IBM finalized the spinoff of its System x X86 server business to Lenovo Group back in October, and the first quarter of 2015 is the first glimpse that we have of a Big Blue that is focused solely on its Power Systems and System z mainframes. The good news for IBM is that the new System z13 mainframes, which were announced in January have taken off strongly, and sales of Power Systems servers have stabilized thanks to the Power8 ramp and a more aggressive expansion into the scale-out Linux market that is being spearheaded by the OpenPower Foundation.

We had been expecting for IBM to reclassify its financial results in the wake of the System x and Microelectronics division spinoffs. Such a reclassification would emphasize that the company was an enterprise systems supplier and stacking up all the elements of that business – servers, storage, operating systems, middleware, database software, and maintenance for the whole shebang – and carving them out separately from the software and services it peddles for other people’s iron and clouds would show how large and profitable the true IBM systems business was. The company has not done this, but could once all of the year-on-year compares do not have System x sales data in them. Such accounting would be an honest reflection of IBM’s actual systems business. IBM’s System and Technology Group and its Software Group were never really separate entities, and ditto three times over for its Global Services behemoth. Then again, it may not want to crow too loudly about how much money it is extracting from these hard and soft wares.

System hardware accounted for $1.66 billion in revenues in the quarter, and at constant currency (which was anything but that on a global basis for Big Blue in the first quarter) this group had 30 percent growth in the quarter. Combined, System z mainframe and Power Systems sales came to $1.15 billion in revenues, which may not seem like a lot to those of us who can remember Big Blue bringing in more than $1 billion each for the System z, System x, and Power Systems lines in a great quarter. Those days are gone, of course. But that does not mean that IBM can’t still have a profitable high-end hardware business in its own right and that a true systems business, with all of its software and services properly allocated, would not be even more profitable. (You might be wondering why we at The Next Platform care about IBM mainframes. The short answer is that the System/360 mainframe and its follow-ons though the past five decades were what we would consider the first true platform, and so by design.)

In a conference call with Wall Street analysts, IBM CFO Martin Schroeter said that even though the System z mainframes had only been shipping since the middle of March, the company had been working with over 60 customers to design the systems and inform IBM’s pricing for them, and that it had been working since their launch in January to build the sales pipeline and actually sell and build machines so they could be shipped and therefore have their revenue booked. (If it ain’t on a truck out for delivery, Big Blue can’t book it.) The amount of aggregate processing capacity that IBM shipped across its mainframe sales, as measured in a mythical metric called MIPS that no longer bears any relationship to millions of instructions per second, rose by 95 percent in the quarter, but mainframe revenues rose by 130 percent (at constant currency) and more than doubled as reported in the figured converted to US dollars that go into IBM’s financial reports. Schroeter said IBM shipped more mainframes and had the fastest growth in revenues that it has seen in more than a decade in the mainframe line. IBM attributes this to its customers adding fraud detection, analytics, and mobile workloads to their big iron. The interesting bit is that if you do the math, then mainframe average selling prices are on the rise, bucking the Moore’s Law trend.

IBM was not specific about how the Power Systems business was doing, other than to say that it had gained market share in the declining Unix-based system business (which it has been doing for more than a decade), and that is not as much to write home about these days even if it does fund the future development of Power-based systems. IBM said that the uptake of its two-socket Power8 machines for scale-out clusters was picking up a little steam and it mentioned its expansion with a heavy push for Linux on these boxes, but the company did not – and probably will not – quantify this. It will be interesting how IBM tracks its own Power-Linux sales against and in concert with its OpenPower partners in the coming quarters and years. IBM will have both licensing revenues and system revenues.

The other thing that Schroeter said relating to Power Systems was that the remaining Power8-based systems would launch toward the end of this quarter. IBM is expected to deliver a four-socket Power8 system, which it has not yet done, and also needs to fully flesh out the high-end of its Power E880 systems, which will extend to sixteen processor sockets and up to 16 TB of main memory in a single NUMA system image. The top-end Power E880 machine will have up to 128 cores running at an as-yet-unknown clock speed using twelve-core Power8 processors, yielding more performance than a Power7-based Power 795 machine with 32 sockets and up to 256 cores. The fact that IBM did not push the Power E880 up to 32 sockets tells you that the demand for an even larger machine is not sufficient to justify the engineering effort.

IBM’s storage business accounted for $465 million in the quarter, down 2 percent, and Schroeter said that while IBM’s FlashSystem all-flash arrays did well, the continued decline in high-end disk arrays was a drag on the overall business. IBM sold another $50 million in other hardware products, and it is not clear what these are but it is very likely rebadged Flex System and networking gear from Lenovo.

Rounding out IBM’s system business, its Software Group posted sales of $5.2 billion, down 2 percent at constant currency but off 8 percent as reported. (The US dollar keeps strengthening against other currencies, and the gap between the greenback and the other currencies of the world was even larger than expected in the first quarter.) Operating systems accounted for 8 percent of Software Group’s sales, and on the mainframe, this software is basically like a monthly annuity for Big Blue. The bulk of IBM’s software sales are for databases, development tools, security and system management software, and middleware as well as a bunch of software its sells for workforce management and collaboration. This “key branded middleware,” as IBM calls the WebSphere, DB2, Tivoli, Lotus, and Rational lines, accounted for $3.48 billion, while other middleware – which all runs on IBM System z and Power Systems machinery – accounted for another $884 million.

IBM’s Real Systems Business

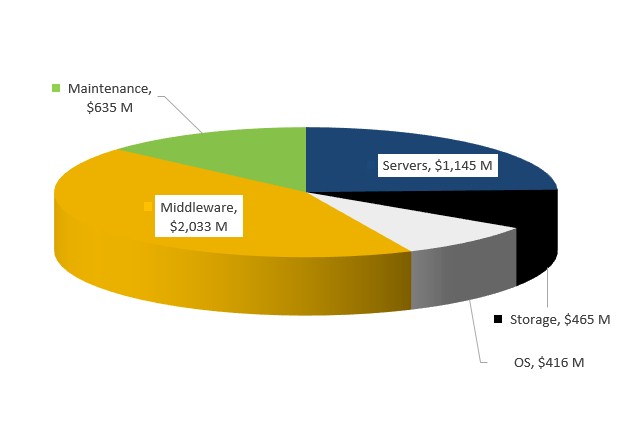

Let’s assume that a third of the revenue for that key branded middleware came off IBM’s System z and Power Systems lines, a third came from System x iron, and another third came from iron without an IBM brand. That yields an IBM systems business with $1.15 billion in servers, $465 million in storage, $416 million in operating systems, and $2 billion in other systems software. IBM had another $1.59 billion in maintenance for hardware and software, and if you assume about 40 percent of that is for its Power Systems and System z hardware and the software running on it, that’s another $635 million. Let’s ignore the systems integration, consulting, and outsourcing of IBM’s systems for a minute. Add that all up – hardware, systems software, and maintenance on Power and z iron – and you get a $4.7 billion business that probably has an operating profit that is somewhere on the order 50 percent. (In the 30s range for the hardware and in the 90s range for some of that mainframe software.)

This is not a bad business on which to build. The question is whether IBM will be able to build a Power Systems business that can sell a few billion dollars a year in Linux clusters. And there is probably a few more billion in revenues coming from IBM systems that are hosted or outsourced by Global Services.

To put this another way, had the mainframe cycle not come around and had IBM not stabilized its Power Systems business, the first quarter would have been worse than it was. As reported, IBM’s revenues were down 11.9 percent to $19.59 billion, and net income was down 2.4 percent to $2.33 billion. IBM’s executives can explain that two thirds of that decline was from currency effects and one third was from divested businesses in the compare, and they can talk all they want about the cloud business having a run rate of $7.7 billion, up 75 percent at constant currency and up 60 percent as reported, and that sales in their strategic initiatives of analytics, mobile, and social growing 30 percent. But what Wall Street and customers alike want to see is IBM building big systems and selling lots of them – not making excuses or smudging the numbers. (What exactly is in that cloud number, for instance?) IBM should probably do away with the product categories it has been using since the dot-com boom and get back to presenting itself as what it really is: A systems company that also happens to sell some stuff for other people’s iron.

Be the first to comment