A total addressable market is a forecast of what will be sold – more precisely, what can be manufactured and sold. It is not a forecast of aggregate demand, which can be even larger as the backlogs for HBM memory and its main propellant, GPU and XPU compute for AI inference and training, shows.

So when the TAM gets bigger, that means the revenues shared among competitors are also going to get bigger. And that is why the exploding TAM for HBM stacked memory by Micron Technology this week got everyone so revved up. Those of us outside of the walls of the major component consumers and their suppliers might not have a clear idea of what the total demand picture is AI compute and memory, but we just got a much better view on what the supply might look like.

“As the world’s leading technology companies advance toward artificial general intelligence and transform the global economy, our customers are committing to an extraordinary multiyear datacenter buildout,” Sanjay Mehrotra, Micron’s chief executive officer, said on the call with Wall Street analysts going over the financials for the company’s first quarter of fiscal 2026, which ended in November. “This growth in AI datacenter capacity is driving a significant increase in demand for high performance and high capacity memory and storage. Server unit demand has strengthened significantly, and we now expect calendar 2025 server unit growth in the high teens percentage range higher than our last earnings call outlook of 10 percent. We expect server demand strength to continue in 2026. Server memory and storage content and performance requirements continue to increase generation to generation.”

The boom is not just about HBM, of course, but includes other DRAM, LPDRAM, and flash memories that also go into AI systems. Mehrotra bragged that Micron’s datacenter NAND storage business had exceeded $1 billion for the first time in its history during Q1 F2026, and that the company’s G9 generation of flash is the first flash drive to adopt PCI-Express 6.0 and that the QLC variants of these devices, which have 122 TB and 245 TB raw capacities, are entering qualification at a number of hyperscalers and cloud builders.

Speaking very generally, industry bit shipments for DRAM are expected to be the low 20 percent range for calendar 2025, said Mehrotra, and will be in the high teens for NAND – considerably higher than Micron expected a quarter ago. And for calendar 2026, bits shipped are now expected to increase by around 20 percent for both DRAM and NAND compared to 2025. So any revenue growth above and beyond that is for an increase in price due to demand and other inflationary factors. In the first quarter of fiscal 2026, for instance, the cost per bit of DRAM rose by 20 percent and bits shipped were only up slightly; NAND bits shipped rose in the “mid-to-high single digit percentage range” but the cost per bit rose by the “mid-teens,” according to Mark Murphy, Micron’s chief financial officer.

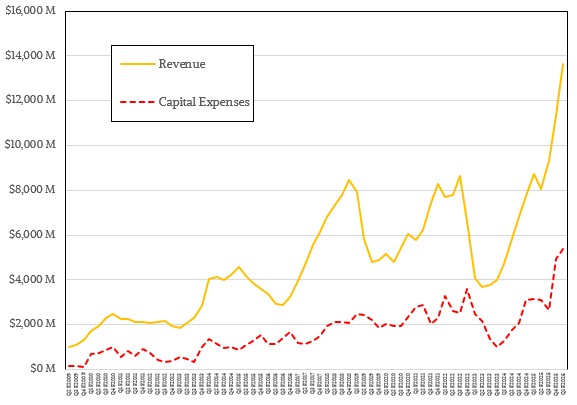

To help better meet 1-gamma DRAM and HBM memory supply, Micron is boosting its fiscal 2026 capital expenses spending by $2 billion to $20 billion, and is also speeding up equipment orders and installation times to get to etching more chips faster. The first fab in Idaho is also coming online in the middle of calendar 2027 rather than later in the second half of next year; a second foundry will be under construction starting next year and be up and running by the end of calendar 2028. The first foundry in New York will break ground in 2026 and be able to start supplying chips in 2030. An HBM packaging plant in Singapore will be contribute to HBM supplies in calendar 2027.

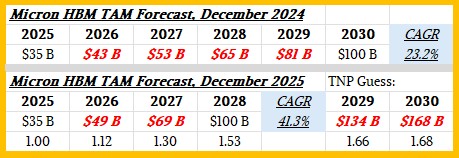

They had better ramp fast if Micron hopes to catch its share of the HBM TAM, which has just skyrocketed. Here is the forecast from last December, followed by the forecast just announced this week:

These TAMs for the HBM market are for calendar years – and it would be so much better if all companies also did their financials in calendar years. There is just no benefit to having fiscal numbers except habit and a desire for obfuscation.

In the December 2024 forecast, Micron expected for the HBM market to have $35 billion in revenues in 2025 and to grow to $100 billion or so by 2030. That is a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 23.2 percent. Now, Micron is pulling in that TAM estimate to hit $100 billion by 2028 instead of 2030, which is more than a 40 percent CAGR against the $35 billion in HBM sales expected this year.

The figures shown in bold red italics are out estimates to fill in the gaps, and more or less follow the CAGR sequentially and thus deliver the expected CAGR over the terms shown. We made a guess for HBM sales in 2029 and 2030, which Micron’s forecast did not, expecting it to level off to the rate that was originally expected. It could just keep going up at a higher rate – no one knows.

Here is the fun part. If you add up the total amount of memory over the six years of business from 2025 through 2030, inclusive, then in the December 2024 forecast you have $378 billion in HBM sold around the world. If Micron gets around 25 percent share of HBM revenues – about what it gets for DRAM sold today – then that is $95 billion to Micron for HBM over those years. If you assume that HBM memory is about 40 percent of the cost of a GPU or an XPU compute engine, that implies around $950 billion in GPU and XPU revenues over the six years, and if you assume that the accelerators represent around 65 percent of the costs of a node-scale or rack-scale server, that gets you to around $1.5 trillion in system revenues.

With the new forecast, and again assuming the growth rate of HBM revenue increases tapers off in 2029 and 2030, but growth is still pretty high at 35 percent in 2029 and 25 percent in 2030, that gets you $555 billion in HBM revenues over the six years, a 46.8 higher amount of revenues, and the gap in the forecasts is huge out towards the end. It is a lot more HBM being sold, which means a lot more HBM needs to be made. Micron would take in $139 billion or so in HBM memory over those six years if it holds to around 25 percent share, and that $555 billion in HBM would drive around $1.4 trillion in GPU and XPU compute engine production, which would in turn drive $2.1 trillion or so in AI system sales.

These numbers are a lot smaller than the total datacenter spending forecast that Nvidia quietly released a few weeks ago.

Those are admittedly some pretty rough estimates to get to AI system sales, but it is in a ballpark of some of the other big numbers that people are throwing around.

With that, let’s drill down into the Micron numbers for Q1 F2026.

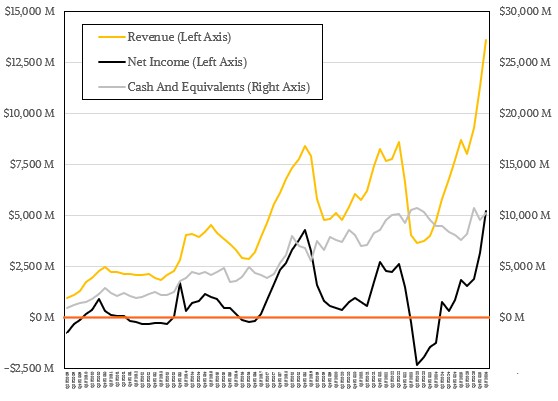

In the quarter, Micron had $13.64 billion in sales, up 56.7 percent. With operating income of $6.14 billion, up by a factor of 2.8X, and net income of $5.24 billion, also up 2.8X, it sure does look like an opportunistic pricing environment for main and flash memory.

Micron had $5.4 billion in capital expenses in Q1 F2026, a slightly bigger than proportional chunk of the $20 billion it expects to spend in fiscal 2026. That is a 1.7X increase over levels in the year ago period. Micron exited the quarter with $10.32 billion in the bank, giving it some maneuvering room as it expands its fabs and plants.

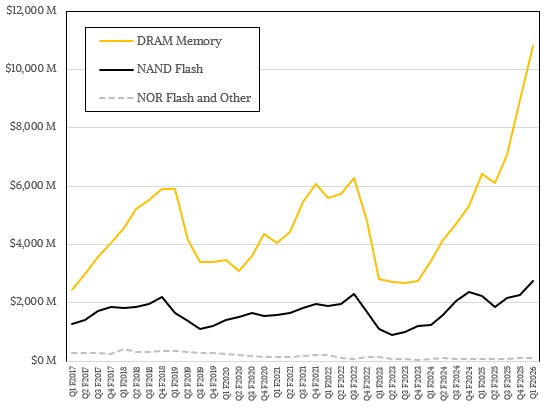

In the November quarter, Micron sold $10.81 billion in DRAM memory of all kinds, up 68.9 percent year on year.

NAND flash chips, drives, and cards accounted for $2.74 billion in revenues, up 22.4 percent, and NOR flash and other stuff drove a mere $88 million in sales in Q1 F2026.

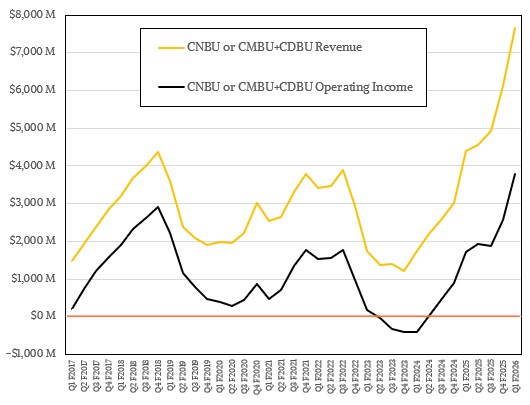

Here is how revenues break down on the new financial reporting groups that Micron announced a few quarters ago:

As you can see, the margins at both the Cloud Memory group and the Core Datacenter group both skyrocketed sequentially in Q1 F2026 compared to Q4 F2025, an indication of the tightness of the DRAM, HBM, and flash markets, which is driving up prices.

Add it all up, and the datacenter businesses at Micron drove $7.66 billion in revenues, up 55.1 percent, and operating income of $3.79 billion, nearly double from a year ago.

That boom-bust cycle for the datacenter memory business is scary, but for now it sure does look like it will boom times for the next year or two and will result in Micron setting very high new heights. Micron re-entered the HBM market at just the right time, and with just the right technical differentiation as well as the sovereignty of being headquartered in the United States.

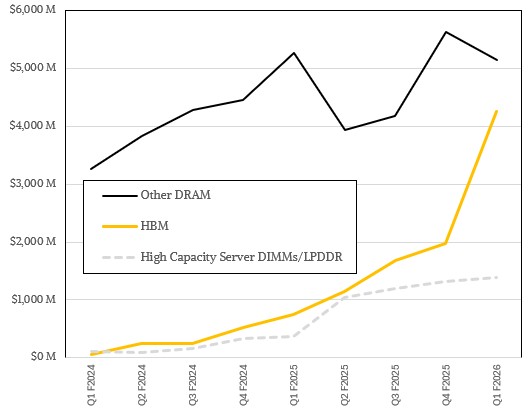

Our model suggests that HBM stacked memory plus high capacity server DRAM plus LPDDR5 low-powered server memory all together accounted for $5.66 billion, or a little more than half of all DRAM memory sold. That is more than a factor of 5X compared to the year ago period, and it is largely due to Nvidia using its HBM and LPDDR5 memory in its AI compute engines.

But lots of other companies are giving Micron money, too, with Nvidia only driving 17 percent of revenues in the quarter, amounting to $2.32 billion and double what Nvidia spent at the Micron Memory Store in the year ago period.

Our best guess – and it is an informed guess based on the relatively few statements that Micron makes over the past several quarters – is that high capacity server DIMMs and LPDDR5 memory drove around $1.4 billion in revenues, up 3.7X year on year, and HBM drove about $4.27 billion, up by 5.7X. This is crazy growth. But, then again, we live in crazy times – and they look like they are going to get crazier.

So one of the problems I have with articles like this is that they rarely go back and look at past estimates and how they actually stacked up to reality, and show the difference. So what did Micron predict one, two and three years ago and how do their actual numbers as filed with the SEC compare?

The idea is to get a better feel for how good Micron’s own look into the future really is, and how larger outside forces can steamroll them in both good and bad ways. It’s not as fun to go and look back at old numbers, but maybe it’s instructive to get a feel for whether they can be believed?

It’s great you’re cross-checking with other people’s prognostications and trying to get a better ballpark of what the numbers really look like. But how did they compare in the past? Is there a builtin house upside that never or rarely comes true? Or do they always lowball estimates so they can surprise the market in a good way?

I only started doing coverage on Micron from a financial perspective two years ago when it re-entered the HBM market in a big way. I am one guy trying to cover a lot of areas, and have to pick my targets to shoot at. But going forward, you can bet I will sure as hell be watching what they say now and how the next few years compare.