Here’s a riddle for you: What’s the difference between an economic bubble and an economic transformation? I don’t know, but if either pops, a bunch of economists are gonna lose their jobs. And if the GenAI bubble keeps on embiggening or the GenAI transformation keeps on expandening, a whole lot of people will likely end up on universal basic income, whatever the hell that actually means.

Everybody wants to know if the GenAI boom, which has gone from chemical to nuclear, is a bubble or not. The only way to be sure is to live through the next five, six, or seven years and find out. Inasmuch as economic expansions tend to blow bubbles – periods of excessively optimistic investment in a technology driven by enthusiasm, fear of missing out, greed, and other market forces that arise out of the force field comprised by the confluence of human nature, technology, and money – this is a normal concern. And the fact remains that it is very hard to tell the differences between a bubble and an expansion/transformation from the inside.

But the situation is even more complicated because there are actually two AI bubbles to consider. First, there is an inner one that is the bubble in spending for AI infrastructure, the datacenters that wrap around it, and the electricity that powers it and the water that often cools it. And then second, there is the outer bubble of market valuation, which is the combination of the AI businesses of public companies and the aggregate valuation of maybe 15,000 or 20,000 AI startups that have been funded and are all trying to do their part to swell that outer bubble while participating in that inner bubble. These bubbles touch at the wand and are connected, but can grow and even pop independently. But if one pops, the odds increase that the other will. Sentiment in one bubble bleeds over into the other.

Double, Double Toil And Trouble

Nvidia co-founder and chief executive officer Jensen Huang was having none of this talk about an AI bubble when he spoke on a conference call with Wall Street analysts going over the financial results for the company’s third quarter of fiscal 2026.

“There’s been a lot of talk about an AI bubble. From our vantage point, we see something very different. As a reminder, Nvidia is unlike any other accelerator. We excel at every phase of AI from pre-training and post-training to inference. And with our two decade investment in CUDA-X acceleration libraries, we are also exceptional at science and engineering simulations, computer graphics, structured data processing to classical machine learning.”

One of the things we all have to do as we try to make sense of where Nvidia is at and where it might grow is speak very precisely. Back in late August, as we previously reported, Huang said that trillions of dollars in spending for AI was in the works as IT organizations the world over added new functions and transformed others. Huang put some numbers on it thus:

“We are at the beginning of an industrial revolution that will transform every industry. We see $3 trillion to $4 trillion in AI infrastructure spend in the – by the end of the decade.”

We took that line literally and set about building a model. Of every $50 billion that is spent to build a 1 gigawatt AI factory, Nvidia gets $35 billion of that, which works out to 70 percent share of the pie. So that works out to somewhere between $2.1 trillion and $2.8 trillion going to Nvidia. At current profitability levels, that would be net income ranging from $1.2 trillion to $1.6 trillion. Our model projected Nvidia would have maybe $1.66 trillion in sales in fiscal 2026 through fiscal 2030, inclusive and assuming that is what Huang meant when he said “by the end of the decade,” with diminishing profits due to competition and higher costs of putting stuff into the field as chips and packaging get more costly. Call it a mere $750 billion in aggregate profits over those years.

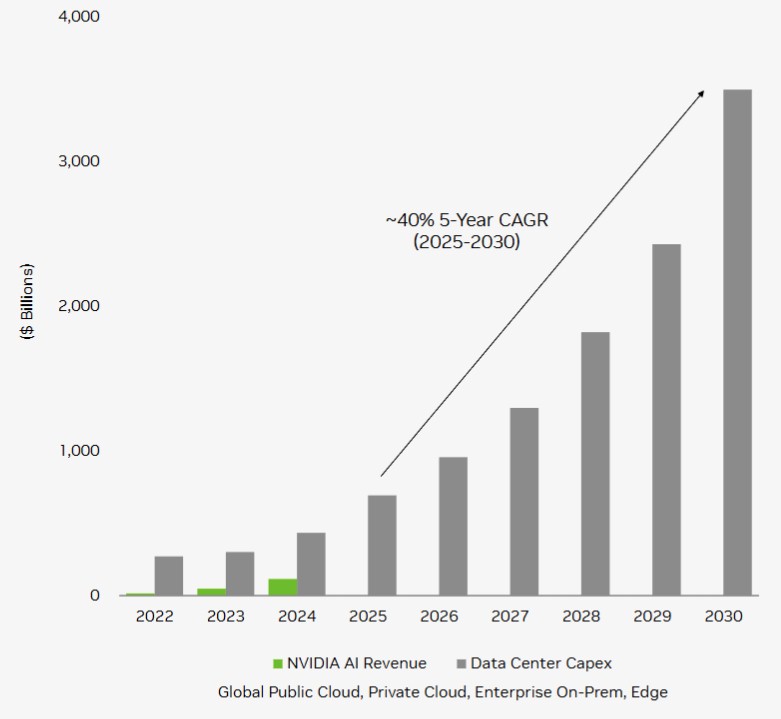

This sounded like a lot of money. As it turns out, Nvidia’s AI forecast was a lot broader and larger, as we see from an investor presentation that was just put out by the company:

We got out the pixel counter and reverse engineered the data for this datacenter capex spending chart presented by Nvidia, which includes AI spending by the cloud builders, by cloud infrastructure outposted to enterprises, by enterprises buying their own AI gear, and by something Nvidia simply called “Edge,” which we presume is not the lead guitarist of U2 and which is all of the edge stuff that will be installed. Nvidia wants to be at the AI edge as much as it wants to be in the AI datacenter, and this could ultimately be a large part of the market.

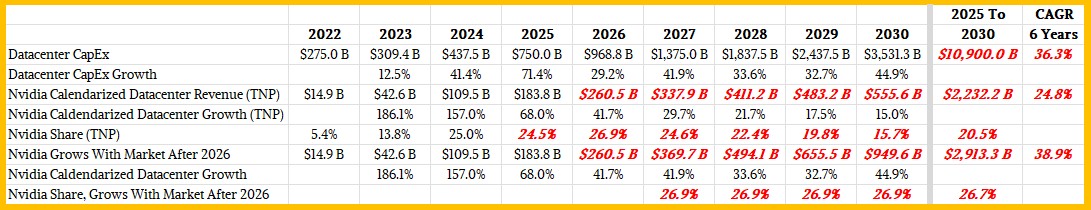

Anyway, we reverse engineered the datacenter capex spending shown in the Nvidia presentation. And then we updated our Nvidia model to reflect the $500 billion or so in business for “Blackwell” and “Rubin” GPU systems that the company said it would sell between now and the end of calendar 2026 when Huang gave his keynote back at GTC DC 2025 in late October. We think that there will be immense competition in the AI XPU space in the years ahead and that Nvidia’s growth will slow even as datacenter capex spending for AI skyrockets. We also think this is a very optimistic overall datacenter capex spending forecast, and frankly, we though a total addressable market between now and the end of the decade at $3 trillion to $4 trillion was a little high. This new chart from Nvidia above show $10.9 trillion in spending, which is 3.2X to 2.7X higher than what we thought was high.

Go figure.

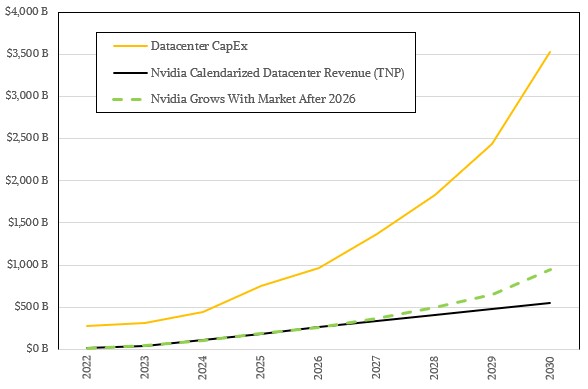

Taking this at face value and marrying it to our estimates for calendarized Nvidia datacenter revenues with a projection for slowing growth gives this forecast from us:

Nvidia’s revenues have been growing faster than the datacenter capex spending on AI for the past several years, and the dashed green line shows what will happen if Nvidia grows as fast as the aggregate global AI capex budget between 2027 and 2030, inclusive.

If Nvidia can do that, then it will hold around 27 percent of the total bill of materials for AI datacenter capex spending. If not, as our model shows, then Nvidia’s share will drop. We happen to think that overall datacenter AI capex will not be as large and Nvidia will maintain its share. And remember: Nvidia sells chips, system boards, racks, switches, and cables, but ODMs and OEMs make the actual systems from these components and it is this level of number that is counted in the overall datacenter AI capex shown. (Granted, Nvidia gets a lot of this capex as revenue by virtue of supplying a lot of the parts.)

Fire Burn And Cauldron Bubble

This capex curve above shows Nvidia will not have dominant market share, that the cloud builders, and model builders, and hyperscalers will start deploying their own alternatives, or it shows that the overall capex spending forecasts numbers are tremendously inflated given the enormous sums required to be spent between 2025 and 2030. The gross domestic product of the United States as a whole is only expected to be $30.5 trillion, just so you have a benchmark.

Anyway, here is the table for the data in the chart above:

This Nvidia datacenter capex spending forecast at $3.53 trillion is considerably larger than the more than the $1 trillion or so forecast that AMD put out for AI datacenter infrastructure silicon spending last week. AMD is expecting a compound annual growth rate above 40 percent between 2025 and 2023, and Nvidia is talking about “around 40 percent.” So they agree, more or less, on something.

Because our brain loves irony, as we were writing this story, all I could hear was Don Ho singing Tiny Bubbles, which was one of my father’s favorite songs. (He loved Hawaiian steel guitar, and played it often.) These bubbles are not very tiny at all, but the most certainly are in the sand. . . .

Here is the thing: Just because a bubble forms doesn’t mean the world is not changed by the railroads or Internet technologies or GenAI even if the bubble bursts. One might argue that the Dutch tulip bulb bubble of 1636 and 1637 was just plain stupid, and the overcapacity in the fiber networks concurrent with the Dot Com boom was a kind of irrational exuberance that didn’t make a lot of sense. I don’t think anyone can make a credible argument that GenAI and more traditional machine learning, running on GPU-accelerated systems, is not a key part of the future systems that will run the world. It may be harder to make money from it than it looks in the charts above, as hard as this might be to believe right now.

Then The Charm Is Firm And Good

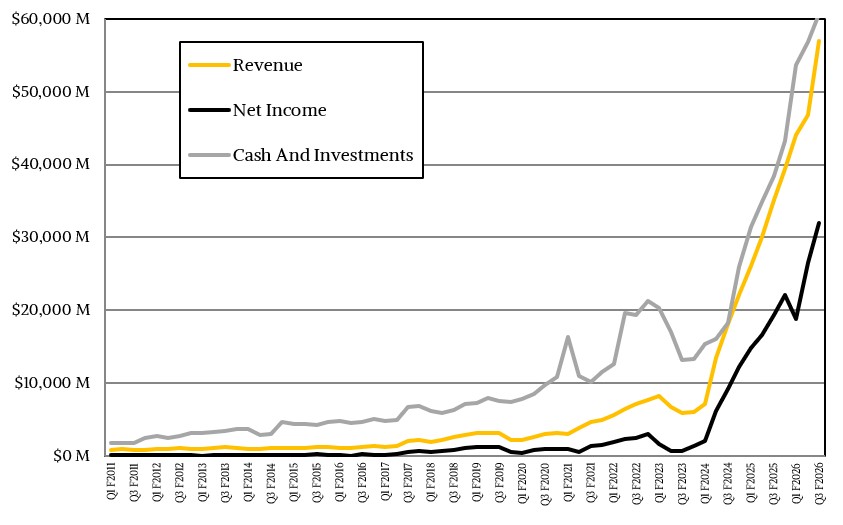

Back here in the first present, where we talk about actual numbers, Nvidia turned in what can only be called a spectacular quarter, and Wall Street was initially happen and then did some pondering and profit taking, making Huang a little punchy about Wall Street apparently.

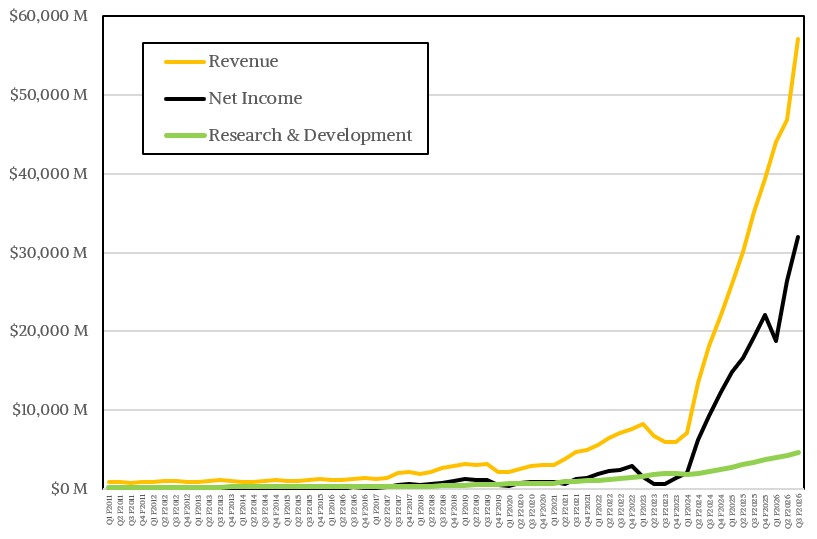

In the quarter ended in October, Nvidia’s overall revenues rose by 62.5 percent to just a tad over $57 billion, and operating income was up by an even larger 64.7 percent to just a tad over $36 billion. Net income was $31.91 billion, up 65.3 percent and working out to an incredible 56 percent of revenues. Nvidia ended the quarter with $60.61 billion in cash and equivalents, which is one reason why Nvidia can be generous with investing in model building and cloud building customers.

It is also why Nvidia can spend a lot of money on research and development, although R&D as a share of revenues is tiny compared to what it used to be before the GenAI boom rapidly accelerated Nvidia’s revenues but not so much its costs:

The $4.71 billion in R&D spending during fiscal Q3 was the highest ever spent by the company, but it only represents 8.3 percent of revenues. In the old days before the GenAI boom, it was not uncommon for Nvidia to expend a quarter to a third of its revenues on R&D. This GPU thing is a serious profit engine.

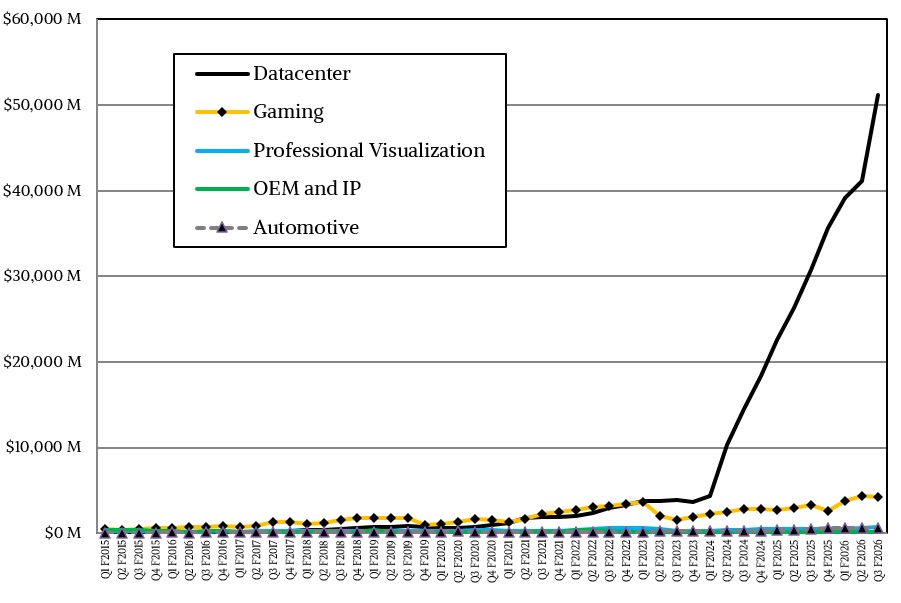

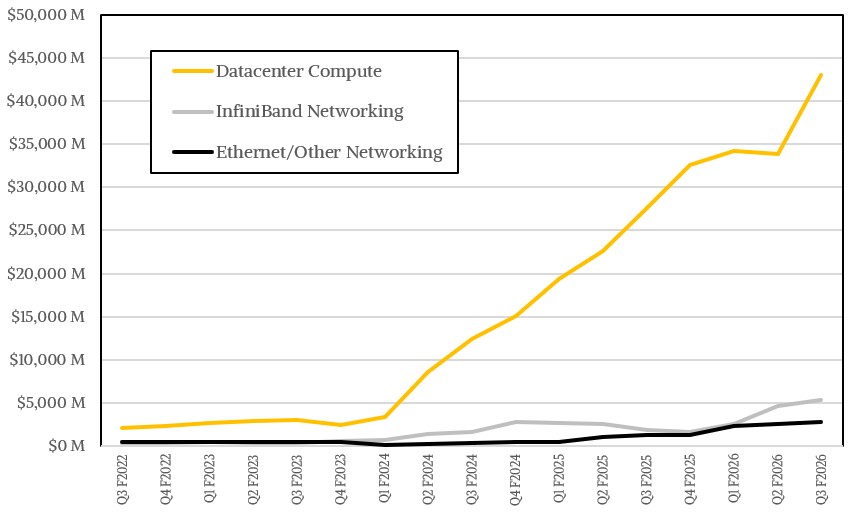

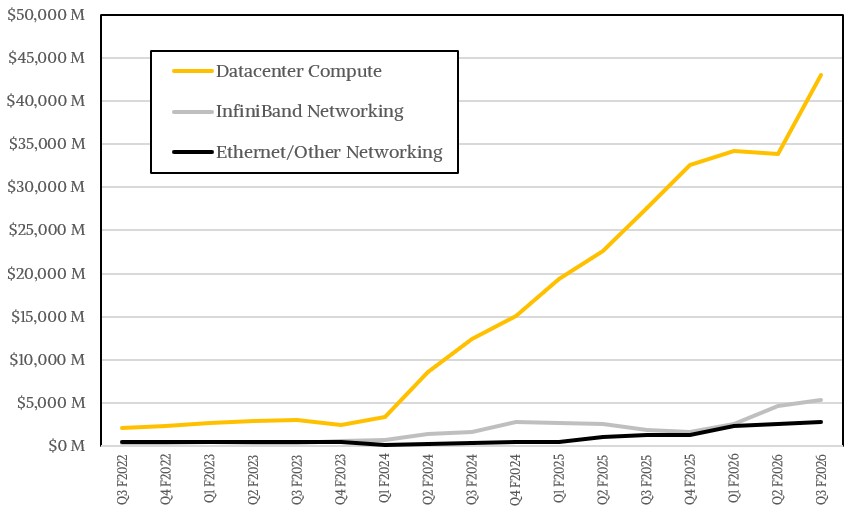

Nvidia’s Datacenter group, which is by far the dominant part of the company now, had $51.22 billion in sales, up 66.4 percent year on year and up an amazing 24.6 percent sequentially. Truly amazing. Nvidia said that everything in the datacenter – compute, InfiniBand networking, Ethernet networking, and NVSwitch networking – was growing at double digits, but as far as we can tell, it was growing at that pace sequentially and much higher on a year-on-year basis.

In our model, Nvidia had $43.03 billion in datacenter compute revenues, up 55.7 percent and up 27.1 percent sequentially. This is astounding. But networking is growing even faster as companies build out coherency across racks. We think that InfiniBand revenues were up by a factor of 2.9X to $5.51 billion, and Ethernet and NVSwitch revenues together comprised $3.07 billion in sales, up 2.2X year on year and up 10 percent sequentially. (We have yet to recast the model to separate out Ethernet from NVSwitch, but we are working on it.) Remember: these revenues are not just for ASICs and switches, but also for transceivers and cables, which comprise a big part of the networking bill in the modern datacenter.

On the call with Wall Street analysts, Colette Kress, Nvidia’s chief financial officer, said that the company sold about $2 billion in “Hopper” H100 or H200 GPUs, and we think the vast majority of that was for H200s. That leaves the remaining $40.93 billion for “Blackwell” B200 and “Blackwell Ultra” B300 GPUs, and Kress added that about two-thirds of the Blackwell sales were for B300s. (Hey: Thanks for the actual data.) That’s about $13.51 billion in B200 stuff and about $27.43 billion in B300 stuff if you do the math, and that is also 19.5X more overall Blackwell stuff compared to the year ago period as far as we can tell.

Nvidia did not give a split on sales based on AI inference versus AI training versus traditional HPC for its GPU system components, but we think (based on hunches and past data) that on a trailing twelve month basis, AI inference represented around $99 billion in revenues, AI training around $86.5 billion, and HPC around $6.7 billion.

One last thing to bring it all back home. Even if this is a bubble and if it is going to burst when and if financing dries up – Nvidia is going to sell a whole lot of hardware and systems software compared to its historical datacenter business.

Nvidia can grow slowly and still amass enormous revenues and profits, as our model shows.

For instance, the company could capture more of that datacenter capex spending forecast above by moving more aggressively into high-end storage (there are acquisitions that could be made) and into datacenter components (as Supermicro, Dell, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Lenovo, and others have done). There is a large amount of TAM that Nvidia does not address, as its own chart clearly shows. And if the bubble bursts, or growth simply slows, expect Nvidia to do more vertical integration to keep its own business growing and to compete more aggressively with the competition inside the hyperscalers, cloud builders, and model builders.