For the past two years now, we have been picking apart the semi-annual rankings of supercomputers known as the Top500 is a different way, focusing on the new machines that come into each list in either June or November. This, we thinks, gives us a sense of what people are doing, right now, when it comes to buying supercomputers rather than only looking at the five hundred machines that happened to submit benchmark results on their systems using the High Performance LINPACK (HPL) benchmark test.

This was the weakest list since June 2024, when we first started analyzing the Top500 in this manner, in terms of new machines and aggregate performance in terms of cores and Rpeak flops. It wasn’t awful, mind you. It’s just that there are not a lot of new big machines on the list, just like there wasn’t back in June 2024. This is part of the upgrade cycle and the funding cycle, which used to be more tightly coupled before GenAI came along and became the cycle, with traditional HPC no longer setting the pace.

We would argue that traditional HPC does more real work and is, even with nuclear weapon stewardship in the United States and Europe, less destructive than AI might turn out to be in the long run.

Since the June 2025 list was locked down, 45 new machines have been fired up, run the HPL benchmark, and had their results submitted to the Top500 organization. That doesn’t mean only 45 relatively large supercomputers have been installed worldwide in the past five months. There are plenty of machines that don’t submit HPL test results – notably, the clusters running in the national labs in China and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois all boycott the Top500 – even if they do run the test as part of their system shakedown. The Top500 is an important indicator and dataset, but it by no means encapsulates the entire HPC market.

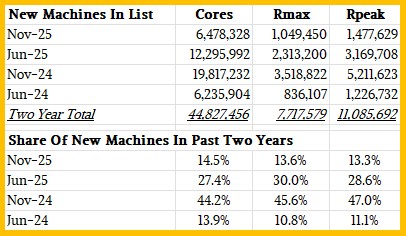

Those 45 new machines added to the Top500 list had 6.48 million cores – that is counting both streaming multiprocessors on GPUs and cores in CPUs – and a peak aggregate performance of 1.48 exaflops. In June 2025, the list had roughly twice as much capacity added and in November 2024 nearly three times as much capacity was added thanks to the changing of the HPC system guard among the national labs in the United States. We have written about all of these machines before, and we are not going to rattle off feeds and speeds for these systems again. You can read the list yourself to see that.

What is less obvious is the fact that the newest machine on the list, the CHIE-4 system installed by SoftBank, is the largest new system and it only ranks at number 17 on the list. The Shaheen-III GPU partition at KAUST, one of only five Nvidia CPU-GPU superchip systems added this time around, is number 18 on the list.

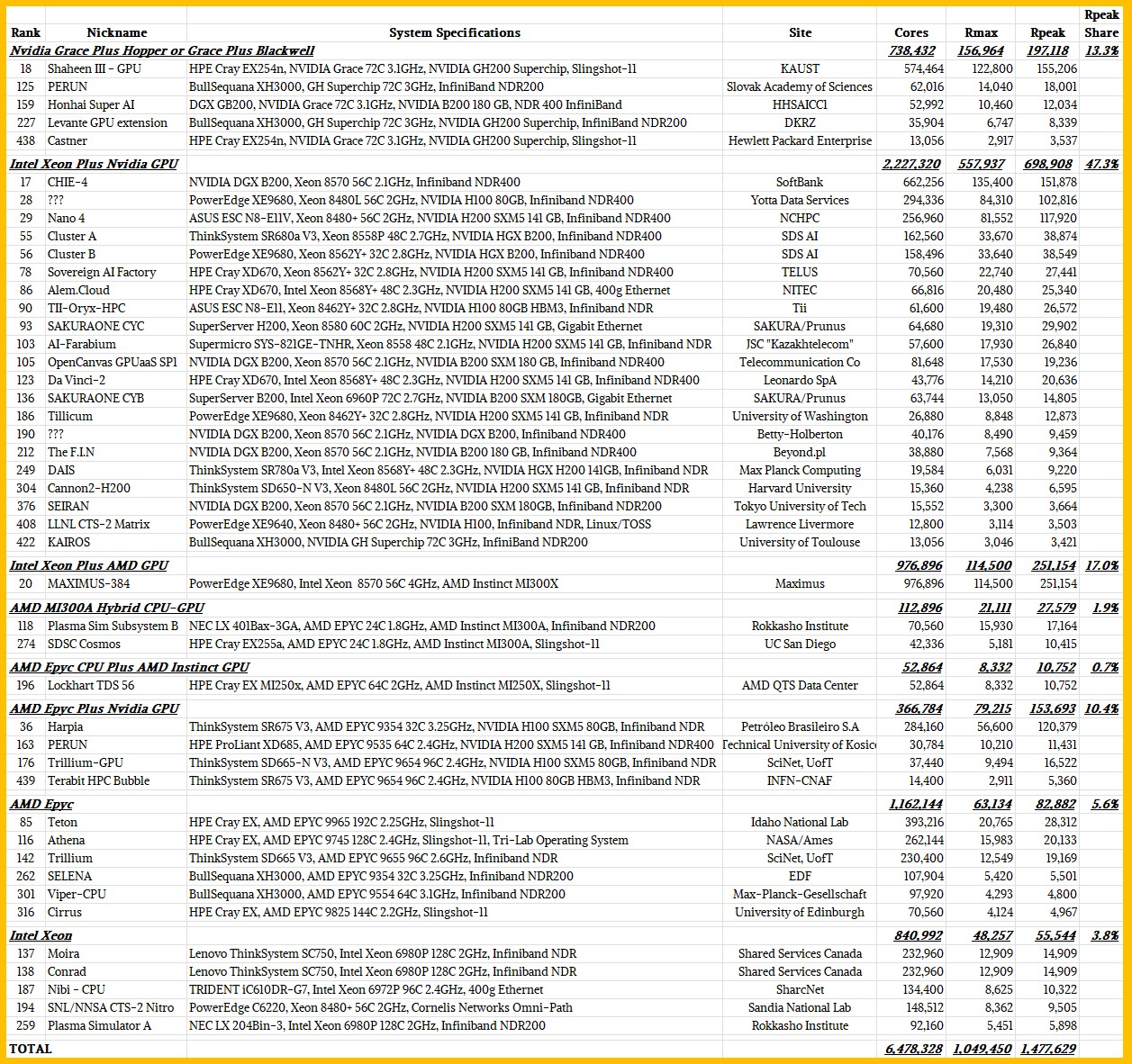

Here are all of the new machines added to the November 2025 Top500 list, segmented by their processor architectures:

Those five supercomputers based on Nvidia’s “Grace” CG100 Arm server CPUs paired to either its “Hopper” H200 or “Blackwell” B200 GPU accelerators accounted to 197.1 petaflops of peak aggregate floating point performance at 64-bit precision, which was 13.3 percent of the new capacity at that FP64 precision added between July and November this year.

What we find interesting is that there are 21 machines that have Intel Xeon CPUs and paired with either H100, H200, or B200 GPU accelerators. Together, these 21 machines accounted for an aggregate of 698.9 petaflops of aggregate FP64 performance, which was 47.3 percent of the 1.48 exaflops of total FP64 performance added this time around.

One of the interesting new machines on the list was built for US federal government service provider Maximus by Dell using its PowerEdge servers and equipped with Intel “Emerald Rapids” Xeon 5 processors paired with AMD Instinct MI300X GPU accelerators. This machine had an Rpeak of 251.2 petaflops and represented 17 percent of the new capacity installed on the November Top500 rankings.

There were two machines, as you can see in the table above, that are based on the AMD MI300A hybrid accelerators that were famously deployed in the “El Capitan” supercomputer at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. This machine is still ranked number one on the Top500, with an Rpeak of 2.821 exaflops and an Rmax throughout on the HPL test of 1.809 exaflops. A few new machines on the November list mix AMD Epyc CPUs and Nvidia Hopper GPUs, and there are six new machines that are just using AMD Epyc CPUs as compute engines and another five new machines that are using Intel Xeon CPUs solely. The CPU-only machines account for only 9.4 percent of the aggregate Rpeak capacity even though they are 24.4 percent of the new systems added in the November list.

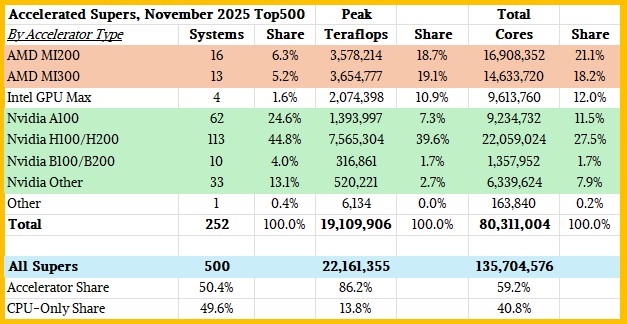

We are always intrigued by the number of machines that are accelerated, and in the November 2025 Top500, it broke through more than half of the base of five hundred machines:

All told, the Top500 this time around had 22.16 exaflops of aggregate performance, and accelerated machines accounted for 86.2 percent of that aggregate performance at 19.11 exaflops. CPU-only systems on the list only accounted for 13.8 percent of the aggregate FP64 oomph.

Of the machines that are accelerated, AMD GPUs accounted for 37.8 percent of the performance pie, with Nvidia GPUs getting 51.3 percent, Intel GPUs getting 10.9 percent, and other accelerators getting a fraction of a percent. This share split between AMD and Nvidia in the HPC sector might be a leading indicator for the market at large, and very closely matches the Nvidia revenue share we calculated in our AMD forecast story from last week. (The Top500 was not released until after we wrote that AMD story, just to be clear.)

While next year is going to be boom time for GenAI training and inference centers, it is not clear how traditional HPC centers will be funded, even with the nine new machines the US Department of Energy is funding over the next few years at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Argonne National Laboratory, and Los Alamos National Laboratory. We don’t have much in the way of details about those machines, which will use Nvidia and AMD compute engines. We hope to find out more this week at SC25.

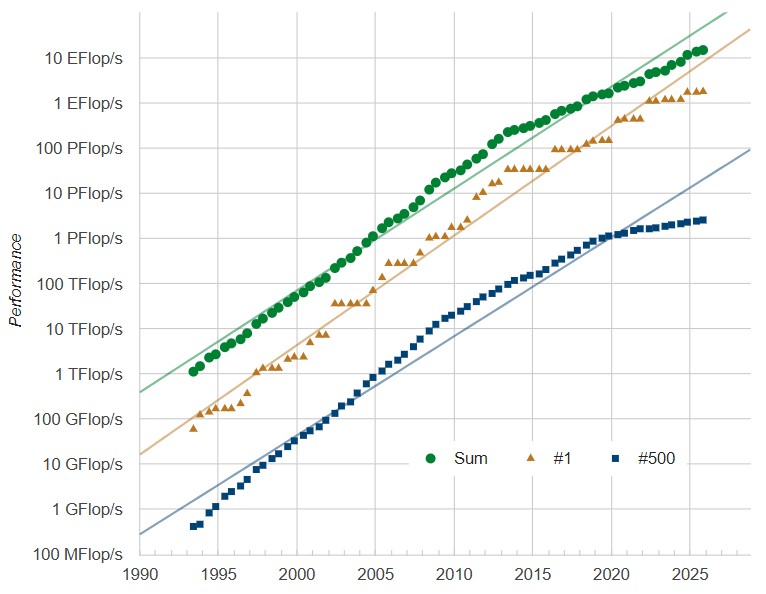

No matter what, it would take an enormous investment to get supercomputing back on the Moore’s Law curve, which the industry slipped off of many years ago:

As you can see from the chart above, which comes from the Top500 dataset itself, the biggest machine in the world should have maybe 8 exaflops of aggregate peak FP64 compute and the installed base of compute should be maybe twice as large as it is. You should need more than 10 petaflops to even get a machine on the list at all, based on trends. It is ironic that as HPC capacity increases are bending down, AI training systems have been bending up and have many orders of magnitude more computing, and lower precision that drives AI performance further than might be otherwise possible. Mixed precision solvers can fill in a lot of that gap, but it is not clear at all how many real-world HPC applications are making use of them.

Comments are closed.

While it’s already been mentioned that the Top500 is not a measure of available compute power for science and engineering, it does make an interesting spectator sport as well as stress test for newly installed hardware.

A better glimpse of the science might be provided by the Gorden Bell prizes as well as the impact of published research that acknowledges use of a particular supercomputer. At the same time, since once a metric becomes a goal it ceases to be a metric, the Top500 is relatively harmless in comparison to the possibilities.

Speaking of metrics, I wish it were more widely reported the percentage of time used by leadership-class capability jobs versus small jobs versus idle time. Efficient use of computing resources are important; however, there is no optimal balance between capability jobs and everything else without knowing who needs what and why. Even so, I think it would be an interesting statistic to compare.

Yup. Agreed. Some data is always better than no data. We just want to it be representative of something, as it used to be.

I hear that the idle time metric is surprisingly high on some of the AI systems out there, but is probably very low on most of the other HPC systems. (Unless you count maintenance time) What constitutes a capability job probably differs site to site. Maybe need a uniform definition what percent of jobs run on 20% or more of the machine?

With 8-way GPU nodes costing about 1$million(ish) each, it does make me wonder what you do with small jobs? Do you allocate more than one job to a compute node? Better hope those jobs play nice with memory usage, network usage, etc. Are the software walls between jobs high enough to satisfy a user that the other won’t spy on them. (Have to protect from the prying eyes of foreign governments, or worse – competing academics who might scoop your publication)

A great deep dive into this latest Top500! It’s interesting also to note that Jupiter is the first Nvidia-powered machine to reach FP64 Exaflopping, which is a landmark, and should help further activate the competition in that space. Jupiter does this with 82% computational efficiency (Ceff = Rmax/Rpeak), the same as Fugaku, and is the highest in the top 10. I imagine some efficient networking (and/or GPUDirect?) is likely at play here.

The Blackwell-based CHIE-4 has Ceff = 89% which is outstanding at this scale (100+ PF/s) imho. El Capitan would crank out 2.5 ExaFLOPs if it could reach this efficiency. I have to think that this is where a key line is being drawn in the computational battleground, where a lot of competitive engineering is invested, and hopefully we see the results in upcoming MI430X and MI500 to keep the excitment coming! (the new #118 AMD-based Plasma Sim Subsystem B has 92% Ceff, but runs at just 16 PF/s rather than 100+)

For the MAXIMUS-384, it would be great if it could get even 70-80% Ceff (rather than its current 46%) and make an Rmax of around 200 PF/s. Harpia at #36 seems to be in a similar boat and should be able to get closer to 100 PF/s in time, with “tuning” (#28 ??? PowerEdge gives an idea of what is possible there I think).