All-flash array upstart Pure Storage has had a single target it has been aiming at since the company uncloaked from stealth mode back in the summer of 2011: Tier one disk storage in the datacenter. By Pure Storage’s estimates, enterprises worldwide have spent tens of billions of dollars buying 452,000 tier one disk arrays in the past four years, and if all of them were converted to the company’s new FlashArray//m all-flash storage, something on the order of 1.3 million racks burning on the order of 4 gigawatts of electricity could be eliminated from the world.

This would also make Pure Storage a tremendous amount of money. While such a wholesale and instantaneous conversion from disk to flash is not going to happen, there are indications that at least for some customers, moving to all-flash arrays makes sense for performance reasons or to curtail datacenter expansion and we could be looking at a wave of conversions that will sweep over datacenters a little more quickly than many might expect. The Moore’s Law increases in flash density are certainly helping the cause for solid state storage, as is the increasing sophistication of data reduction techniques that bring the cost of flash down to parity with raw enterprise-class disk arrays, which again is being enabled by the ever-increasing performance of disk controllers in the all-flash arrays.

PureStorage has been developing its “Platinum” flash arrays, which were launched this week as the FlashArray//m series, for the past two years precisely to intersect the capacity and performance curves for flash and CPU such that it can keep expanding the performance and capacity of its arrays in a fairly linear fashion. With the new machines, Pure Storage is addressing some of the complaints that enterprises in general have about flash arrays, mainly that they do not scale their capacity enough to take on the really big jobs.

Initially, because Pure Storage was focusing on peddling all-flash arrays to accelerate greenfield virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) setups or to give a boost to specific databases, scale did not matter as much. But as companies get more comfortable with all-flash storage and they see the performance, density, and power efficiency benefits, they reach a tipping point and want to start putting more and more applications on top of flash rather than disk storage. Scalability starts to matter. Midmarket companies have less storage, Brian Schwarz, director of product management at Pure Storage, tells The Next Platform, and it is easier and quicker for them to make this wholesale conversion – particularly because there is a relatively small set of people who make IT decisions.

“Our big customers, such as is in the oil and gas industry or among service providers, have a lot of sub-teams that make their own purchasing decisions, but obviously the aggregate amount of capacity that these customers are acquiring is much, much larger,” says Schwarz. “When customers get beyond one petabyte in a single array, they start worrying about too many eggs in one basket. We have one hyperscale customer that has several dozen flash arrays deployed, and each one is not going to be more than a half petabyte. I don’t think anyone wants one single storage array, and hyperscale customers in particular write their applications to scale out over lots of infrastructure pieces.”

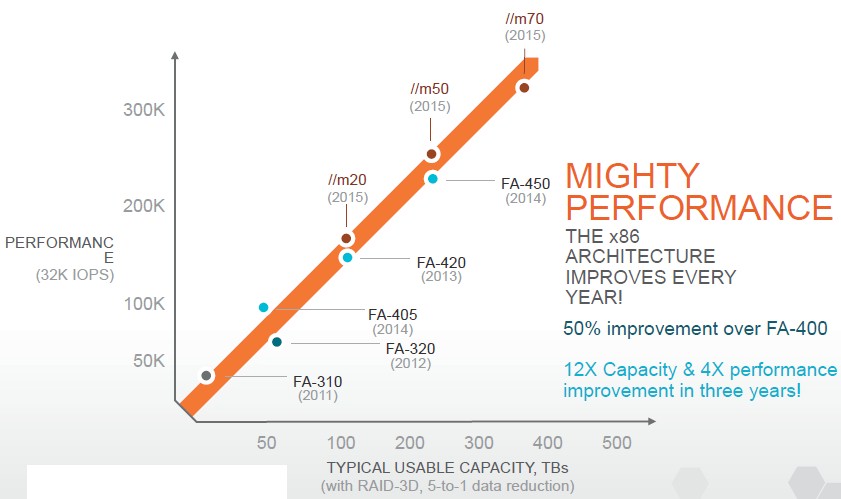

That said, the arrays do have to scale up, and with the FlashArray//m, Pure Storage is pushing up both the capacity and I/O performance of its arrays:

As you can see, each generation of Pure Storage arrays tends to overlay the existing products in terms of capacity with a boost for the high-end model while increasing the I/O operations per second (IOPS) of the controller and flash assemblies with each generation. Presumably customers want this balance of IOPS and capacity. By the way, Pure Storage has measured performance using 32 KB file sizes for several years now rather than much smaller 4 KB or 8 KB files that would boost the IOPS ratings, and Bill Cerreta, vice president of hardware engineering, says 32 KB files are the most common sizes that Pure Storage sees at actual customers. Hence that is why it tests the arrays with 32 KB file sizes.

In the three years since the first FlashArrays were generally available, Pure Storage has boosted the capacity of its arrays by a factor of 12X and the performance by a factor of 4X, measuring from bottom to top. And Pure Storage thinks it can keep on this curve to satisfy the needs of even the largest hyperscale and enterprise shops.

“We see a lot of headroom in the current architecture and our ability to scale with Moore’s Law,” says Cerreta. “A dual-controller scale-up array is a lot simpler than a scale-out clustered array. Until we run out of headroom, we want to keep it simple. We are going to double again next year and then double again the year after that, and we will have customers with hundreds of terabytes of capacity per rack unit, and it will get to the point where the failure domain will be more of an issue than capacity itself.”

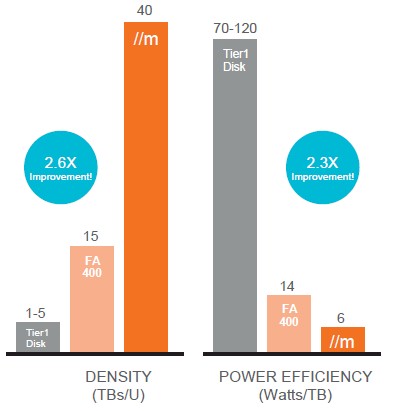

The gap between enterprise-class disk arrays and all-flash arrays when it comes to storage density and power efficiency just keeps getting larger:

In the chart above, the disk arrays are configured with 300 GB SAS drives, which are typical for such devices these days. At this point, the big issue is overcoming the fact that flash uses various kinds of software to de-dupe, compress, and protect data and that these techniques, which is what gets the cost of an all-flash array below the ballpark of $2.00 to $3.00 that it takes to acquire an enterprise disk array like EMC’s VMAX.

The FlashArray//m machines have a slightly different architecture than the FA400 series that they replace in the Pure Storage lineup. The main brains in the systems have been upgraded to the latest “Haswell-EP” Xeon E5-2600 processors from Intel, which offer a significant performance boost over earlier Xeons. The combined controllers have a total of 64 cores and 1 TB of main memory.

The arrays also use NV-RAM memory modules, which are comprised of DDR4 main memory backed by solid state memory; these link to the controllers through the NVM-Express (NVMe) protocol. NVMe is kind of like RDMA for storage in that it gets around the operating system driver stack to hook peripherals more directly with compute. These NV-RAM modules deliver 3.5 GB/sec of bandwidth, and each enclosure, which is designed to last from seven to ten years in the field, has two or four of these fast-memory modules. Pure Storage is not saying who its NV-RAM supplier is, but it is not SanDisk, Micron Technology, or Viking, according to Cerreta. The new flash modules in the Pure Storage arrays come in 512 GB, 1 TB, and 2 TB capacities – twice the prior generation – and use 12 Gb/sec SAS links to hook into the controllers. The base chassis has room for twenty of these flash modules. The controllers can have up to four expansion shelves in the FlashArray//m70, for a total effective capacity of 400 TB usable in an 11U setup, delivering 300,000 IOPS with average latency of under 1 millisecond.

The FlashArray//m series has been in beta testing with around fifty customers since the first quarter and will be in what Pure Storage calls “directed availability” for production workloads at a larger number of customers starting in July. Full availability for the machines is expected in the third quarter, likely in August.

Pure Storage is leveraging its Evergreen marketing program, which gives customers an automatic upgrade for controllers every three years as they increase their capacity. For customers that have recently bought the top-end FA-400 arrays from last year, Pure Storage will upgrade them to the new controllers if they buy an //m20 enclosure with at least 10 TB of incremental capacity; on an //m50 model, customers have to buy 20 TB of capacity to get the free controllers, and on the //m70 they have to buy 40 TB.

As part of the launch, Pure Storage is also rolling out its Pure1 management system for its storage, which is leveraging multiple petabytes of array performance and configuration information that it has gathered from customers to date. This telemetry, says Cerreta, was used to design the new product line, and customers can leverage the information about their own all-flash arrays (an array generates about 10,000 data points a day) to do real-time alerting, performance analysis, capacity planning, and proactive support. The Pure1 service, which is delivered under a SaaS model, is free with the arrays.

Pure Storage has raised a staggering $470 million in nine rounds of funding, and has become the key challenger to EMC when it comes to all-flash arrays. Last year, according to the analysis by Gartner, Pure Storage nearly quadrupled its sales to $276.3 million, nearly doubling its share of the market. IBM and NetApp grew more modestly with their respective FlashSystem and FAS arrays, and Hewlett-Packard grew by more than 10X to also become a contender with its 3PAR StoreServ all-flash arrays. EMC is still the company to beat, and it looks like Pure Storage is the only one that is in spitting distance at the moment.

Be the first to comment