The profit pools in datacenter infrastructure are a bit like oases in the desert: There are a lot of miles between them, and some of them turn out to be mirages.

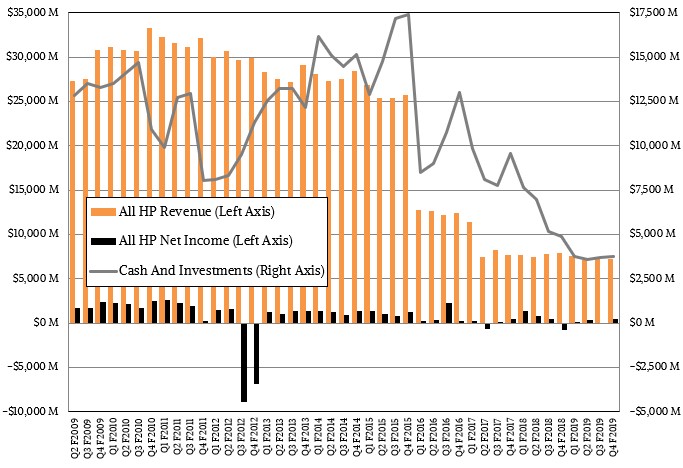

Over the past several decades, the various forms of Hewlett Packard have found and leverage profit pools – it is really amazing just how much of the company’s success came from LaserJet ink and how priting’s profits allowed it to make the investments to broaden its systems business from a small line of proprietary machines to a big player in scientific workstations (the original Apollo systems, thanks to an acquisition) to an innovator in RISC/Unix systems for the datacenter. The cash flows from its revenue streams gave it the chance to eat Compaq/Digital/Tandem as well as EDS to create an alternative to the IBM behemoth in the datacenter in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But in more recent years, Hewlett Packard has been paring itself down to the bare enterprise essentials and walked away from unprofitable hyperscaler, cloud builder, and service provider system sales and sold off most of its services and software businesses to boot.

It remains to be seen if the resulting Hewlett Packard Enterprise can be more profitable than the prior incarnations, but a few things are pretty certain. One is that even though it is tough make a profit in the enterprise IT segment, it is a hell of a lot harder in other segments (including the hyperscalers, cloud builder, and service provider segments mentioned above) as well as the adjacent market for high performance computing systems exemplified by parts of the Compaq and HP businesses in days gone by as well as in the businesses of acquisitions SGI and Cray.

It is interesting to us that HPE is doubling down on HPC, and therefore AI, just as it is winding down its hyperscale, cloud, and service provider system business. There is, presumably, less competition in HPC and AI, and while many of the deals many not be terribly profitable, the technologies developed for HPC and AI can scale down to enterprise, and be sold at a higher profit margin in many smaller chunks. Hyperscale does not scale down very, and only makes sense when operating with millions of servers. And the ODMs and more aggressive OEMs (like Dell and Lenovo) fight viciously to maintain their accounts. They also have PC businesses that give them tremendous pricing leverage with component suppliers – something that HPE gave up when it split systems from PCs and printers several years ago. This may have unlocked some short-term value, but it didn’t do HPE any favors when flash and memory prices went nuts two years ago.

Former chairman and chief executive officer Meg Whitman and current chairman and chief executive officer Antonio Neri believed that a pared down, more focused HPE could deliver the profits that have eluded the larger versions of Hewlett Packard. We are more cynical than that, and think that it is very hard to find any reliable profit pool in the datacenter. The hyperscalers and cloud builders have forever changed the IT climate, speeding up cycles and raising the competitive temperature, and it is they, not large enterprises, that set the pace. They turn their scale into their profits as they turn around and sell infrastructure against companies like HPE, Dell, and Lenovo, in essence returning us to the service bureau days of the 1960s and 1970s.

We will probably regret that in the long run. But at least that swing from on premises to cloud makes a lot of the core infrastructure someone else’s problem, so there is that.

In the meantime, HPE is doing a pretty good job holding back the tide and many businesses are not convinced that they should unplug everything and run all of their applications – and hence the real muscle and brains of their businesses – on Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, IBM Cloud, Alibaba, or Tencent. Yes, about a third of the money that gets spent on infrastructure is going into the public cloud, according to the latest data from IDC, but there is another 20 percent that is being spent on private clouds and the remaining 50 percent is being spent on traditional bare metal or virtualized infrastructure. At this rate it will take another decade ore two to eliminate on premises infrastructure, and we are not even sure that will ever happen for lots of reasons, ranging from cost to pride to security to data sovereignty.

It is against this backdrop that we ponder the fourth quarter of fiscal 2019, which ended in October and which HPE just announced. In the period, HPE’s sales (not including much of a contribution from Cray, which had only been on the books for a few weeks) fell by 7 percent to $7.22 billion, but it swung from a $757 million loss in the year ago period to a $480 million net gain this time around. There were plenty of restructuring costs and spinoff costs in the Q4 fiscal 2018 numbers, so the comparison is a bit weird, and while as Neri was saying to Wall Street that HPE has held revenues steady around the $7.2 billion mark in the three most recent quarters, the company’s profits and sometimes losses are bouncing around still.

On the systems front, Tarek Robbiati, chief financial officer at HPE, said on the call with Wall Street that server shipments were up sequentially if you take out the effect of local currencies being converted back to US dollars and the exit from selling machines to Tier 1 service providers, a term that is much broader, in concept, than our more specific characterization of cloud builders, hyperscalers, and service providers of other kinds. HPE had a pretty sizeable business selling to Tier 1s, which is distinct from the top eight or so hyperscalers and cloud builders, which we presume we could call Tier 0. It had a piece of the Microsoft action for some time, but that was about it. Dell had a much bigger piece of the Tier 0 action, and it still has some. But Facebook went off and created the Open Compute Project, and that took Facebook and eventually Microsoft out the picture. Amazon used to buy machines from Rackable Systems (eaten by SGI which was eventually eaten by HPE) back in the day, but started to do its own designs like Google; both rely on ODMs instead of OEMs to cut costs, and do so Facebook and Microsoft. The Chinese Tier 0s use a mix of ODM and OEM iron that is often somewhere halfway in-between.

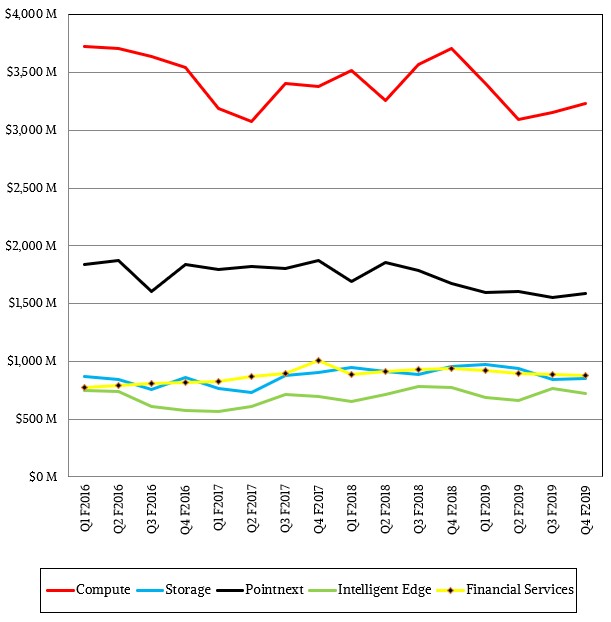

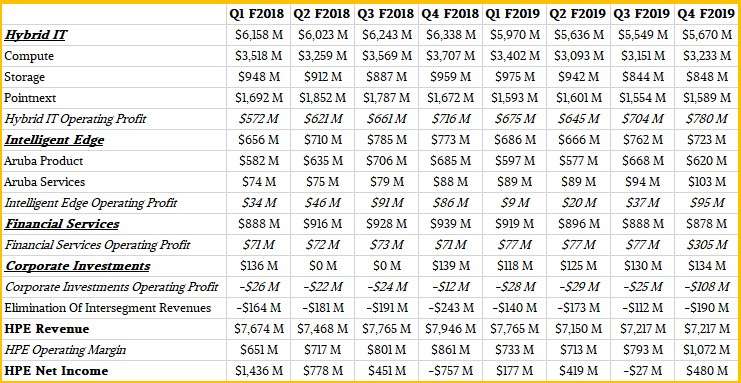

In the fourth quarter, HPE’s compute business, which includes all kinds of servers, stomached a 14.7 percent decline in revenues to $3.23 billion, and that includes currency effects and the Tier 1 winddown. Storage sales were off 13.1 percent to $848 million. Pointnext services, including GreenLake on premises infrastructure deals with cloudy pricing, accounted for $1.59 billion in sales, down 5.2 percent. All of this together is called Hybrid IT by HPE, had $5.67 billion in sales in fiscal Q4, down 11.8 percent.

Here is what the trends look like for the past three years that HPE has been talking about its revenues in the current product categories:

And here is the raw data for the past two years:

There are some bright spots in these numbers, which are not readily apparent. Composable cloud infrastructure, which means the HP Synergy line and related stuff, grew 21 percent in Q4, and attained $1 billion in sales in the fiscal year. The Apollo dense pack and sometimes water-cooled systems used by HPC centers and to run AI workloads also hit $1 billion in sales for all of fiscal 2019. Hyperconverged storage, which mixes virtual compute and virtual SANs, rose by 14 percent in Q4 and will be put into the storage category next quarter. (And therefore, the compute part of the business will take a hit abut Cray will be coming in and that will mitigate some of that decline.) Nimble Storage all-flash arrays rose by 2 percent in the quarter as well. GreenLake orders were up 72 percent year on year, and this business now has an annualized run rate of $462 million.

For the full fiscal year, HPC sales (which includes AI gear) grew 15 percent, and composable cloud sales rose by 47 percent with hyperconverged systems sales rose by 25 percent.

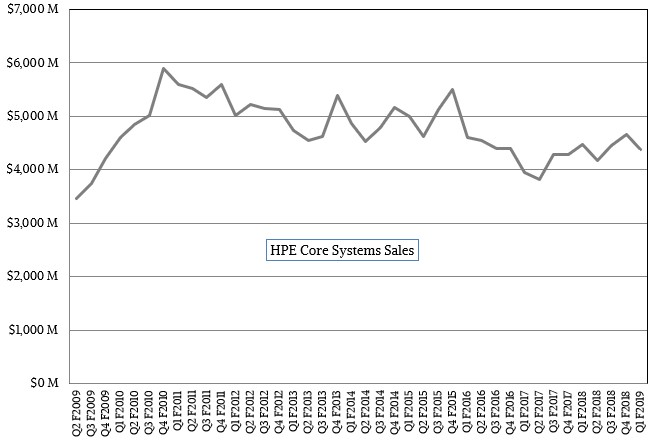

What we really care about – and what HPE has never talked about – is what its core systems business looks like. Despite all of the drama of divisions and businesses coming and going and being mixed and matched and moved around, sold off and bought, the real core systems business at HPE – including datacenter compute, storage, and switching – has remained remarkably constant. Take a gander at this:

We can’t prove this, but we suspect that almost all of this decline since 2009 is attributable to the exiting of business with the Tier 0 and Tier 1 service providers, using HPE’s lingo. As one business, such as the Itanium-based Superdome line, goes into decline, then another one rises, such as the Synergy composable systems and SimpliVity hyperconverged storage, rises. Considering all of the churn and chaos in the enterprise datacenter these days, having this relatively stable – but notably declining over the past decade – core systems business is an accomplishment.

There is nothing easy at all about any of this, and given the cards HPE has been dealt as well as pulled from the deck itself, it is hard to imagine playing it much differently. There are not infinite degrees of freedom for any company, after all. In fact, there are very serious limitations, and that HPE is now 80 years old is the truly amazing thing. This is a long, long way from making oscilloscopes for Walt Disney Company during the Great Depression.

Be the first to comment