse infrastructure and perhaps fiber conduits and help alleviate fiber constraints,” Gaudette said. The longer haul LR4 and LR4-Lite cabling did not impress Microsoft.

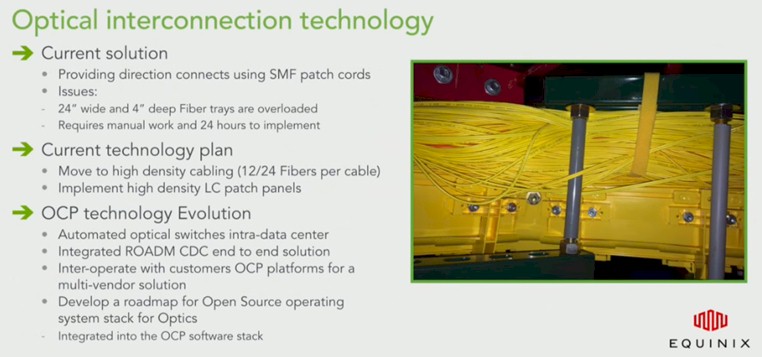

Ihab Tarazi, chief technology officer at Equinix, did not tap any particular cable as the inevitable future, but did say something interesting about what the company expected the industry to do and how it expected it to do it. Equinix has just joined the OCP and has also started up a parallel Telecom Infrastructure Project to drive standards among telcos and service providers.

“Our long-term solution, under the OCP, is to bring in automated optical switching and also ROADM CDC tech even beyond the datacenter so we can give the control to our customers to activate links between each other,” Tarazi explained. “We want to collaborate with everybody to figure out how we build that open source system using OCP optical components and allow it to reach into everybody’s cages.”

We have come a long way in only five years. It will be interesting to see what Google does here. But if Microsoft and Facebook get behind the CWDM4 standard, and Amazon Web Services quietly does as well, then it seems pretty obvious what kind of cabling enterprises and HPC shops will be using for linking rows and rooms in the datacenters.

Be the first to comment