Utility-style computing was not invented by Amazon Web Services, but you could make a credible argument that it was perfected by the computing arm of the retail giant. The IT industry has been trying to evolve towards what we now call cloud computing for quite some time, which was made possible by waves of hardware virtualization that started on mainframes, trickled down to Unix and proprietary systems almost two decades ago, and cascaded onto X86 machinery a decade ago. While cloud seems ordinary now, oddly enough it is still not the dominant architecture driving the IT industry.

At least not yet, anyway. If the hyperscalers like Google and cloud builders like AWS have taught us anything, it is to relentlessly measure, correlate, and analyze. To help understand what is going on in the IT sector as far as cloudy infrastructure goes, the box counters at IDC late last year started up a new tracker service that dices and slices sales of core infrastructure – servers, storage, and switches – into cloud and non-cloud piles and further chops the cloud portion into public and private parts.

The numbers confirm what many of us suspect intuitively, and that is that the move to cloud architectures is driving a lot of sales of shiny new iron. Cloud adds an orchestration and workflow layer on top of server virtualization, and increasingly is offering alternative technologies for managing bare metal machines and software containers as if they were clouds. Precisely how IDC is reckoning how bare metal goes into shops and then is converted into clouds rather than being presold as a cloud setup is not clear. (For decades IDC did similar estimates for operating systems on servers when a lot of machines were sold without an OS, causing some to be skeptical of its estimates.) We assume IDC has some insight, gained from all of the major server, storage, switch, operating system, and hypervisor makers as well as the big clouds and hyperscalers, to provide estimates that reflect reality within reasonable error bars. The server numbers certainly did for all those years, barring very aggressive prognostications for linear growth that never materialized during the dot-com bubble.

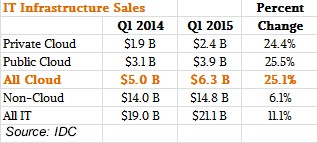

IDC has just released the figures for cloud infrastructure sales in the first quarter, and the results are consistent with the inaugural set of data that the market researcher put out in April for the fourth quarter of 2014. In both cases, public and private clouds together accounted for just under 30 percent of aggregate spending on servers, storage, and switching compared to the year ago periods. Sales of gear for building public clouds rose 25.5 percent, to $3.9 billion, in the first quarter of this year, and revenues from similar wares for building private clouds grew by 24.4 percent, to $2.4 billion.

If you take out the cloudy portions of the market and look at sales of servers, storage, and switches for siloed and monolithic workloads that, while they may be virtualized are not technically part of a cloud, the growth is much more anemic, according to IDC, even if it is more than twice as large as the cloud component. Server upgrade cycles are driving revenues both inside and outside of clouds at this point, says IDC, and in the case of the non-cloud portion, it is driving most of the growth. Without being specific – IDC has to make a living selling its data and can’t give it all away – the company said that non-cloud storage sales were down across datacenters worldwide in the first quarter, and Ethernet switch sales were up only 1 percent; nearly all of the 6.1 percent growth for non-cloud IT hardware sales in the datacenter came from servers.

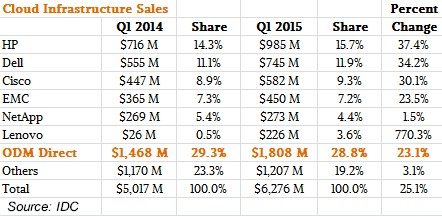

The top five vendors of cloudy infrastructure are the Who’s Who of the IT sector, with original design manufacturers comprising just under a third of sales across the three pillars of servers, storage, and switching. As a group, ODMs actually did not grow as fast as the market at large in the first quarter, rising only 23.1 percent – only is a funny word there, considering how anemic storage and switching growth is across the entire IT sector – to $1.81 billion. That gave ODMs a 29.3 percent share of the cloudy infrastructure pie. Hewlett-Packard, Dell, Cisco Systems, and EMC all grew their cloud sales faster than that, and we presume excepting HP and Dell, which make lots of iron for Microsoft for its public cloud, were concentrated mostly on the private cloud area.

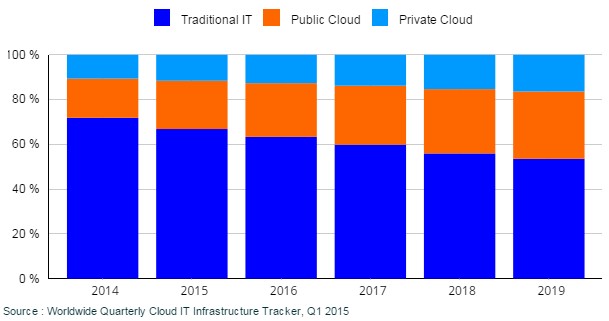

In addition to putting out numbers for the first quarter of this year, IDC also put out a forecast for cloud infrastructure spending that spans from 2014 through 2019. There are a few interesting elements in this forecast.

First, the prognosis for spending on servers, storage, and switching for cloud infrastructure is pretty good for this year, with 26.4 percent growth expected in 2015 and total sales of $33.4 billion and accounting for a third of overall IT sales for this equipment. That is a five point swing in share away from traditional IT and towards cloud within one year. Private cloud spending is only going to grow by 16.8 percent, to $11.7 billion, this year, but public cloud spending, will do almost double that growth at 32.2 percent this year and will hit $21.7 billion in aggregate sales for this core gear. Traditional, non-cloud IT will have flat sales and account for $67 billion in revenues.

As you can see from the chart above, it will take a long time before cloud becomes the dominant architecture in terms of revenues, and it looks like growth will be slowing according to the company’s forecasts. Over the first year period, the compound annual growth rate for cloud infrastructure spending is only 15.6 percent, but then again, that is a whole lot better than the 1.4 percent compound annual decline rate for spending on traditional server, storage, and switch gear during the 2014 through 2019 timeframe. At the end of the forecast period, public cloud spending on this gear will crest to $35.3 billion and private cloud spending will hit $19.2 billion, and together they will account for 46.5 percent of overall core infrastructure spending.

The amazing thing, perhaps, is the slow pace at which change comes to the datacenter. In a sense, the public cloud is a means for which conservative enterprises can initially adopt a disruptive style of technology such as cloud computing. From the forecast, and from our many conversations with end user companies and vendors alike, large enterprises and government and educational institutions are not looking for an either-or when it comes to cloud, public or private, but rather are positioning themselves with a hybrid model that keeps some applications and data in-house and others out on one or more public clouds.

To a certain extent, no matter what scale advantages public clouds offer, at some point a large enterprise may never move an application, just like cloud-native startups post 2008 or so will probably never, ever consider moving from a public cloud to their own datacenters. Unless, of course, they hit such a massive scale that the economics make sense. Such a case will almost certainly be the exception, not the rule.

Be the first to comment