Cybersecurity has never been easy. As the amount of business being done on the internet has grown, enterprises, smaller businesses, HPC institutions and other organizations have had to develop and embrace technologies designed to protect mission-critical data and applications from an increasingly sophisticated underworld of hackers, nation-states and other cyber-criminals. For a long time, that has meant encircling the datacenter – home to all those workloads and data – with firewalls designed to keep the bad actors out and connecting remote offices to the datacenter via secure MPLS networks.

The rise of the cloud, emergence of the rapidly expanding Internet of Things (IoT) and now the edge has changed the security equation. Applications and data are no longer sequestered in on-premises core datacenters but can be accessed from multiple places by myriad devices, with data ping-ponging between datacenters, the cloud (and between clouds) and the edge. Simply putting up a corporate firewall no longer works. The applications and data are free-range.

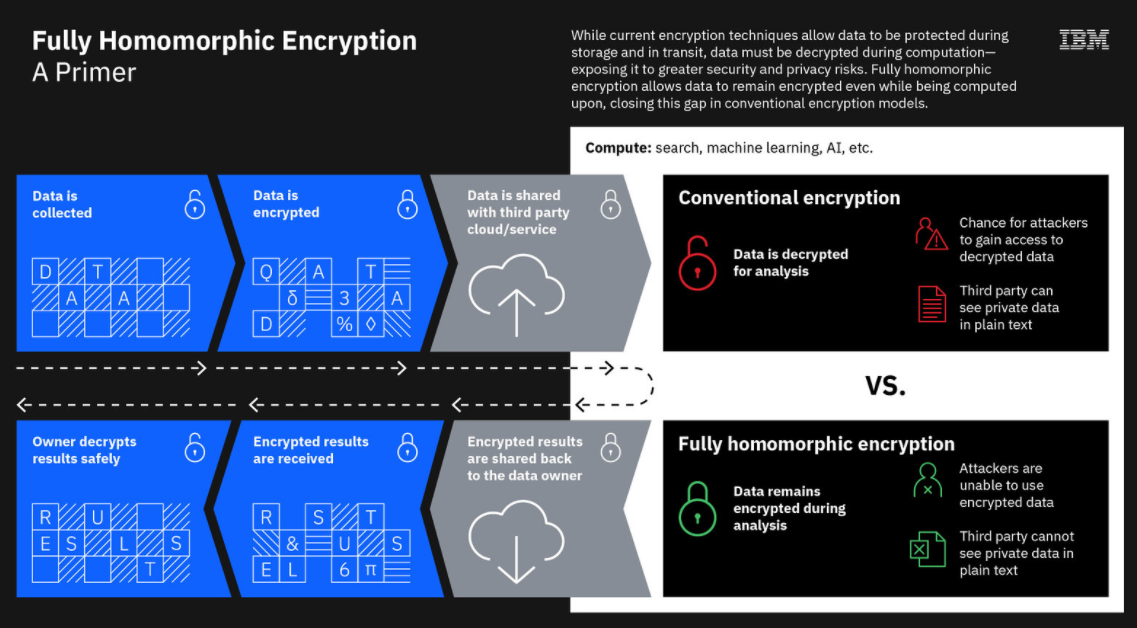

Encryption, always a critical tool, has only increased in importance in recent years. Done right, encryption might not stop cyber-criminals from getting ahold of the data, but it can protect the data and make it useless to the bad guys. Right now, enterprises can encrypt data while it’s sitting in storage and while it’s in transit from one place to another. However, a glaring weak spot is when data is being processed, analyzed and otherwise used by applications. At that point it needs to be unencrypted and is more vulnerable to cyberattacks.

This is where the emerging technology of fully homomorphic encryption comes in. FHE enables data to remain encrypted even as organizations work on it in the cloud or in third-party environments. Once the work is done on the data, the results are decrypted and corrected.

FHE has been talked about for almost four decades, though it wasn’t until 2009 that it was first demonstrated. Now vendors are pushing to commercialize FHE and get it out to enterprises that are seeing their migration to the cloud accelerating due to the COVID-19 pandemic. IBM, which last year ran FHE field trials and released a FHE toolkit for MacOS and iOS – with Linux and Android following – is now offering an FHE service on the IBM Cloud. Microsoft’s SEAL is powered by open-source FHE technology and includes encryption libraries organization can use to run computations on encrypted data.

Other vendors in the space include smaller players like Enveil (which uses FHE in its ZeroReveal solution, ShieldIO and Duality Technologies.

Now Intel, which for years has been bringing more security capabilities onto its silicon, is getting into the FHE arena. The world’s largest chip maker this week announced it is one of several research teams tapped by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to work – in conjunction with Microsoft – in creating an ASIC for FHE. The accelerator will be used in DARPA’s Data Protection in Virtual Environments (DPRIVE), a program aimed at creating the hardware necessary to reduce the compute power and time currently needed to run FHE operations. Intel is part of that project, which this week announced four research teams whose goal will be to create an FHE accelerator along with an accompanying software stack that will make the speed of FHE calculations more in line with similar operations on unencrypted data.

Intel will lead one of those teams. The other three will be headed by Duality, software maker Galois and SRI International, a nonprofit scientific research institute based in Menlo Park, Calif. In announcing the DRPIVE program, DARPA program manager Tom Rondeau said that organizations are struggling to “trust the technologies and standards in place that are designed to protect critical data. Advances in quantum computing are raising questions about the durability of some of the most advanced data protection technologies, while concerns are being raised about the collection, misuse, and handling of personal information by organizations and institutions. These challenges underscore an urgent need to explore new secure computing models that can mitigate risk whether data is at-rest, in-transit, or in use.”

Rosario Cammarota, principal engineer at Intel Labs and principal investigator for the DPRIVE program, called fully homomorphic encryption the “holy grail in the quest to keep data secure while in use,” adding that the inability to process and run calculations on encrypted data “frequently inhibits our ability to fully share and extract the maximum value out of data.”

The push for FHE is important because not only is the computing environment changing – and making cybersecurity even more difficult – and emerging technologies like quantum computing are threatening current technologies, but the amount of data being generated is growing exponentially – IDC analysts are predicting as much as 175 zettabytes of data will be created in 2025 – and the growing regulatory environment around data security and privacy through such laws as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA).

FHE can be an important technology in addressing data protection issues, but currently a computation on a standard laptop on unencrypted data that could be run in a millisecond would takes weeks on a conventional server running FHE technology, DARPA’s Rondeau noted. The federal organization is hoping that the DPRIVE research teams will be able to develop accelerators and software that will reduce that overhead and drive down the processing time from weeks to seconds or milliseconds.

Such accelerator architectures that are programmable and scalable will make FHE a more viable tool for enterprises to protect their corporate data. In its partnership with Intel in the DPRIVE program, Microsoft brings its experience not only in working with FHE but also as a top-tier cloud provider via Azure and its winning of the $10 billion Joint Enterprise Defense Initiative (JEDI) contract that essentially would involve creating a cloud computing platform for the federal government that would act as an umbrella for Defense Department cloud operations. It also would offer a broader general-purpose cloud platform.

Microsoft would help lead the commercial adoption of FHE technology once it’s developed through testing in its cloud environment, including Azure and JEDI. However, Microsoft’s grasp on the JEDI contract continues to be controversial. Oracle and IBM had been rejected early by the DoD and Oracle sued – and lost – alleging improprieties in the contract award process that favored Microsoft and Amazon Web Services.

Microsoft was awarded the contract in 2019 and AWS sued. All the lawsuits have pushed back the timeline for JEDI, which was expected to be implemented more than a year ago. Reports surfacing this month indicate that the DoD may rescind Microsoft’s contract if a federal judge doesn’t dismiss AWS’ lawsuit and allows litigation to continue.

The DPRIVE program is expected to span multiple phases over multiple years, starting with the design, development and verification of the IP blocks that will be included into the system-on-a-chip (SoC) and software stack, according to Intel. The chip maker said it will assess its work using pre-established performance targets on artificial intelligence training and inference workloads using FHE at scale. Intel and Microsoft also will work with standards bodies to help develop FHE standards.

Along with the accelerator architectures, the DPRIVE program will also look at using different native word sizes with FHE, according to DARPA. Most CPUs currently are based on 64-bit words, which form the foundation of processor designs. For FHE, word size impacts the signal-to-noise ratio of how encrypted data is both stored and processed and the error generated each time and FHE calculation is processed, the organization said. The research teams will evaluate a range of approaches that address word sizes, from 64 bits to thousands of bits.

So did darpa sell a block of ips?bin being hacked by an ip registrar to darpa in 2013. 192.168.10.203. Crashed 3 laptops. Ddossed for a week. Isp and cell messed with. DAta stolen..