What is stronger than the US dollar? The cloud computing division of online retailing giant Amazon, which would have long since been in a heap of trouble with Wall Street if it had not fired up its utility computing service back in March 2006. For the first time ever, Amazon has broken out sales and profit figures for Amazon Web Services, and the unit is larger – and more profitable – than many had expected.

In a conference call with Wall Street analysts going over its financial results for the first quarter of 2015, Amazon divulged that AWS had booked $1.57 billion in revenues across all of its infrastructure and platform services, which was a 49.1 percent increase over the year-ago period. The AWS business also had an operating profit of $265 million in the first quarter, up 8.2 percent from the first quarter of 2014. Amazon only provided five quarters of financial information for AWS in its presentation, and that shows that the company has not had steady sequential revenue growth but has grown both revenues and operating profit for AWS year-on-year in all of those five quarters.

In some ways, AWS is an unusual IT supplier in that customers can and do turn off capacity on a whim, and also fire it up on a whim. The idea has always been to amortize the investment in IT infrastructure over as many customers as possible and drive up the utilization on the machines with aggressive spot pricing and discounted reserved instances. Generally speaking, it seems to be working really well.

Amazon revealed earlier this month that it has over 1 million active customers. Their usage is all over the map individually, but collectively they smooth out a relatively tidy exponential curve. To give an idea of growth, Andy Jassy, senior vice president in charge of the cloud subsidiary of the online retailing giant, gave out some relative metrics for the usage on the EC2 compute and S3 storage services for the fourth quarter. In terms of normalized instance hours per week (taking out Amazon’s own use for its retail operations), EC2 grew by 93 percent in the fourth quarter of 2014. Usage on S3, as measured by data flowing into and out of the object storage, rose by 102 percent in the quarter. (Amazon has dozens of other services, so this is not necessarily a good overall proxy for capacity usage on the AWS cloud. But this is the data we have.)

As we learned today, Amazon’s revenue growth was only 35.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2014, and coincidentally its operating profit growth matched that rate, presumably because the company was not doing heavy investments in new datacenters and gear as it seems to be doing in the second and third quarters each year if the limited operating income data is any clue. (Price cuts, of which Amazon has had 48 since its inception, also play a big role in curbing revenue growth and operating income.)

If you look at the trailing twelve month figures that Amazon has always used for its retail operations, then AWS has booked $5.16 billion in sales and brought $680 million of that to the middle line as operating income. This is not the kind of margin that you would expect from an IT supplier in a cut-throat market, but the convenience of cloud computing and the increasing sophistication of AWS offerings allow it to command a premium. This is also not the level of margins that legacy IT software suppliers who peddle operating systems, middleware, databases, and application software, but it is also not nearly as miserly as the profits that server and storage makers sometimes have to live with – like the ones who sell stuff to AWS, in fact, who have it worse among all the IT hardware suppliers, we presume, when it comes to profits.

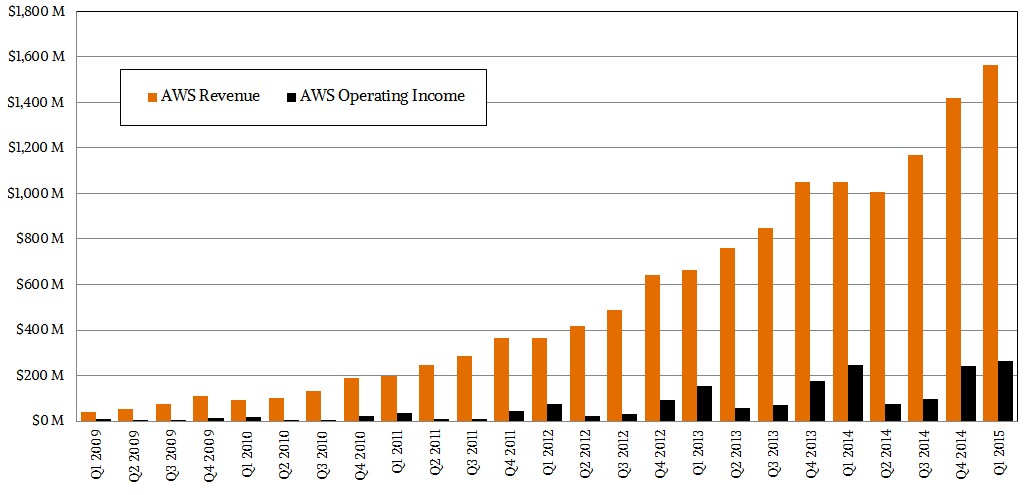

Amazon has been putting sales of AWS into the Other category since it was started up in 2006, and for fun we took the historical data from that Others category and estimated the revenue and operating income going back to the beginning. Here is what it looks like:

Our assumptions in this model are that AWS ramped to dominate the Others category, but it did not do so immediately. We also assume that AWS was modestly under water at first, but not hugely so because it was really just burning off excess IT capacity from the Amazon retail operations. With all of those caveats, we reckon that AWS has raked in $13.6 billion in revenues over its lifetime, and about $1.8 billion in operating income. If you back all of this revenue and net income out of the overall Amazon numbers, then Amazon would not be doing all that well and it is very likely that Wall Street would have hammered Amazon stock down quite a bit. So in a way, AWS didn’t just transform the IT operations of a tech-heavy online retailer, but it gives Amazon a means to keep pushing down prices and expanding into new markets.

AWS Has To Beat Moore’s Law – Every Year

If you drill down into the books, AWS had a whopping $6.98 billion in assets, which is the combination of property, equipment, and accounts receivable, through the end of December, up 81.8 percent from the $3.84 billion in assets it had as 2013 came to a close. The value of property and equipment (presumably all depreciated to a net present value) stood at just a hair over $6 billion, up 85.8 percent from the year-ago period. Of this value, $4.3 billion of that was net-new investment in property and equipment for all of 2014 – again, nearly double that of the year ago period. This all stands to reason, with capacity for core services more or less doubling every eighteen months or so.

The fun bit of this is that revenues are only growing roughly at half the rate of capacity and investment rates. Now you can understand the relentless pursuit of efficiency that the hyperscalers and public cloud providers have. The only way this is sustainable is to wring more and more work out of servers, storage, networks, and datacenters. AWS cannot just rely on the bumps in capacity for CPUs, memory, disks, and flash that normal IT suppliers would offer at their own pace – and with their own profits. AWS would not be a profitable business, and parent company Amazon can ill afford this. In the first quarter, Amazon had $22.72 billion in sales and an operating income of $255 million and a net loss of $57 million after allocating stock-based compensation, income taxes, and other expenses. Take out AWS, and the rest of the company is under water. Not ridiculously so, mind you. But enough to make Amazon shareholders a whole lot less rich. As it is, they just got a bit richer because now we know that AWS is profitable.

In the past, Jassy has said that that in the fullness of time, Amazon believes that AWS can grow as large as Amazon itself, which booked around $84.3 billion in sales not including AWS in 2014. This sounds provocative and even possible, but this will still be exceedingly difficult to accomplish. A good recession could help AWS along, and one will likely happen in the next several years because recessions do happen.

But if you look at Amazon revenues on an annualized basis (and assuming our model is not far off), growth is high but decelerating from the early years. The Next Platform services layered on top of AWS could yield a step function in growth like in the early years, when AWS was selling mostly raw infrastructure services. If the growth rate in revenues stayed steady for AWS from here on out, it would take until around the middle of 2023 for AWS to hit the $85 billion mark. Revenue growth may have accelerated in the first quarter, as AWS said on the call, but it has no doubt slowed down in recent years as happens in all new markets. It definitely slowed in the first three quarters of 2014.

If it takes somewhere between 2.6 million and 5.4 million servers to provide capacity for more than 1 million users and to generate $4.6 billion in revenues a year (as AWS did in 2014), will the infrastructure and customer base, and depth of service, have to scale by nearly a factor of 20 to reach that revenue aspiration? If Moore’s Law doesn’t run completely out of gas, Amazon just might be able to keep the AWS system footprint growing by a few multiples (maybe 5X) over that time as its customer base and services expand by 20X.

It will be very interesting to see how AWS engineers this.

Some good info here but this idea of AWS “burning off excess IT capacity from the Amazon retail business” is pure fiction. Never happened. There were two completely separate operations from the very beginning.

Very interesting – but as usual the devil is in the details.

Reported AWS profitability may depend A LOT on the speed of depreciation of 3-5 billion $ of computers and networking etc – which also may be lower or higher than depreciation determined by technology changes and competitive pressure.

Also, 6B$ of property/equipment seems inconsistent with your estimate of 2.6-5.4 million servers (my guess is that real number may be between 1 and 2 million servers).

I love your coverage on technology, but not so much when it comes to economics.

AWS revenues run 6-30x times the cost of a server. This is not a cost play, but simply superior revenue management. Yes, it’s nice to get a server for $1000 cheaper than the average big IT shop, but AWS is not getting some sweetheart deal from Intel for chips.

What matters is the revenue-to-cost ratio for infrastructure and how infrastructure turnover drives capacity and revenue growth. So chip productivity is a far bigger driver of value for AWS than cheaper servers. Intel has no need to discount chips for AWS beyond what they already do for other big buyers.

Since server cost (amortization schedule) has little to do with driving margin, if AWS is faced with adding another data center, or postpone or avoid it by refreshing servers faster (e.g., shorter than 3 years), it often makes financial sense refresh faster. In fact, the faster AWS refreshes servers – with better servers – the lower their average inventory balance. AWS first priority is to maximize revenue per rack, not minimize cost per rack. They don’t need the cheapest server. That’s why AWS buys Intel’s higher end chips, not low-end cheapies.

The business model rests with maintaing higher margins with better softwareware based services. The lock-in is AWS tooling.

Owning hardware is actually a big risk factor; it’s both perishable and decaying inventorying. Turning over hardware as fast as economically possible is the goal – not scale purchasing per se. The latter is mostly a myth. Now to accomplish the right level of inventory turnover — that takes some advanced mathematics to accomplish (think how airlines work) and AWS is not sharing that info.