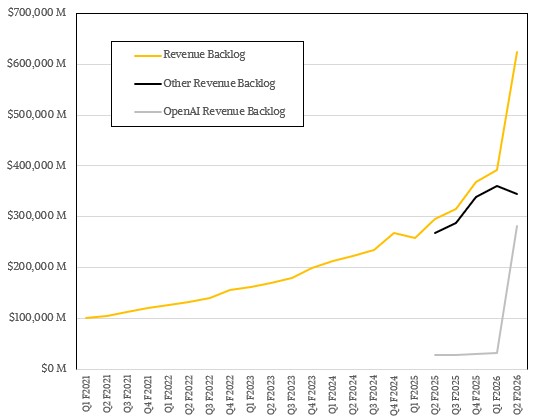

Everyone is jumpy about how much capital expenses Microsoft has on the books in 2025 and what it expects to spend on datacenters and their hardware in 2026. But the number that jumped out to us when reviewing Microsoft’s second quarter of fiscal 2026, which ended in December, was that OpenAI accounts for 45 percent of its $625 billion revenue backlog. That’s $281.3 billion, which will be spent over the next several years.

We can’t assume that this commitment from OpenAI to buy capacity on the Azure cloud to train its models and serve up tokens stretches all the way put to 2032, when the exclusive licensing of the source code to the GPT class of models created by OpenAI runs out. But, given how much money OpenAI is throwing around to Oracle, CoreWeave, Nvidia, AMD, and others – and how much it is raising from SoftBank and others – it is fair to assume that the current book of business with Microsoft is all that OpenAI plans to spend on Azure over the next seven years unless it suddenly needs a lot more GPU or XPU oomph.

What we do know is that OpenAI’s portion of the $625 billion in revenue backlog jumped by $250 billion following the signing of a new contract between the two companies last October. Amy Hood, Microsoft’s chief financial officer, said on a call with Wall Street analysts that the non-OpenAI part of the Microsoft revenue backlog grew by 28 percent. When you do some multiplication, you can get the non-OpenAI portion of the backlog from a year ago, and one subtraction gets you the OpenAI piece. Assuming something akin to linear growth for OpenAI in the months between, you get a backlog picture that looks like this:

Now, OpenAI has been part of the Microsoft revenue backlog since Microsoft invested $13 billion in OpenAI over several years before and during the GenAI explosion. A substantial portion of this money, man plus dog believes, was roundtripped back to Microsoft as fees for using Azure capacity to train GPT models – exactly when and where, only Microsoft and OpenAI know. If we have such data, we could extend the chart above back in time for a fuller picture.

But, alas, we can only work with the numbers we are given or can guesstimate with some confidence.

The issue for Microsoft is that Wall Street is touchy about the growth of its Azure infrastructure cloud business, and as the numbers show, Big Bill is a lot more dependent on OpenAI than OpenAI will be on Big Bill. Which reminds us of the old saying: “If I owe you $250, that is my problem. But if I owe you $250 billion, that is your problem.”

Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s chief executive officer, is nonetheless cheery about the GenAI future it has in store for the billions of users of the Windows platform and the company’s various personal and corporate applications.

“We are in the beginning phases of AI diffusion and its broad GDP impact,” Nadella explained on the call with Wall Street. “Our TAM will grow substantially across every layer of the tech stack as this diffusion accelerates and spreads. In fact, even in this early inning, we have built an AI business that is larger than some of our biggest franchises that took decades to build.”

As a person who has turned off all the copilot functions I can find on my Windows desktop, and knowing I am not alone, I find this hard to believe. OpenAI must represent the largest part of Microsoft’s actual AI business, which means the other parts are small. And if Microsoft raises software prices to cover the cost of AI functions, and then breaks those out separately, I did not really chose its AI even if my money is paying for it.

And for the record: I have no problem with Google Gemini enhancing my searches, and I have a modest subscription to Anthropic’s Claude that I use for more advanced searches and sometimes to check my math when I am doing something complex. Even Albert Einstein had Mileva Marić (his friend from Zurich Polytechnic and eventually his wife) and Marcel Grossman (also a classmate) to check his math on relativity. My wife, Nicole, started out long before me using GPT, and I chose Claude as the model to play with mostly to be contrarian and expansive. Both Nicole and I do our own analysis and writing, and I still build my spreadsheets the old fashioned way with my fingers.

The overall Microsoft Cloud business only grew at 39 percent in the quarter – a little lower than was expected – and even though Hood told Wall Street that Microsoft was using a lot of its GPU capacity for other things – presumably to train its own models, to run inference for copilots and other applications like Microsoft Foundry, and to get capacity to OpenAI – rather than putting them up for rent on Azure and that if it had not used so many GPUs internally it could have boosted Azure revenue growth well above 40 percent, all that investors heard was Microsoft didn’t do that.

They also heard that Microsoft had spent $37.5 billion on capital expenses in the quarter to boot. Depending on who you ask, Wall Street is expecting for Microsoft to spend $100 billion to $125 billion on capex in F2026, up significantly from the $88.2 billion it spent on capex in fiscal 2025. And they remembered that Microsoft has said that it wants to double its datacenter capacity by the end of fiscal 2027.

Hence, Microsoft stock lost some air. The good news – and it is not clear that people have done the math – is that Microsoft’s datacenter spending will be at least partially covered by the revenue coming in from OpenAI. And as other enterprises embrace GenAI, Microsoft will be able to recoup its investments in a matter of years. In fact, Hood said that the GPUs it is installing now on Azure for external use have already had allocations out to the end of their useful life. (This should be six years, since that is the stated useful life of Azure servers.)

With that, let’s drill down into the Microsoft numbers for Q2 F2026.

In the December quarter, Microsoft’s product revenues rose by 1.4 percent to $16.45 billion, and both its PC and server businesses have been adversely affected by high prices and shortages for main memory and flash storage. Services and Other revenues came to $64.82 billion, up 21.4 percent. Add it up, and you get $81.27 billion in sales, up 16.7 percent, and an operating income of $38.28 billion, up 25.3 percent. Net income was $38.46 billion, aided by a $7.6 billion gain from its 27 percent stake in OpenAI. (In Q1 F2026, OpenAI’s books put a $3.1 billion loss on Microsoft’s books.) The remaining $2.4 billion in Other income came from interest and other stuff.

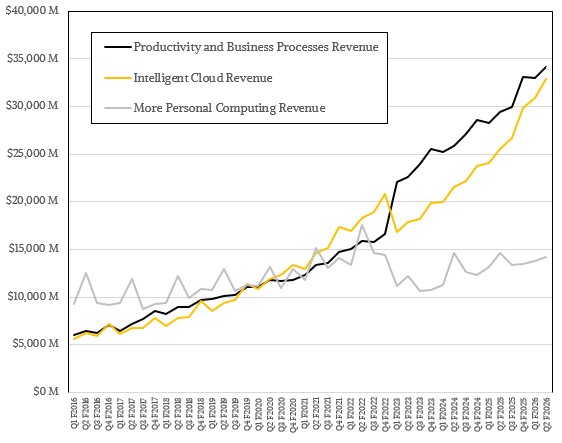

The Intelligent Cloud group at Microsoft – which includes the Windows Server platform as well as the Azure cloud – had $32.91 billion in sales, up 28.8 percent, and operating income rose by 27.8 percent to $13.78 billion.

As you recall, a few years back Microsoft pulled revenues it had been booking in its datacenter and PC platform businesses and put them into its application business. This had a dramatic effect on the curves, and we cast it back as far as we could. The thing you will notice is that the Intelligent Cloud business took a smaller hit than the PC business from this reclassification, and has largely recovered. The PC business has been growing, but nothing too extra.

Microsoft doesn’t supply revenue and operating income figures for the Azure cloud directly, but we have diced and sliced its financials and figured out a way that we think accurately reflects the revenue stream from the infrastructure and platform services that make up the base Azure cloud.

By our model, the Azure cloud proper brought in $21.95 billion in sales and represented precisely two-thirds of the Intelligent Cloud business in Q2 F2026. Further, our model says that the Azure cloud had an operating income of $9.72 billion, up 44.8 percent and representing 44.3 percent of Azure revenues. What we do not know is how much of the sales at Azure – and interestingly, how much of the growth in Azure revenues – has been due to OpenAI’s tremendous cloud bill.

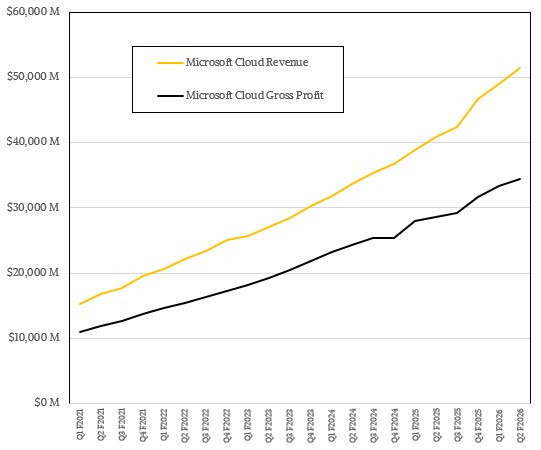

The overall Microsoft Cloud business – which means the Azure infrastructure plus any cloud subscription for any of the company’s software as opposed to perpetual licenses and tech support – broke through $50 billion for the fist time in the company’s history. In as much as cloud is just a delivery and pricing model, it is interesting that the Microsoft Cloud had $51.51 billion in sales, up 26.2 percent, with gross profits of $34.51 billion, up 20.8 percent. (Microsoft does not provide operating profits for this segment of its financials.)

What we like to calculate for all the major IT players is what their “real” systems business is inside the datacenters of the world so we can compare across OEMs and clouds and component suppliers into these companies.

When you add up all that Windows Server systems software (extracting out databases, development tools, and other stuff that is not base systems software like operating systems and hypervisors and container controllers. and add in all that Azure cloud capacity that is rented for compute, storage, and networking, we think Microsoft’s “real” systems business brought in $22.58 billion in revenues, up 31.9 percent year on year, and had an operating income of $9.52 billion, up 30.9 percent. Admittedly, there is a lot of good guesswork to extract that stuff out. It would be best if Microsoft just told us.

By the way, the blip down sequentially for this real systems business is more about how databases and development tools are growing faster than they were and contributing more to the revenue and profit stream at Microsoft. So don’t get freaked out about that.

Be the first to comment