There is a new tick–tock at work at chip maker Intel, and one that overlays the normal metronome cadence of manufacturing process shrinks and architecture advancement. This one is the tick of shipping products to hyperscalers, cloud builders, and a select few HPC centers and the other is the tock of shipping the same products one or two quarters later to enterprise and government customers.

For many quarters in a row, enterprises have been relatively tepid about spending compared to their hyperscaler and cloud builder peers. But not so in the fourth quarter of 2021, when Intel’s Data Center Group saw revenue from CPUs, chipsets, motherboards, and systems rise an amazing 53 percent year on year. To be fair, this was a reasonably easy compare against a 25 percent decline in Q4 2020, which was a pretty bad quarter all around for Data Center Group ahead of the “Ice Lake” Xeon SP server launch in March 2021. What this really means is that enterprise and government revenues for Data Center Group are only 14.8 percent higher in Q4 2021 than they were in Q4 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic hit.

The good news is that this big jump in spending among enterprise and government customers came just as hyperscalers and cloud builders – what Intel calls cloud service providers – was down 5 percent. They had already done a lot of their spending on Ice Lake Xeon SPs earlier in 2021. By the way, Q4 2021 spending by hyperscalers and cloud builders for Data Center Group were still 19.3 percent lower than spending on Q4 2019. Sales of chippery, boards, and systems to communications service providers – meaning telcos and other smaller tier cloud builders and hosters – were up 22 percent in Q4 2021, which also helped.

And we know what you might be thinking: Does this enterprise and government revenue bump have something to do with the “Aurora” supercomputer being built by Intel and installed at Argonne National Laboratory? As far as we know, it does not, and that is because Intel can only recognize revenue when a supercomputer is accepted and, again, as far as we know, the Aurora machine is not built yet, much less accepted. In fact, as we have previously reported, Intel Federal, which is the part of the chip maker that is the prime contractor for the Aurora machine, was set to take a $300 million writeoff in the quarter which adversely affected Data Center Group profits, and we think this writeoff is related to Aurora but the company has been very stubborn about not answering the question directly. (The machine has been delayed many times, and we suspect there are penalties for this.)

We suspect that some of the enterprise and government spending bump that Intel is seeing has to do with some building up of inventory by the IT channel as supply chain shortages, for everything from network interface cards to special power circuits on motherboards, have been delays in server shipments. They might be trying to get ahead of the curve, which is necessary when the hyperscalers and cloud builders are the tick, the enterprise and government customers are the tock, and the comm service providers are somewhere in between.

In the quarter, Data Center Group server chips, chipsets, and motherboards accounted for $6.44 billion in sales, up 21.6 percent year on year, and adjacencies such as system sales and networking, accounted for $864 million, up 9.2 percent. Add them up, and Data Center Group posted $7.31 billion in overall sales, up 20 percent, but operating income fell by 16.9 percent to $1.73 billion. That hit to operating income includes the cost of ramping 10 nanometer manufacturing and its follow-on 10+ nanometer process, called Intel 7, and its 7 nanometer processes, called Intel 4 (5 nanometer-ish), and its roadmap development for the future Intel 3, Intel 20A, and Intel 18A processes.

We are still getting used to the new naming conventions, so here they are again as a reminder:

In a conference call with Wall Street analysts, chief executive officer Pat Gelsinger said that Intel had shipped more Xeon chips in the month of December than the total number of server shipments “by any single competitor for all of 2021.” Gelsinger is talking about you, AMD, and he added that in Q4 2021, Intel shipped more than 1 million units of the Ice Lake Xeon SPs, which was equal to the shipments in the prior three quarters of 2021 (including the first quarter, when only the hyperscalers and cloud builders were getting them ahead of the official launch). That’s more than 2 million Ice Lake Xeon SPs, and that probably works out to slightly more than 1 million servers. (Ice Lake Xeon SPs are only available in machines with one or two sockets, and there are some single socket nodes being sold out there.)

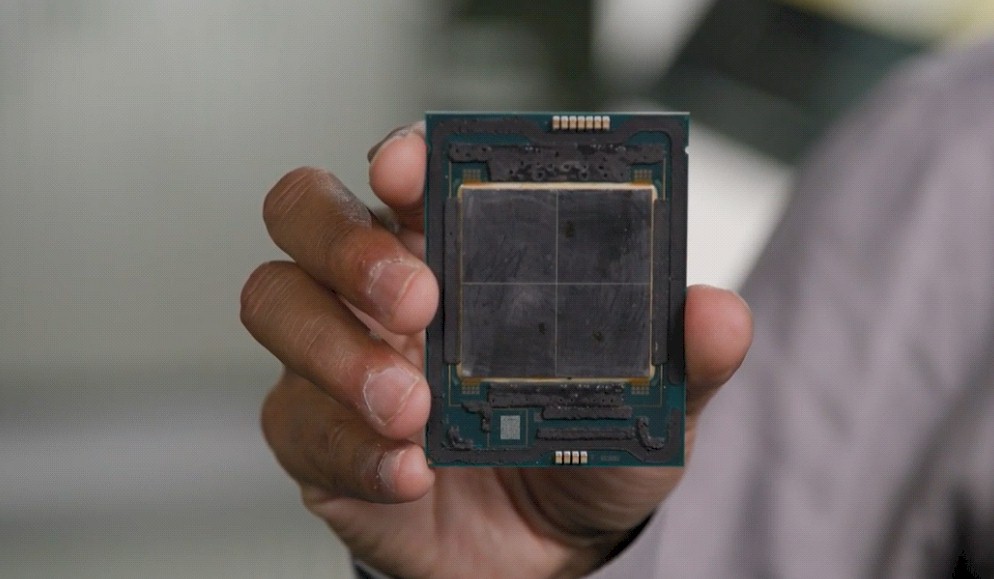

Gelsinger reiterated that it the company would begin shipping its initial “Sapphire Rapids” Xeon SPs, based on the updated 10 nanometer SuperFIN process (now called Intel 7), in the first quarter – again, very likely to hyperscalers and cloud builders ahead of the expected second quarter official launch of these chips. There has been rumors that the Sapphire Rapids ramp had slipped to the third quarter, but Intel told us last week that the Sapphire Rapids chip was on track for a ramp beginning in the second quarter.

We think that at least some of Intel’s gain with Ice Lake Xeon SPs is because AMD and Ampere Computing, who use Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co as their foundry, cannot get enough of their respective Epyc and Altra processors made to meet demand. But that is just a hunch. What we do know is demand and supply is all kinds of difficult, and Gelsinger said as much as he contemplated Intel’s next couple of years in datacenter compute.

“This unprecedented demand continues to be tempered by supply chain constraints as shortages in substrates, components, and foundry silicon has limited our customers’ ability to ship finished systems,” Gelsinger explained. “Across the industry, this was most acutely felt in the client market, particularly in notebooks, but constraints have widely impacted other markets, including automotive, the Internet of Things and the datacenter. As we predicted, these ecosystem constraints are expected to persist through 2022 and into 2023, with incremental improvements over this period. The industry will continue to see challenges in a variety of areas, including specialty and overall foundry shortages, substrates as well as third-party silicon.”

We think there are constraints, and we also think that chip makers love when demand exceeds supply because they can charge a premium.

As for the competition between AMD and Intel, Gelsinger had this to say: “We do expect that there’s going to be a bit of to and fro with the competitive alternatives, where they will deliver a product, then we will deliver the next product. And as you have heard me say, we are on a path to sustained unquestioned leadership into this area. It’s going to take us a few generations until we’re unquestionably in a leadership position. But we believe our product teams, our packaging teams and our process technologies, our factory capacity, all of these give us the tools to create leadership products. And then we combine that with our platform leadership and our software technologies, we have a path to unquestioned leadership over time.”

We shall see. We plotted out a Xeon SP roadmap out to 2025 or 2026 that shows it can use architecture, process, and packaging to make some very powerful server chips.

Data Center Group does not encapsulate all datacenter revenues that Intel generates, and we try to suss out what the revenue and profit streams across all of Intel. Here is the latest model, including Q4 2021:

And for those of you who like the raw data, here it is for the last two years:

Including sales of server chips, chipsets, motherboards, and systems, plus network switches and interface cards, IoT edge systems based on servers, flash and Optane memory, and FPGAs, we reckon that Intel’s “real” datacenter business came in at $9.12 billion, up 16 percent, and operating profit was $2.21, down 3 percent.