Magneto-resistive random access memory (MRAM) is one of those technologies that is often talked about as having the potential to change the computer memory landscape. But in actuality, MRAM has been commercially available since 2006 and is already displacing static RAM (SRAM), dynamic RAM (DRAM), and flash NAND in number of applications inside and outside the datacenter.

Unlike DRAM, SRAM, and NAND, which rely on electronic charges to store bits, MRAM uses the electron spin to store information. It does this by using ferromagnetic plates to store the polarity of a magnetic element. Since electrons aren’t required, it takes much less energy to power these devices. In fact, compared to other non-volatile memory technologies like NAND, it is significantly more energy efficient.

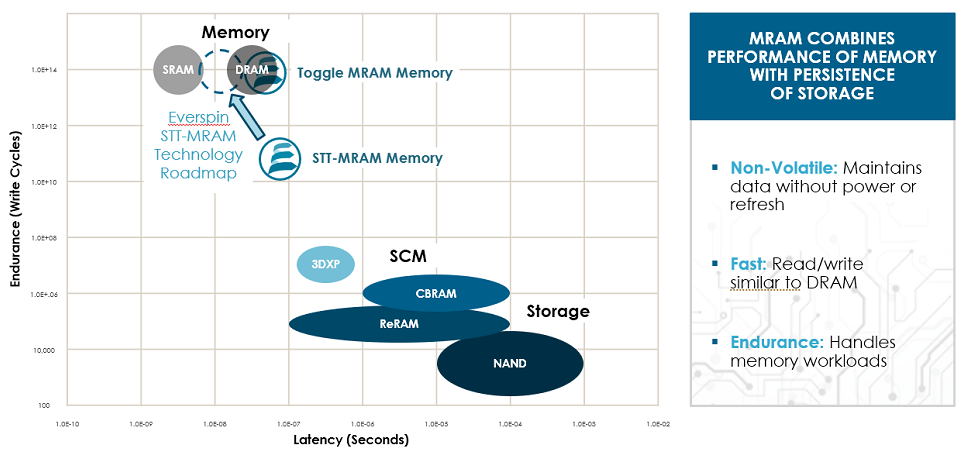

Just as important though, MRAM is among the most robust of the non-volatile memory technologies, with endurance similar to that of DRAM. If there is one limitation holding MRAM back, it is its relative sparsity, which directly translates to cost. Although MRAM can be manufactured at higher densities than of SRAM, it is not nearly as dense as either DRAM or NAND. Taken as a whole, though, MRAM’s attributes are often enviable, which has led some in the industry to suggest it can fulfill the role of a universal memory.

Leading the way in the MRAM market, at least for discrete devices, is Everspin Technologies, a company that spun out of Freescale Semiconductor in 2008. Everspin began shipping its first MRAM chips a year later and went public in October 2016. Today, the company has shipped over 120 million units and has more than a thousand customers, including some big names like Airbus, Honeywell, Cisco Systems, Dell EMC, IBM, and Inspur.

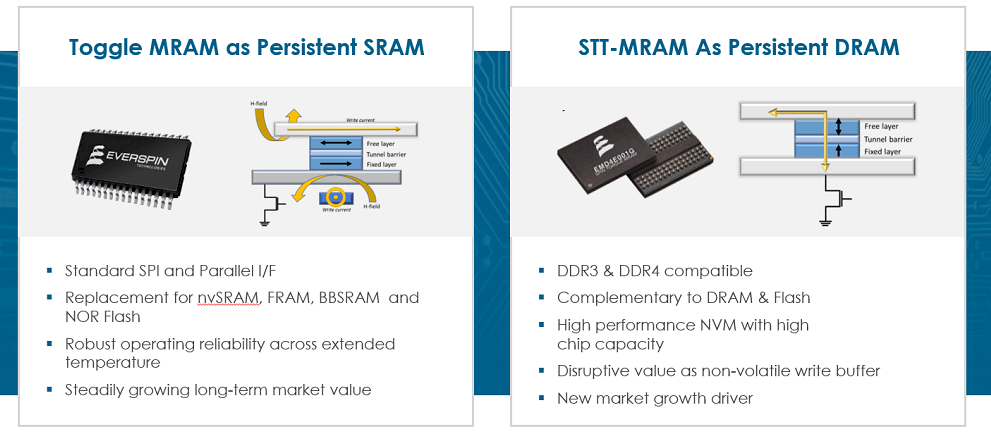

Everspin produces both Toggle MRAM and Spin-Transfer Torque MRAM (STT-MRAM), the two main flavors of the technology. The more scalable, denser STT-MRAM comes in capacities as high as 1 Gb and is targeted to applications that require a persistent DRAM component. As such, it can replace battery-backed DRAM.

In some situations, STT-MRAM can even replace flash or portions of it, especially where greater endurance is required. Troy Winslow, vice president of global sales at Everspin, who used to work at Intel in its flash memory group, says NAND is actually going in the wrong direction with regard to its wears characteristics.

“NAND has terrible endurance,” Winslow tells The Next Platform. “And you’re talking to a guy that spend eight years working with NAND and solid state drives,” adding that even the newer 3D XPoint technology developed by Intel and Micron Technology has less endurance than MRAM, not to mention it being slower.

The lower-capacity Toggle MRAM from Everspin is even more resilient than its STT-MRAM cousin and can last up to 20 years under a wide range of temperature regimes. Plus, it nearly matches SRAM in performance, with symmetrical read/write latencies of around 35 nanosceconds. That makes it a useful memory to replace non-volatile SRAM solutions in industrial applications in areas like military/aerospace, robotics, and IoT. Up until this week, Everspin’s Toggle MRAM chips topped out at 16 Mb, but this week the company introduced a 32 Mb offering, which should further expand its utility at the high end.

Everspin’s STT-MRAM can currently endure 10 billion cycles, which Winslow said is more than enough for any current datacenter application where it is being used. In the next generation, Everspin sees a path of not only increasing performance of STT-SRAM technology, but its endurance as well – up to the 100 billion cycle endurance of Toggle SRAM. That, he claimed, should give it essentially “unlimited endurance.”

Everspin’s more capacious STT-MRAM is not meant to replace all of DRAM – it doesn’t have the requisite density for that – but rather act as a non-volatile extender to main memory for things like buffering, journaling, and logging. It has been used as a transaction log device for FinTech applications in the datacenter. Specifically, STT-MRAM can serve as a high performance write buffer in front of a storage array of flash or disk drives that are recording financial transactions. Another datacenter application includes the replacement of battery-backed DRAM in flash controllers, which is used to buffer writes, as well as provide deduplication and compression, for solid state drives.

The rationale here is to remove the need for batteries or supercapacitors to back the DRAM in these circumstances, saving real estate on the board, as well as the cost of assembling the additional components. And since you don’t need to worry about the batteries or capacitors for backing up the power on DRAM, more MRAM capacity can be squeezed onto the PCB, which can increase application performance. The same goes for replacing battery-backed SRAM with Toggle MRAM. Beyond cost and real estate is just the unreliability of battery hardware, which usually lasts from three to five years, but not in a predictable manner. Avoiding that unpredictability is yet another reason why MRAM is edging out these persistent SRAM and DRAM solutions.

Winslow says when you factor in the price of the capacitors, batteries and surrounding PCB infrastructure, MRAM tends to be somewhat less expensive. He ran some scenarios using public pricing from a number of suppliers based on 4 Mb capacities and found that non-volatile SRAM solutions ran between $10.20 and $39.50, while the equivalent Toggle MRAM cost between $16.46 and $26.86. Standalone SRAM without power backup cost between $3.50 and $9.50 per 4 Mb.

MRAM can also be used to replace on-chip SRAM on devices like CPUs, FPGAs, and SoCs, but Everspin is not in the embedded MRAM business. The company leaves that segment to chipmakers like Intel and Samsung, which operate their own fabrication facilities.

“GlobalFoundries is our foundry partner and we are sharing in the cost of their MRAM R&D and tools and licensing our IP that benefits them from an embedded MRAM standpoint, and us from a discrete products standpoint,” Winslow told us, adding that without its own fabs, it just doesn’t make sense to be in the embedded MRAM market.

This is the right website for anybody who hopes to understand this topic.

You realize a whole lot its almost tough to argue with you (not that

I actually will need to…HaHa). You certainly put a brand

new spin on a subject which has been discussed for ages.

Great stuff, just excellent!