While a $1.25 billion hit to the Nvidia books after the company terminated its $40 billion deal to acquire chip designer Arm Holdings from Japanese conglomerate SoftBank Group this week is a big deal, the fact that Nvidia and SoftBank were going to see a lot of regulatory scrutiny and IT market resistance is no surprise. And thus, neither is the announcement that the deal had collapsed and SoftBank is going to re-take Arm Holdings public sometime before March next year.

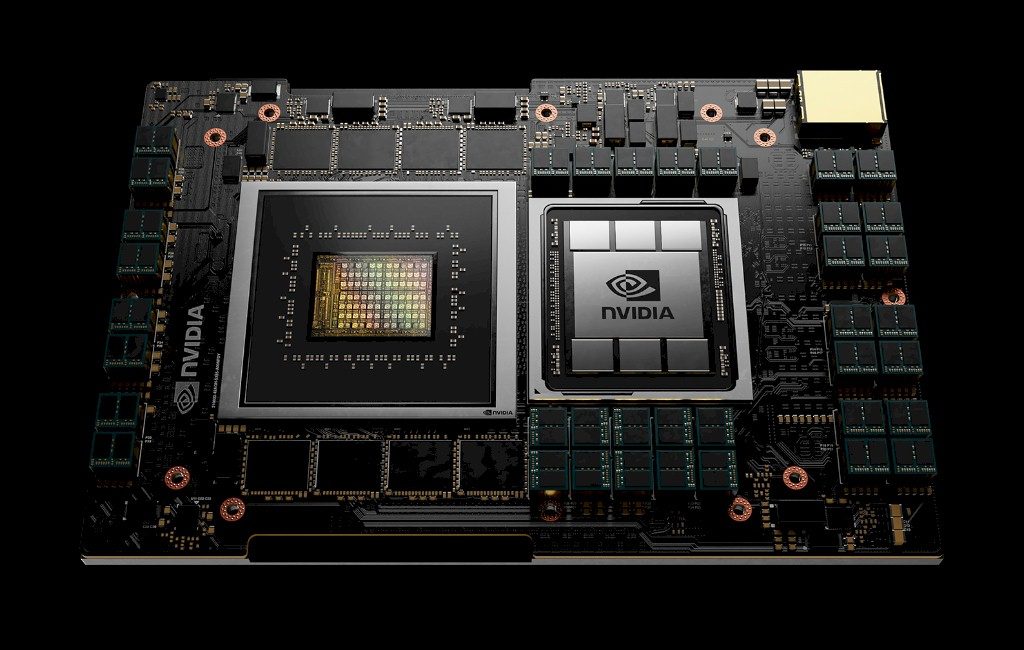

While we were hopeful that Nvidia would be a good steward for the Arm architecture, like many, we were perplexed why Nvidia, which is an Arm architecture licensee and which has sold Tegra embedded CPUs based on Arm designs for many years and which is getting set to bring its first Arm server chip, code-named “Grace,” to market next year, needed to go all the way and buy Arm Holdings.

Months before the Arm acquisition was announced in September 2020, the rumors were swirling around and we did our usual thought experiment as to why this might happen, and we were skeptical about the deal and suggested then, as we do now, that just because Nvidia liked the razor it did not have to pull a Victor Kiam and buy the whole company. And we said as much when we talked to Nvidia co-founder and chief executive officer Jensen Huang a few weeks after the deal was revealed.

The fall of 2020 seems so long ago, but back then we tore the deal apart and figured that shelling out $12 billion in cash, issuing another $21.5 billion in stock, issuing a $5 billion performance bonus to SoftBank, and issuing another $1.5 billion in Arm stock to retain key employees at the company – Arm Holdings has a lot of key employees – was nowhere as expensive as Nvidia forking over $40 billion in cash to SoftBank, which Nvidia did not have in the bank at the time and does not have today, either.

At the time the deal was announced, Nvidia had $10.1 billion in cash after just paying $6.9 billion a few months earlier to buy network chip and gear maker Mellanox Technologies and had a market capitalization of just over $300 billion. When the deal was done, Huang and team no doubt figured there would be a lot of regulatory hurdles, which would take time, and as happened in the Mellanox deal, by the time Nvidia got to the Arm Holdings deal closing, it would have a much bigger pile of cash and a much higher stock valuation. Nvidia reports its Q4 F2022 financial results next week, so we don’t know how much cash it has, but at the end of Q3 F2022, the company had $19.3 billion in the bank and SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son no doubt wished he had asked for more cash and less stock to do the deal. Or maybe more cash and more stock, given that Nvidia had a market capitalization of $658 billion last week before rumors of the deal coming unwound hit Wall Street. Because of the appreciation in Nvidia stock in the past year and a half, the value of the deal had grown to $66 billion before the two companies pulled the plug on it.

Obviously, under the deal Nvidia originally negotiated, it could swallow Arm Holdings whole and not even burp afterwards. But having Nvidia in control of what is still essentially a British chip company – and the standard bearer of decades of innovation that aptly demonstrates Great Britain can still contribute mightily to the IT sector – and in control of the licensing of Arm technology caused great consternation among the other Arm licensees – not to mention more than a few national governments. There was not so much fuss made about SoftBank paying $32 billion to acquire Arm Holdings back in July 2016 precisely because SoftBank was not a licensee of Arm’s technology, but rather a holding company making an investment, although there was some griping about ownership of Arm outside of the United Kingdom.

The point is, Nvidia has to do something with all of that market capitalization and its cash as it builds up, and it has to be more useful than just returning it to shareholders. It needs to invest in the future and get a higher return on that cash. And we think Nvidia will be on the prowl for acquisitions now. And this time around, it will have more to do with artificial intelligence and the Omniverse than it does with being a chip design supplier to the world’s clients and an increasing number of servers.

While Arm Holdings certain created the dominant architecture for smartphones and tablets and is seeing uptake at the edge, in PCs, and in servers, the company was not generating as much revenue and profit relative to its market value, based on the SoftBank acquisition and the now defunct Nvidia acquisition, as you might think. But the revenue and profits are both on the rise, as Masayoshi showed in reporting the financial results for Softbank yesterday, including a forecast for fiscal 2021, which will end in March of this year:

This, said Masayoshi, has been a V-shaped recovery for Arm, and it really did not look that good when the Nvidia deal was announced only a year and a half ago. Thanks to the uptake of Arm architectures in Apple PCs, Amazon and Ampere Computing server chips, and expansion into automotive compute and acceleration, the royalty money and licensing money is rolling in and boosting the business as these chips are produced in higher and higher volumes as the usual suspects in smartphones, tablets, and IoT devices that have depended on the Arm architecture from the beginning.

When talking about the Arm Holdings deal with us, Huang made it clear that Nvidia did not need the Arm deal to succeed to be successful.

“Our company can realize all of our hopes and dreams without Arm,” Huang told The Next Platform, and added that it has taken three decades for Arm and Nvidia to build their respective engineering teams and that “this is a team that won’t get built again” to emphasize the unique opportunity.

One thing we know for sure is that in the wake of this, Nvidia will next year deliver an Arm-based server chip, something it has been talking about doing since it unveiled “Project Denver” back in January 2011 when Arm servers first took off as an idea with commercial possibilities. Denver was going to be a beefy GPU with beefy Arm CPU cores on it, not a free-standing GPU like Grace will be. And we think that Nvidia’s engineers will have lots of interesting twists in their architecture, as the future (unnamed) server chips from Ampere Computing will, as the current Graviton3 chips from Amazon Web Services do, and as the current A64FX processor for supercomputers does from Fujitsu. We are convinced that the combination of Nvidia CPUs and GPUs will demonstrate the state of the art in hybrid computing.

That may not be as exciting as steering the vastness of the Arm architecture ecosystem, which shipped 22 billion chips in 2019 (the year before the Nvidia deal was announced) compared to 100 million chips for all of Nvidia.

But there is another interesting option that Nvidia could do. Back when the Arm Holdings deal was announced, Huang made it absolutely clear that Nvidia intended to preserve Arm Holdings as an intellectual property powerhouse protected by British law, with a center of gravity in the United Kingdom, and told us that once the deal closed, Nvidia would push all of its technologies – GPUs, network switch and adapter ASICs, as well as CPUs – through the Arm intellectual property channels to be licensed.

Just because this deal has fallen apart because of regulatory issues and the concerns of licensees that Arm Holdings remain independent of conflicts of interest does not mean that Nvidia cannot do a joint venture partnership with Arm Holdings and push its GPU and network chips through the Arm licensing machine and make them all licensable to existing and future Arm licensees. Imagine if you could license and modify Nvidia GPUs and Ethernet or InfiniBand switch ASICs. . . .

Many of the benefits that Nvidia was seeking through ownership can be brought to bear through partnership. It remains to be seen if this will happen, or if the two parties are even thinking this way. But if Microsoft can join the Open Compute Project and have its own server designs opened up to create an ecosystem of suppliers that is distinct from those of Facebook, then Nvidia could make its own GPU, switch, and adapter chips licensable through the Arm Holdings machine. Why not?