In the HPC cloud business, Oracle is a relative newcomer. As we reported in November 2018, the company jumped into the fray less than a year ago with HPC bare metal servers hooked together with a 100 Gb/sec RDMA network. Since then, the company has expanded the capability of the platform so that it’s now possible to rent a cloudy cluster with up to 20,000 cores.

As a result, Oracle is better positioned than ever to compete against on-premise infrastructure, something it tried to stake out early when it launched its HPC instance in 2018. Although it might seem counter-intuitive to challenge on-premise providers like Dell and Hewlett Packard Enterprise, inasmuch as in-house infrastructure tends to be less expensive than renting cloud hardware in the long term, the changing dynamics of the market is beginning to favor the utility model.

We recently caught up with Taylor Newill, HPC product manager for Oracle Cloud Infrastructure, to get a sense of how this strategy of challenging on-premise set-ups is playing out. One thing he brought up with us is that a lot of the Sun Microsystems employees that came on-board with the acquisition of the company in 2010 were eager to get back into the HPC business. “For the most part, those guys didn’t go anywhere,” he told us. “They were still building the hardware. They were just building it for our database appliance.”

With the introduction of the HPC instance for the Oracle Cloud, the company is once again developing servers with high performance computing in mind. Newill says the HPC instance is built on top of Sun Microsystems hardware, in this case, an X7 chassis. From a component perspective, it’s pretty straightforward: a dual-socket server powered by Intel Xeon SP-6154 Gold processors running at 3 GHz. Each server comes with 768 GB of main memory backed by 6.7 TB of local NVM-Express storage. The boxes are hooked together with a 100 Gb/sec Ethernet sporting RDMA over Converged Ethernet (RoCE), using ConnectX-5 network interface cards from Mellanox Technologies.

That’s pretty standard issue and is similar to what you might find in an enterprise HPC shop. And there are no hypervisors or other software intermediaries to tarnish the bare metal and eat away at performance. Newill admits Oracle is not offering subject matter expertise, as some cloud providers do. Nor is it pushing containers, although it has dabbled with Singularity. According to him, enterprise customers are just asking for the hardware.

Oracle’s related AI cloud offering uses the same bare metal concept, with an eight-way V100 system that performs on par with Nvidia’s DGX-1. In fact, Newill said Nvidia sends them customers who want to kick the tires on a densely configured V100 system if they’re in the market for a DGX box.

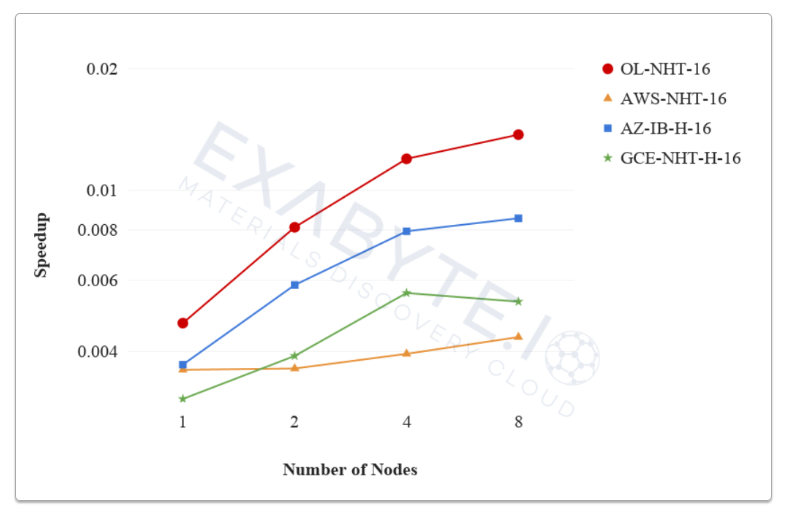

From a performance standpoint, Newill says their bare metal set-up is as fast or faster than on-premise clusters and is able to outrun the cloud competition on HPC codes. That’s backed up by a 2018 study by Exabyte.io that measured OCI, AWS and Azure instances on a number of HPC benchmarks, including High Performance Linpack, VASP, and GROMACS. The results showed that Oracle was consistently faster than other clouds, thanks mainly to their up-to-date componentry and their 100G RDMA network. The chart below illustrates the results for the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) package (OL=Oracle, AZ=Azure, GCE=Google Cloud, AWS=AWS).

Of course, that’s just a snapshot. Cloud infrastructure gets upgraded rather frequently, in fact, for more frequently than your average datacenter. And that, by itself, has become a draw for HPC users that have traditionally relied on in-house clusters. That attraction is becoming stronger since companies are tending to delay upgrades for their in-house systems. That’s happening for a number of reasons, one of which may be the easy availability of up-to-date hardware on public clouds, which makes for an interesting feedback loop.

Oracle’s main customers for HPC are large enterprises looking for big blocks of servers – companies like auto manufacturers and others big firms that need to run engineering or financial simulations. The way this often works is that Oracle salespeople have a relationship with the CIOs at these organizations as a result of their database business. For a fair number of these companies, HPC is a big line item. And if that’s the case, during a database license renewal, a salesperson is likely to bring up Oracle’s HPC cloud offering.

Occasionally, Oracle finds itself going head-to-head against AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud for HPC work. But these tend to be for smaller opportunities of a few hundred cores. Newill said they do pretty well in those circumstances as well because of their “aggressive pricing.” With the myriad of cloud offerings and discount models, it’s hard to do apples-to-apples pricing comparisons these days, but a report from Pilosa, did note “a two-node HPC2.36 cluster on Oracle Cloud is comparable in price to a three-node c5d.9xlarge on AWS, but has 5X the SSD space, significantly more processors, and triple the memory.” But for Oracle, it’s not a race to the bottom. It is looking to lure enterprise HPC customers with a level of price/performance that makes them attractive to CIOs.

In general, most users are looking to the cloud for one of two reasons: to get access to extra capacity as an adjunct to on-premise clusters or to pursue more of an OPEX budget model for their compute infrastructure. Both appear to be feeding into a growing demand for cloud-based HPC, which is supported by the latest numbers from Hyperion Research. They report that over 70 percent of HPC sites now run at least some of their jobs in public clouds, a figure that was just 13 percent in 2011. And according to Hyperion, over 10 percent of all HPC jobs are now in the cloud.

Newill says Oracle is seeing steady growth reflected in their HPC cloud business as well, but since Oracle doesn’t break out high performance usage from the rest of their cloud revenue, he couldn’t offer any of the particulars. He did, however, note that HPC was pretty much in line with their overall OCI business.

To support this growth, last year alone, Oracle built six new datacenters. This year it is building 12 more, with additional ones in the pipeline for 2020. It recently launched new centers in Tokyo and Seoul, with a Mumbai facility set to come online soon.

That kind of investment reflects the company’s direction, as was clearly outlined by CEO Larry Ellison at Oracle OpenWorld in October. Like many IT firms that used to sell software or hardware directly to end users, Oracle is shifting its database appliance business to a cloud model, with Oracle Cloud Infrastructure as the centerpiece. It goes without saying that they have no plans to start selling HPC clusters as Sun Microsystems did in the previous decade. For a big organization like Oracle, this kind of transition happens slowly, but the commitment appears to be there from Ellison on down. “The ship is turning, for sure,” said Newill.

Be the first to comment