For nearly two years the world has been coping with the coronavirus pandemic, and it has had obvious and consequential effects on the market for hardware, software, and services in the datacenter. Some of this has been good for business, some of it bad, and a lot of it has been a mixed bag. Shortages plague all parts of the supply chain, but vendors can command a premium just like chip makers do, which cushions the blow a bit.

With each passing decade, information technology has become more entrenched in business, and today it is to the point that you can accurately say that for a very large portion of the economy, the systems that encapsulate the operations of businesses and provide the interactions with suppliers and customers that make goods and services move throughout the economy are the business. Without them, there is no business.

And so spending on IT wares and the services that enable and support them as well as the telecommunications that hooks systems to each other and people to each other and to systems continues to grow. But starting in 2022, it looks like the priorities are going to shift from dealing with all of the changes compelled by the pandemic back to worrying about how to grow and transform companies to run and expand current businesses and create new opportunities.

“2022 is the year that the future returns for the CIO,” explains John-David Lovelock, the distinguished research vice president at Gartner who puts out the annual IT spending forecasts for the market researcher. “They are now in a position to move beyond the critical, short-term projects over the past two years and focus on the long term. Simultaneously, staff skills gaps, wage inflation, and the war for talent will push CIOs to rely more on consultancies and managed service firms to pursue their digital strategies.”

If you are an IT consultant gunslinger, then the next four years are apparently going to be a boom time for you, according to Lovelock, at least for those who are working for large enterprises. The high demand for IT talent among the established internet companies – particularly the hyperscalers and cloud builders, but not limited to them – and countless startups is going to create a rush for IT talent, and Lovelock says that is going to force a lot of companies to hire outside consultants to do a lot of the heavy lifting with digitization and modernization projects, and developing an effective – and very likely hybrid – cloud infrastructure strategy. The same booms happened with ERP software back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and is happening with AI and cloud technologies right now.

That sets the broader themes against which IT spending is done, but let’s face it, a lot of money is spent on the infrastructure and systems software to run existing applications, which have their usual expansion rate alongside the growth in business and the ever-more-complex nature of transactions, including front-end recommendation engines and a slew of back-end analytics to squeeze more revenue out of each transaction.

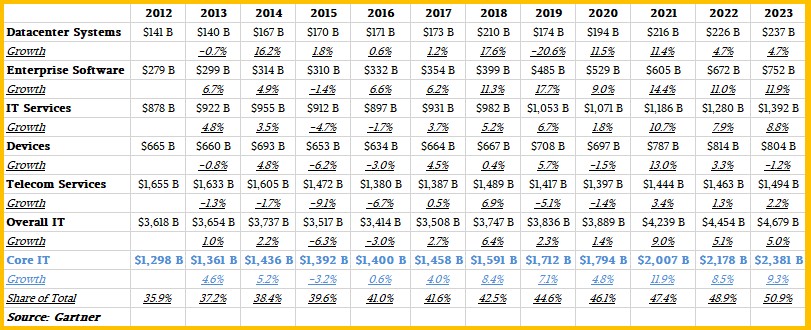

It is a very bad thing when IT spending goes down because it takes some time and some confidence in the future to build momentum up again. We have been tracking Gartner’s IT spending prognostications for more than a decade, including updates that come out a couple of times a year, and here is a snapshot of spending between 2012 and 2021, with forecasts as of this month going out into 2022 and 2023:

In the table above, datacenter systems is the aggregate of servers, storage, and switching sold into the datacenter, and Gartner is eliminating double-counting that can happen when servers are used as storage arrays or storage arrays embed switching. As far as we are concerned, this is the most interesting bit of the IT spending chart, since we believe that hardware spending is a kind of leading indicator of software spending (both that which is licensed and that which is created) and services spending (for hardware and software support as well as systems integration and other necessary work). To be very precise, hardware spending is an indicator of the amount of spending companies are doing to buy or develop enterprise software, probably several months to a year in advance. And with the advent of clouds and a more or less annual server update cadence, it is a measure of the expected capacity demands that clouds expect customers to have maybe 12 to 18 months into the future.

Enterprise software spending is exactly what you think it means, but this is only for software bought under subscriptions and licenses; it does not include the value of homegrown software, of which there has always been a lot across large enterprises and which represents the bulk of software spending among the hyperscalers and cloud builders. We don’t have any way to quantify the “spending” on homegrown software, but it would be a very interesting piece to snap into this Gartner model.

What we can tell you is that the ratio of software spending to hardware spending in the enterprise (excluding PCs, smartphones, and tablets that are counted separately in the devices line item in the Gartner data) has been on the rise in the past decade. Back in the early 2010s, it averaged under 2.0, and here in the early 2020s, it is now averaging over 3.0. It illustrates a principle, we think, that we have been espousing for some time, and that is that hardware pricing and capacity are subject to Moore’s Law price/performance improvements, which lowers the cost of a unit of capacity over time, while software is subject to inflationary pressures because it is created and maintained by people, who tend to cost more every year for delivering the same pace of innovation. It is hard to extract this inflationary effect on software from the cost of automating more parts of the business (which also tends to increase the software budget) and paying for more sophisticated software (such as upgrading from an old, homegrown ERP or CRM system to one made by Oracle or SAP). But there is no question that it is in the equation.

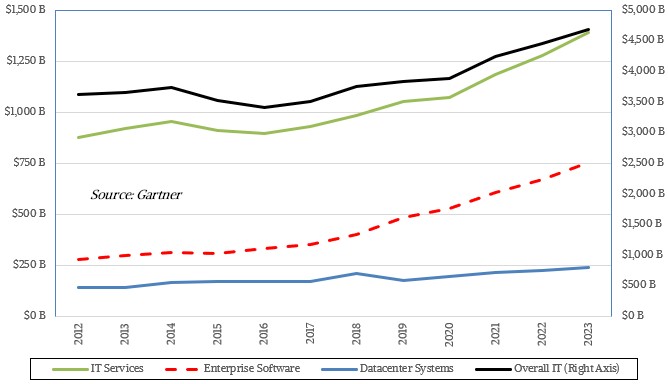

Not only is the amount of spending on enterprise software larger than for datacenter hardware, it is growing faster. And so is spending on IT services for that matter. You can read the data in the table above, but this chart makes it easier to see the different growth rates:

Add these three items together and you get what we are calling the core IT spending in the datacenter, and generally speaking this part of the market grows between 3 percent and 5 percent faster than the overall IT market, which includes not only the end user devices mentioned above but also a very large budget for various kinds of telecom services used to back businesses.

The other interesting thing to see in the data above is that core IT spending is becoming an increasingly large portion of the overall IT spending globally. Back in 2012, core IT was 35.9 percent of the total $1.3 trillion IT pie on Earth, and in 2023 it is anticipated to represent 50.9 percent of the $2.38 trillion in overall IT spending.

No matter the difficulties of the supply chain and the disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic, datacenter systems spending, propped up by the buying of hyperscalers and cloud builders, kept roaring in 2020 and 2021, according to Gartner’s data. And this year, Gartner is projecting that datacenter systems spending will rise by a much leaner (and normal) 4.7 percent to $226.5 billion and will rise again by 4.7 percent in 2023 to hit $237 billion. Core IT spending, including enterprise software and IT services added to datacenter systems spending, will rise by 8.5 percent to $2.18 trillion in 2022 and by another 9.3 percent to $2.38 trillion in 2023. Software and IT services growth will be higher than datacenter systems growth as it has been in the past several years.

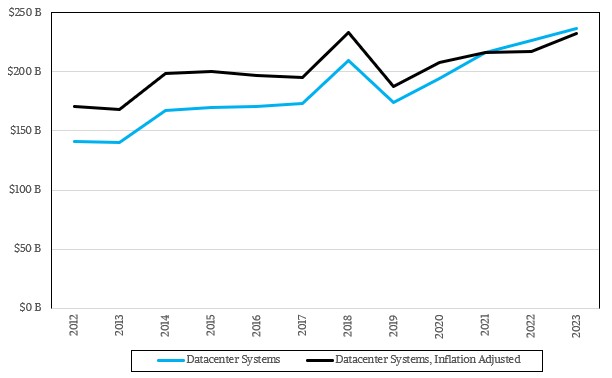

One more thing. Whenever you look at datasets that have a long time horizon, it is important to adjust them for inflation to get a sense of “actual” growth rates over time. This is particularly true with inflation being high in 2021 and expected to be high again (but not as high with monetary policy tightening across many national governments) in 2022 and 2023. So we adjusted the datacenter systems data from Gartner using the Consumer Price Index as a rough approximation of the inflation on servers, switches, and storage over the past decade and into the next two years (assuming a reasonable but still high amount of inflation).

As you can see, this has the effect of masking growth rates. If you use the raw data, then datacenter systems spending will grow by a factor of 1.68X between 2012 and 2023, inclusive. But if you adjust for inflation for the same time period, then the growth between those years in spending on datacenter gear rises only by a factor of 1.36X. This, we think, is a better indicator of actual demand than the raw revenue figures.

But make no mistake about it. This is a tremendous amount of spending increase. That is not lost on us.

Be the first to comment