The IT industry likes drama perhaps a bit more than is warranted by what actually goes on in the datacenters of the world. We are always spoiling for a good fight between rival technologies because the clash results in competition, which drives technologies forward and prices down.

Ultimately, organizations have to pick some kind of foundation for their modern infrastructure, and OpenStack, the cloud controller spawned from NASA and Rackspace Hosting nearly six years ago, is a growing and vibrant community that, despite the advent of Docker containers and the rise of Mesos and Kubernetes as an alternative substrate for virtualized infrastructure, continues to see market uptake and companies moving from proofs of concept to production.

It is fun to pit OpenStack against Mesos and Kubernetes, as we have done here at The Next Platform from time to time, and not just because it is an academic thought experiment. Ultimately, way down under the applications and the layers of abstraction that hide the real servers, switches, and storage that comprise clusters from those applications, there has to be something that is ultimately in control. So long as OpenStack continues to evolve and, more importantly, continues to work on fit and finish and other operational aspects of the cloud controller and its adjacent projects, then it will get its adherents because for many

The fact is, IT infrastructure is always a mix of old and new. And Jonathan Bryce, a former Racker who has been executive director of the OpenStack Foundation for the past several years, did not mince words in describing the situation during his opening keynote at the OpenStack Summit today.

“We are in the middle of a disruption and OpenStack is part of that, but it goes beyond OpenStack, it goes beyond cloud computing, and it really gets to how business is being done,” Bryce said in his opening keynote. “One of the things we see is that our IT environments are becoming increasingly diverse. When was the last time you had to manage fewer technologies in your IT environment? It doesn’t happen, and that is the promise whenever a new technology or a new company comes along. They are going to give you the one thing you need, they are going to make your life simpler. I hate to break it to you, but we have been lying to you all these years when we say that. All of those technologies end up being additive. They are new, but you have to maintain the new capabilities.”

In times of disruption, as we are concurrently absorbing across business sectors and within the IT organization itself, you need to have some kind of coherent strategy, and for many organizations, the OpenStack fabric for compute, storage, and networking and its API management stack has become the preferred foundation.

Not everyone agrees with this approach, and Bryce’s point is that they don’t have to, and it is perhaps illustrative that Intel is working with Kubernetes distributor CoreOS and OpenStack distributor Mirantis to get OpenStack running on top of Kubernetes for those organizations that want to run both virtualized and containerized applications. There are other organizations that will want to flip that stack and deploy Kubernetes on top of OpenStack – LivePerson will be talking about its own such implementation later in the OpenStack Summit and we have already profiled how eBay is doing something similar, and Time Warner will be talking about how it is running Mesos on top of OpenStack as well.

As far as the OpenStack community is concerned, companies will use a mix of technologies, and Mark Collier, chief operating officer at the OpenStack Foundation and a former Racker and colleague of Bryce, will be talking tomorrow about how billions of connected devices will drive a need for data processing powered by billions of cores and hundreds of millions of servers, with a mix of bare metal, virtualized, and containerized workloads. And if you believe that thesis, then something, way down underneath it all, will have to be able to be the main controller for those three different types of compute surfaces and their networking and storage, and obviously the OpenStack community wants its wares to be that main controller.

Lucky Number Thirteen

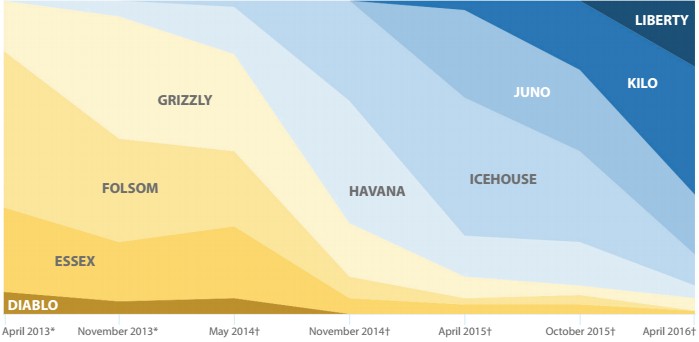

The OpenStack Summit comes just two weeks after the “Mitaka” release of OpenStack debuted. This is the thirteenth such bundle of the cloud controller since the “Austin” release, which was not really production grade at all, came out in October 2010. The “Diablo” release a year later was closer to being truly useful, and over the years as components have been added and the software stabilized and refined, it has become something more akin to a cloud operating system that enterprises without the sophisticated software engineering staffs of cloud builders or HPC centers can deploy. Red Hat, Canonical, and Mirantis have all done their parts to build OpenStack platforms that have commercial-grade support and that are much easier to install than grabbing the open source components.

With the Mitaka release, there are no big changes to the core components that debuted last fall with the “Liberty” release, and that is not surprising because for the past few years the OpenStack community has been more focused on making the software usable rather than on scalability and performance, which were, like Linux in its early days, a primary issue for OpenStack a few years back. This is a necessary stage for any open source project that hopes to see broad adoption, but we must admit, it is less exciting in some ways than watching the core software first mature.

Instead of looking at how many cores or nodes OpenStack can scale to, the metrics to watch are about adoption by and contributions from the community of developers that are creating the code. Over 2,300 developers from 345 organizations around the world contributed to the Mitaka release, which is a far cry from the early days when NASA and Rackspace dominated the code. Red Hat, which is also a big contributor to the OpenStack effort, would not even participate until the foundation was set up and Rackspace backed off a bit. It all worked out in the end, if perhaps not as fast as people outside of Rackspace had wanted in the early days.

As for users, which is what really counts in the end, Bryce said that half of the Fortune 100 was running OpenStack, and without giving a number, he added that “more public clouds than ever before” were running OpenStack. We not that he did not say half of the Fortune 500 or half of the Global 2000, by the way. OpenStack is something for companies that want an open source alternative to VMware’s ESXi hypervisor and vSphere and vCloud management tools and for a lot of enterprises, it has taken them years to get virtualized and they are only now looking at how they might orchestrate their virtual infrastructure and turn it into clouds.

No one knows for sure how many companies have deployed OpenStack, however, because any self-supporting organization can just download the code and go. (We got a sense of how Mirantis sees the OpenStack installed base last fall, which was revealing.) Based on the semi-annual OpenStack user surveys that the community does, Bryce said that it has profiled a couple thousand OpenStack installations that comprise millions of cores. This is about the same size base for the Hadoop data analytics market and for the core HPC community, which are analogous and sometimes overlapping. (Perhaps moreso in the future.)

Of the more than 1,000 OpenStack users who were polled in the April 2016 survey that was timed to coincide with this summit in Austin, over 65 percent of the OpenStack clouds were deployed in production, compared to just shy of half a year ago and a third two years ago.

Because OpenStack is still fairly young as a platform, users tend to stay current, much as was the case in the early days of Linux when the feature set was evolving fast and, frankly, the software was not yet on par with Unix alternatives and was not as familiar as Windows and therefore was of limited appeal to all but the most tech savvy of IT organizations.

The commercial Linux distributors and the OpenStack community have synchronized their development cycles in the past few years, with OpenStack following a cadence of releases in April and October that Linux distributor Canonical has used for its Ubuntu Server for as long as we can remember. While no one is talking about this yet, it is possible that at some point OpenStack will have a six month cadence for regular releases and then a “long term support” cycle with years between releases for those who do not want to change their technology as frequently. We think OpenStack is probably not mature enough for this yet. But the day will come and the community and commercial distributors will have to decide what to do.

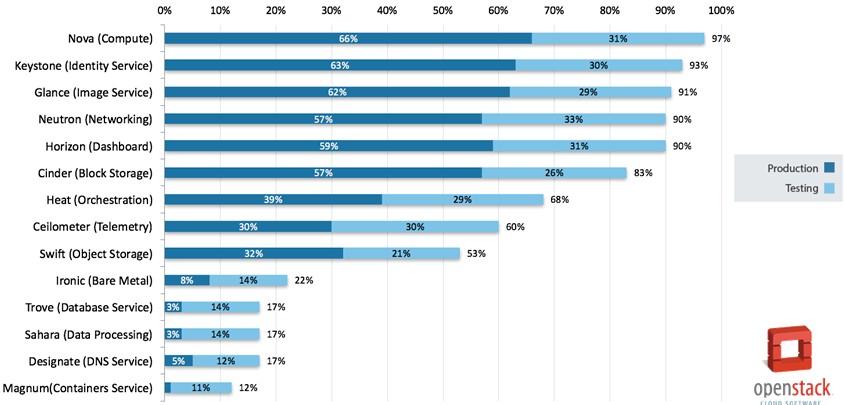

The latest survey out of the OpenStack community shows that the core compute and networking services as well as management tools for OpenStack are widely deployed, but that the Swift object storage that Rackspace contributed to the effort way back when is not as widely used as the Nova compute or Neutron networking components. The reason is simple: there are alternative object storage projects that are compatible with OpenStack but that are not part of the community, such as Ceph.

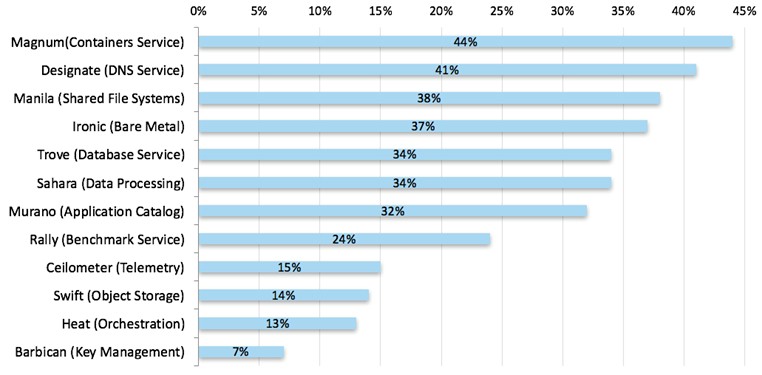

The Ironic bare metal provisioning add-on for OpenStack is seeing some uptake, and customers are just starting to play around with the Magnum container service plug-in, which we profiled here. But as you can see in the chart below, among the OpenStack shops surveyed – and with more than 1,000 users polled in a base that might have maybe 1,500 to 2,500 total users it is surely statistically significant – the Magnum and Ironic projects are among the most popular projects of interest.

Speaking generally, 70 percent of OpenStack shops said containers were of interest, and the split between the interest levels suggests that tools other than Magnum are being looked at. Although this data was not presented in the public report, of those OpenStackers that have deployed application orchestration and management tools for containerized apps in production, 27 percent say they have deployed Kubernetes, with Cloud Foundry being used by 16 percent, Mesos by 11 percent, OpenShift by 10 percent, and others (including Docker Swarm and Cloudify) all getting tiny slices that add up to 25 percent collectively.

About half of the shops said that bare metal provisioning was also of interest, with about the same being interested in software defined networking and network function virtualization, 44 percent interested in hybrid cloud, and 29 percent wanting to mesh hardware accelerators such as FPGAs and GPUs with their cloudy infrastructure and have such resources allocated by OpenStack.

Be the first to comment