We have five decades of very fine-grained analysis of CPU compute engines in the datacenter, and changes come at a steady but glacial pace when it comes to CPU serving. The rise of datacenter GPU compute engines has happened in a very short decade and a half, and yet there is not, as far as we can tell, very good data that counts GPU compute by type and price band in the datacenter.

Some of this is due to the fact that the vast majority – in excess of 95 percent for the past four years – of datacenter GPU compute engines have come from one pretty secretive vendor: Nvidia. While Nvidia is reasonably good about divulging the feeds and speeds of its myriad devices, it is not forthcoming about which devices are being sold in what volumes into the datacenter.

There is also a misperception that the highest-end products like the “Volta” V100, the “Ampere” A100, and the “Hopper” H100 drive the bulk of Nvidia’s revenues and shipments for GPU accelerators that end up in servers. This, as it turns out, is not true. We don’t know how much it is not true, but we set out to try to figure it out.

We solicited some help from Aaron Rakers, managing director and technology analyst for Wells Fargo Equity Research as a starting point. Out of the same kind of frustration with the incomplete GPU data coming out of the usual suspects in IT market research – IDC, Gartner, Mercury Research, and others – Rakers did some digging and built his own model, which we are using (with permission) as the basis of doing some further prognostication about how the Nvidia GPU market in the datacenter will evolve as the company shifts to an annual cadence for GPU and CPU-GPU compute engine announcements and the world has what will likely be an insatiable appetite for GPUs for the next several years.

Here is how Rakers reckons that worldwide GPU shipments and revenues stacked up between 2015 and 2022, with extrapolations from 2023 out through 2027:

As you can see, between 2015 and 2022, datacenter GPU sales tracked very tightly with datacenter GPU shipments. AMD didn’t ship very many, and Intel was shipping the “Knights” Xeon Phi family of many core accelerators between 2015 and 2017. (Strictly speaking, these Xeon Phi devices were failed GPU cards that were turned into compute engines.)

And in 2022, the generative AI explosion hit and datacenter GPU revenues started growing a lot faster than constrained shipments. This is what happens when too much demand chases too little supply. And the model that Rakers has put together assumes that this impedance mismatch between supply and demand will continue out into 2027, which is why datacenter GPU sales, dominated by Nvidia with statistically significant contributions from AMD and Intel, will probably cross over $100 billion in 2028 if current trends persist.

By the way, the data above includes any GPU sold into the datacenter for any use, not just HPC and AI but also for video encoding, metaverse immersive simulation and virtual reality, and various other kinds of acceleration. And that means it not only includes devices that depend on interposer technologies, HBM stacked memory, and advanced substrates, but also lower-end devices that use GDDR memory and pack significant less compute but also cost significantly less. Rakers thinks that Nvidia will continue to dominate the GPU space out to 2027, as this monster table we copied from a presentation that Rakers put together and then did some analytical riffs upon:

In this table, we are calling any 100 series Nvidia GPU sold as a standalone PCI-Express card, an SXM module, or a CPU-GPU hybrid package a single GPU. We think that a Grace CPU probably adds somewhere between $10,000 to $15,000 to the cost of an SXM5 variant of a Hopper H100 GPU when it makes a GH200 Grace-Hopper superchip, and pricing on the Hopper GPU SXM package is somewhere between $30,000 and whatever you can afford – the Dell site had a $57,500 price tag on an H100 SXM5 device a few weeks ago, according to Rakers. That is not the money that Nvidia gets for the GPU, but rather the money that Dell gets. It is very hard to figure out how much Nvidia is charging OEMs, ODMs, and direct customers for the Hopper GPUs because we don’t precisely know the product revenue streams embodied in the Datacenter division or the Compute & Networking group at Nvidia.

Our main riff on this data is to try to figure out how many GPUs Nvidia shipped each year into the datacenter and what kinds, very generally in terms of those using CoWoS/HBM and those that are not, and how this might change as we project out into the future where Nvidia is going to have a broader product line and a faster annual cadence of product launches.

Like everyone else, we caught wind of the Nvidia datacenter roadmap that was released back in October 2023, buried inside of a financial presentation, and as you might remember, we tweaked that roadmap to remove some errors and to also put more precise times on past and future 200 series (CPU+SXM GPU), 100 series (SXM GPU), and 40 series (GDDR and PCI-Express GPU) launches as well as adding in “BlueField” DPUs, which are still on a two-year cadence. Here is that roadmap for your reference:

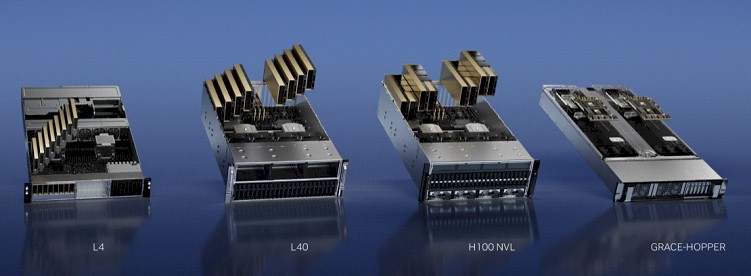

There are other datacenter GPUs – what we called the four workhorses of the AI revolution back in March 2023 – that are still sold by Nvidia, including the “Ampere” A40s, the “Turing” T4s and “Lovelace” L4s as well as the Hopper H100NVL double-wide units that were announced at that time at the GTC 2023 conference. As best as we can figure, in terms of unit shipments, these non-CoWoS/HBM devices dominate the shipments, and the CoWoS/HBM units dominate the performance and revenue across the Nvidia product lines.

But in our estimation, the CoWoS/HBM devices will comprise an increasing share of Nvidia’s GPU shipments, rising from somewhere around a quarter of units to around a third of units between 2022 and 2027, inclusive. That is our wild guess, which is shown in the bold red italics in the table above.

There are two things that are hard to project and that we all want to know – whether we follow the IT market or are a buyer of IT gear. The first is how long will each generation of each kind of GPU compute engine generation be actively sold, and the second is what price will these things sell at as compute, memory, and bandwidth capacity increases across those generations?

We assume a few things. First, each new process node and each new packaging technology gets more expensive, not cheaper, and therefore we believe that GPU devices across all product bands will get more expensive, not less so. So we expect that even as the future “Blackwell” B100 and the further future code-name unknown and perhaps variable X100 come into the field, the Hopper H100s (and the H200 is just a variant of the H100 with more HBM memory capacity and bandwidth) will still be in the field. Perhaps even out to 2027, when the 4 nanometer processes and current generation of CoWoS packaging and HBM3 memory will be mature and presumably less expensive than they are today – and therefore more profitable for Nvidia at the same price or at a lower price with the same profit margin.

We think that Nvidia will have a broadening product line with long-lived products that get cheaper over time, and that is why the average GPU price, as Rakers shows, will stay about the same going forward. That’s what we would do. Just like there are top-bin CPU parts that cost more than their relative performance compared to middle-bin or low-bin CPU parts, the same SKU pricing will hold for GPUs. The more advanced and compact and capacious a device is, the even more you will pay for it.

And competition from AMD, Intel, and others will not change this because they have no incentive whatsoever to start a price war. This is an extraordinary gravy train, and no one is going to try to derail it.

We wonder what the price bands will be, but there certainly is precedent for such banding in both PCs and servers over the many decades. For PCs, speaking very generally about laptops and rising into workstation-class desktops, the bands are around $250, $500, $900, $1,200, $1,700, $2,200, and $2,700. (We said roughly in terms of the banding.) For configured datacenter servers, configured X86 machines are in bands that are on the order of $2,500, $5,000, $8,000, $10,000, $20,000, $40,000, and on up from there. What you get in those price bands, whether you are talking PCs or servers, in terms of compute, storage, and networking, changes depending on the roadmaps and economics for the components in the system. But the goal of the OEMs and ODMs is to not change the price but what you get for the price. That allows us to form a habit: “Our servers cost $10,000 for a low-end machine and $20,000 for a high-end machine.” And then people stop thinking about the money so much.

CPUs already do such banding, too, and what you get for a given band changes over time. The Nvidia V100 was around $10,000 at launch, and so was the A100, but the H100 hit $30,000 and went up from there. And all GPU prices rose in concert from there as demand outstripped supply. We would not be surprised that CoWoS/HBM GPUs might settle into $10,000, $20,000, and $30,000 bands here in 2024, and future $40,000 and $50,000 bands will come out in future generations. Low-end devices used for inference and metaverse and other workloads will ship in much higher volumes with price bands that start at $1,500 and maybe go up to $2,500 then $5,000 then $10,000 and finally $20,000. (An L40S was at the Dell site for $20,000 a few weeks ago.)

What this means is that somewhen out in the future there might be a $1 million AI server node with sixteen GPUs and fully loaded with interconnect, memory, and compute.