Microsoft is not just the world’s biggest consumer of OpenAI models, but also still the largest partner providing compute, networking, and storage to OpenAI as it builds its latest GPT models. And that gives Microsoft two reasons to build a better Maia AI accelerator, which it has just announced that it has done.

All of the big clouds and hyperscalers plus three of the four big GenAI model makers – OpenAI, Anthropic, and Meta Platforms – are all trying very hard to create their own custom AI XPUs so they can lower the cost per token for GenAI workloads running inference. xAI, the fourth indie model builder, looks poised to use whatever Tesla might develop with Dojo, should it be scalable enough and adaptable to the GenAI training and inference tasks, but seems content with Nvidia GPUs for the moment.

Training is something a few players are still interested in tackling, but really, Nvidia pretty much owns this market and with AI inference in production at companies and governments around the world, either directly or indirectly through clouds, expected to require perhaps an order of magnitude more compute than AI training, there is a chance for the over a hundred AI compute engine startups to carve a niche and make some money.

Microsoft, like all hyperscalers, wants to control its own hardware fate as it deploys copilots powered by AI, but being a cloud it also has to keep general purpose X86 CPUs and Nvidia GPUs around (and to a growing extent, AMD GPUs as well) so customers will rent them if this is their architectural preference. Like other clouds, Microsoft is happy to charge a hefty premium for those who want to use AMD or Nvidia GPUs or Intel or AMD or even Nvidia CPUs. But it also wants to make its own compute engines and undercut the price compared to these third party alternatives. This way, when you rent a Cobalt CPU or a Maia XPU, you are actually underwriting Microsoft’s independence from these chip suppliers.

The same logic holds for Amazon Web Services, Google, Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and a handful of others designing their own CPUs and XPUs. Meta Platforms is not precisely an infrastructure cloud, but as it is renting out capacity on its iron to run Llama model APIs much as OpenAI and Anthropic do with their respective GPT and Claude GenAI models, it is becoming a GenAI platform cloud for various kinds of sovereigns – and is seeking their money to build the infrastructure that must underpin its “superintelligence” aspirations.

Google started its Tensor Processing Unit effort more than a decade ago because it knew it could not roll out AI-assisted voice search on Android devices for a mere three minutes a day without having to double the capacity of its datacenters. Microsoft had its “oh shit. . .” moment a few years back as its partnership with OpenAI really took off and its usage of GPT looked like it was going to hockey stick to Pluto. And hence it divulged the “Athena” Maia 100 XPU in November 2023 with very few details and some rack photos.

The Maia 100 chip was designed to support both AI training and inference, and was explicitly designed to run OpenAI’s GPT as a backend for Microsoft’s OpenAI API services and its copilots. There was some chatter that this did not happen and that the Athena chip was actually not very good at this, but we don’t put much stock in this. However, it is suspicious that there never was an Azure VM instance with Maia 100 accelerators for rent. Perhaps OpenAI didn’t want to deploy its training or inference work on Athena chips, so Microsoft did not ramp up the volume.

This does not look like it will be the case with the “Braga” Maia 200, the successor to the Athena that is aimed solely at AI inference, which simplifies the design a bit.

To get a sense of what Maia 200 is, we need to go back and dig around for information about the Maia 100, which was not available at launch and which has been dribbed and drabbed out over time.

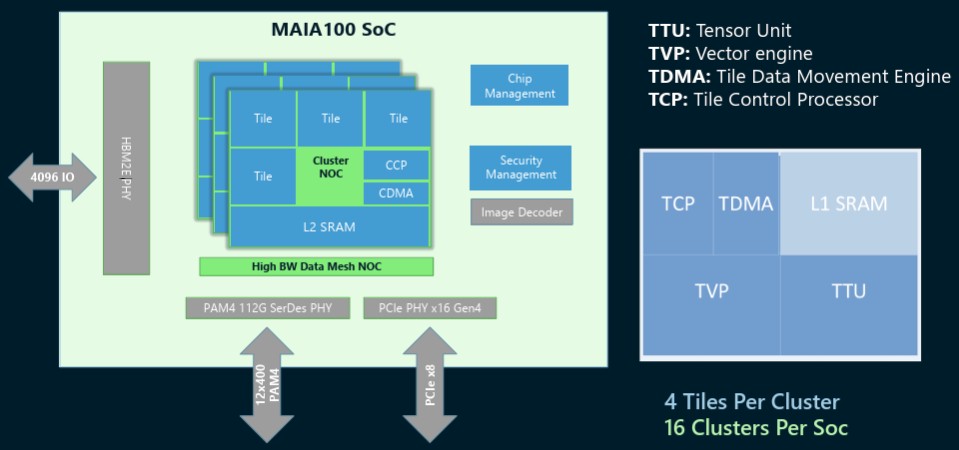

Here is what the Athena Maia 100 chip looked like:

You can see the four banks of HBM stacked memory outlined in the package.

Each Athena core has a tensor unit and a vector unit, which are respectively labeled Tile Tensor Unit (TTU) and Tile Vector Processor (TVP, and not texturized vegetable protein). There is a control processor that manages the flow of work through the Athena core, and a Tile Data Movement Engine that coordinates the movement of data across collections of the L1 caches on each tile. These tiles are aggregated into what Microsoft calls a cluster. (We would call them cores and a streaming processor, and collections of clusters would make a compute engine.)

There are four tiles in a cluster, as shown above, and each cluster has its own Cluster Control Processor (CCP) and Cluster Data Movement Engine (CDMA) that manages access into the L2 cache SRAM.

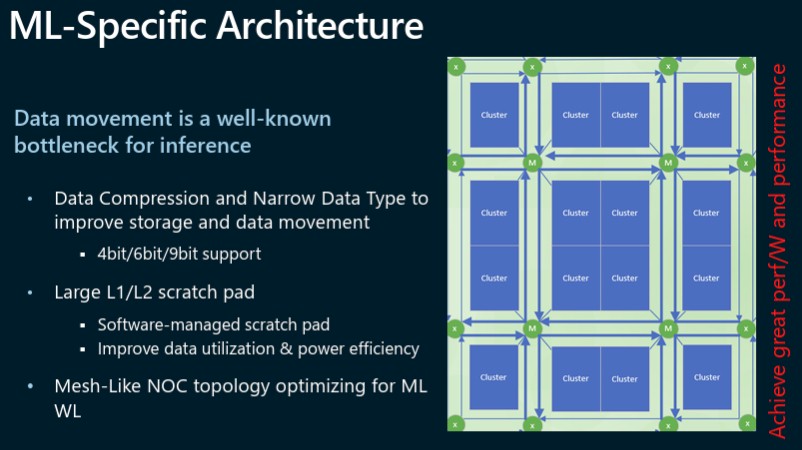

Microsoft never did divulge how much specific L1 SRAM was one each tile and how much L2 SRAM was shared across four tiles in a cluster, but it hinted that it was around 500 MB when you added up all of the L1 and L2 cache on the whole Athena compute engine. That compute engine had a total of sixteen clusters, interconnected using a 2D mesh, for a total of 64 of what we would call cores. Like this:

We think the Athena chip had 64 cores, as shown, but we don’t know what the yield was on those cores and therefore what the effective performance was for a real Maia 100. We have a hard time believing that it had anything close to 100 percent yield. Somewhere between 52 cores and 56 cores seems likely, as we assume the performance numbers that Microsoft gave out were for perfectly yielding parts.

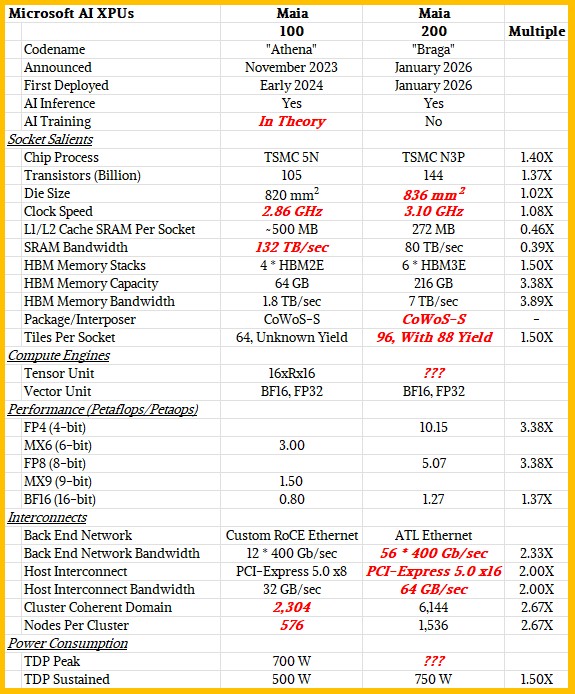

The Athena chip was, at 820 mm2, pretty close to the reticle limit for the 5 nanometer process from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Microsoft said eventually that the Athena chip complex had 105 billion transistors, and it looks like a monolithic die but that has not been confirmed. We think the Maia 100 clocked in around 2.86 GHz, and we estimate that that 500 MB or so of aggregate SRAM on the chip had an aggregate bandwidth of 132 TB/sec. The four stacks of HBM2E memory on the Athena compute engine had 64 GB of capacity and 1.8 TB/sec of bandwidth – not all that great for even two years ago.

The tensor unit on each Athena core supported Microsoft’s own funky MX6 6-bit and MX9 9-bit formats, which use microexponents that have slightly higher precision than FP4 and FP8 formats without too much of a hit on throughput thanks to hardware-assist functions in the Maia cores. The MX9 format was supposed to be used for training (it replaces BF16 and FP32 format with less hardware overhead) and the MX6 format was aimed at inference, which is how we know Microsoft was aiming for both kinds of AI workload with the Athena chip.

As cool as these MX9 and MX6 formats created by Microsoft and Meta Platforms were, the only chip to ever implement them was the Maia 100. And it is not clear if OpenAI was thrilled about these, either. Perhaps not, because the Braga Maia 200 chip just does FP4 and FP8 on the tensor units and BF16 and FP32 on the vector units.

The Maia 100 did not just have a lot of SRAM bandwidth and fairly high SRAM capacity, it also had a lot of I/O bandwidth for interconnects – at least for a chip using Ethernet as its underlying interconnect transport, anyway. The Maia 100 had a dozen ports running at 400 Gb/sec to deliver an aggregate of 4,800 Gb/sec (600 GB/sec) into each Athena compute engine, which is two-thirds of what an NVLink port has going into a “Hopper” H100 or H200 GPU or one of the pair of “Blackwell” B200 or B300 chiplets in a Blackwell socket.

This is not all implemented as a single, aggregated port, however. Nine of the twelve lanes are allocated to chip-to-chip links between one Athena chip and the three others in a four-way quad that is the baseboard for Athena systems. The other three remaining ports are split up across three different rails of interconnect that provide 150 GB/sec of bandwidth out to other Athena quads in a system. Packets are sprayed across those three rails to cut down on congestion. By our math, it looks like a coherent cluster domain for the Maia 100 was 576 nodes with a total of 2,304 compute engines – not too shabby for a glorified Ethernet network.

With the Maia 200, as you can see in the salient characteristics table below, this glorified RoCE Ethernet has been tweaked some more and is now called the AI Transport Layer and it is implemented on an integrated network interface, just like the NIC was in the Maia 100 compute engine. The difference is that the ATL network has eight rails for even more packet spraying and for an even larger cluster domain of 1,536 nodes and 6,144 compute engines.

We think this integrated NIC has 56 lanes of SerDes running at 400 Gb/sec, which delivers 2.8 TB/sec of aggregate, bi-direction bandwidth into and out of the Maia 200 chip. As before, we think that nine of those 56 lanes are used in the all-to-all links to make a Braga quad system board. The remaining 47 lanes are used to implement the eight rails of the ATL interconnect. Exactly how these are arranged for packet spraying and linking into a two tier Ethernet network for a scale up memory domain is unclear, but when we get a moment we will try to work it out.

With the Maia 200, Microsoft is stepping up to TSMC’s N3P performance variant of its 3 nanometer process to etch the chip. Thanks to that shrink, we think Microsoft could boost the clock speed by 8 percent to 3.1 GHz, and could increase the area of the chip by 2 percent to get to 836 mm2, which is that much closer to the 858 mm2 reticle limit of current lithography methods. Most of that shrink, however, was used to get 144 billion transistors on the chip, which had the most direct impact on the relative performance between the Athena and the Braga chips.

While the I/O bandwidth went up by a factor of 2.33X between Athena and Braga, the SRAM capacity per compute engine was more than cut in half and we estimate that the aggregate SRAM bandwidth went down by 61 percent even as the number of cores went by 50 percent, according to our estimates, to 96 cores. We think the yield of Braga cores is around 92 percent, which would yield 88 usable cores in the mainstream parts.

While the transistors went up by 1.5X, the HBM memory capacity went up by 3.4X to 216 GB (six stacks of twelve-high 3 GB chips for 36 GB per stack) and memory bandwidth went up by 3.9X to 7 TB/sec thanks to having two more stacks and to moving to HBM 3E memory. (From SK Hynix, as it turns out.)

Microsoft has not released technical specs or block diagrams on the Braga chip as yet, but we do know that it is rated at 10.15 petaflops at FP4 precision and 5.07 petaflops at FP8 precision on the tensor units and at 1.27 petaflops at BF16 precision on the vector units. All in a 750 watt thermal envelope.

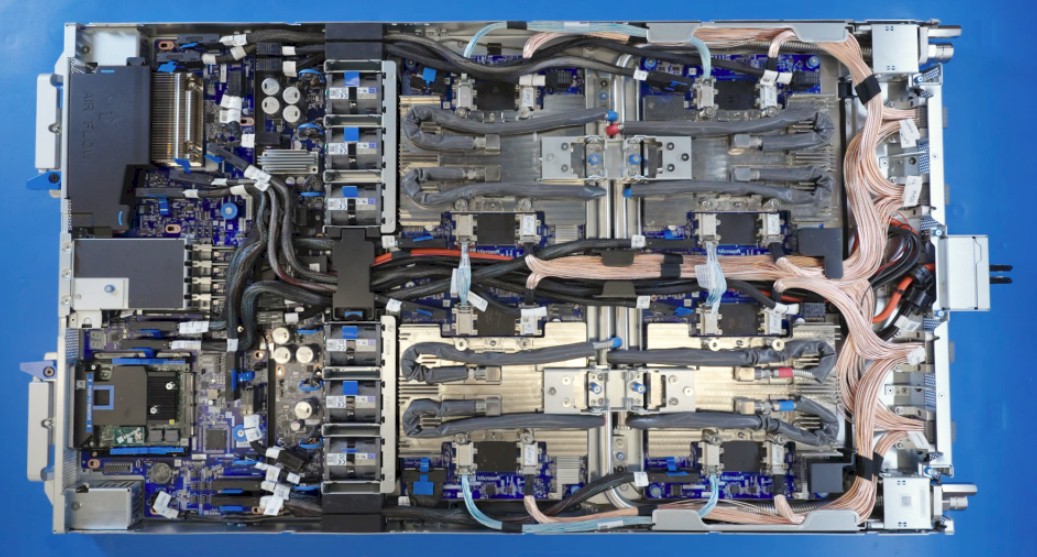

Here is what a Maia 200 blade server, which has four AI XPUs on the right and what looks like one CPU – very likely a single Cobalt 200, which was unveiled last November and which has about a 50 percent boost in performance over the prior Cobalt 100 chip made by Microsoft.

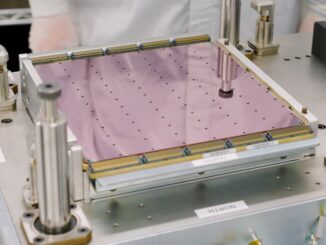

And finally, here are some racks. Here is an empty pair of Maia 200 racks with a coolant distribution rack on the left:

And here are some half populated Maia 200 racks in Microsoft’s Azure datacenters:

The US Central region of the Azure cloud, which is located outside of Des Moines, Iowa has Maia 200 racks right now, and the US West 3 region outside of Phoenix, Arizona will get them next. Microsoft says that it will use the Maia 200 compute engines to serve inference tokens for the OpenAI GPT-5.2 large language model, driving the Microsoft Foundry AI platforms as well as Office 365 copilots. AI researchers at Microsoft will also use the Maia 200 to generate synthetic data for training in-house models.

No word on when Azure will rent VM instances based on Maia 200, which would let techies put them to the test on all kinds of AI models.

Be the first to comment