COMMISSIONED Software changes like the weather, and hardware changes like the landscape; each affects the other over geologic timescales to create a new climate. And this — largely — explains why it has taken so long for open-source computing to spread its tentacles into the hardware world.

With software, all you need is a couple of techies and some space on GitHub and you can change the world with a few hundred million mouse clicks. Hardware on the other hand is capital intensive — you have to buy parts and secure manufacturing for it. While it is easy enough to open up the design specs for any piece of hardware, it is not necessarily easy to get such hardware specs adopted by a large enough group of people for it to be manufactured at scale.

However, from slow beginnings, open computing has been steadily adopted by the hyperscalers and cloud builders. And now it is beginning the trickle down to smaller organizations.

In a world where hardware costs must be curtailed and compute, network, and storage efficiency is ever more important, it is reasonable to expect that sharing hardware designs and pooling manufacturing resources — at a scale that makes economic sense but does not require hyperscale — will happen. We believe, therefore, that open computing has already brought dramatic changes to the IT sector, and that these will only increase over time.

Open Hardware Is A Social Thing

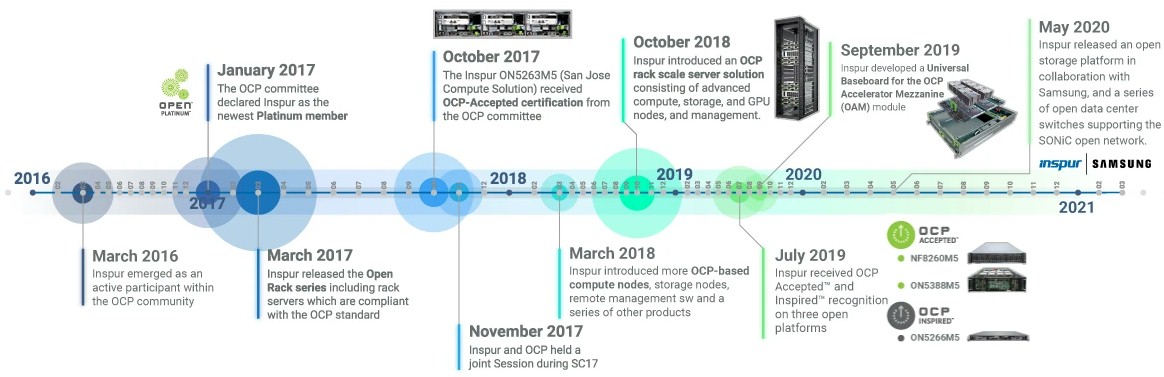

The term ‘open computing’ is often used interchangeably with the Open Compute Project, created in 2011 by Facebook in conjunction with Intel, Rackspace Hosting and Goldman Sachs However, OCP is just one of four open-source computing initiatives in the market today. Let’s see how they all got started.

More than a decade ago, Facebook growing by leaps and bounds, bought much of its server and storage equipment from Dell, and then eventually Dell and Facebook started to customize equipment for very specific workloads. By 2009, Facebook decided that the only way to improve IT efficiency was to design its own gear and the datacenters that house it. In January 2014, Microsoft joined the OCP, opening up its Open Cloud Server designs and creating a second track of hardware to complement the Open Rack designs from Facebook. Today, OCP has more than 250 members, with around 5,000 engineers working on projects and another 16,000 participants who are members of the community and who often are implementing its technology.

Six months after Facebook launched the OCP, the Open Data Center Committee, formerly known as Project Scorpio, was created by Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent to come up with shared rack scale infrastructure designs. ODCC opened up its designs in 2014 in conjunction with Intel. (Baidu and Alibaba, the two hyperscalers based in China, are members of both OCP and ODCC, and significantly buy a lot of their equipment from Inspur.)

In 2013, IBM got together with Google to form what would become the OpenPower Foundation, which sought to spur innovation in Power-based servers through open hardware designs and open systems software that runs on them. (Inspur also generates a significant portion of its server revenues, which are growing by leaps and bounds, from Power-based machinery.)

And finally, there is the Open19 Foundation, started by LinkedIn, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, and VaporIO to create a version of a standard, open rack that is more like the standard 19-inch racks that large enterprises are used to in their datacenters and less like the custom racks that have been used by Facebook, Microsoft, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent. Starting this year, and in the wake of LinkedIn being bought by Microsoft, the Linux Foundation is now hosting the Open19 effort, and the datacenter operator Equinix and server and switch vendor Cisco Systems are now on its leadership committee.

Inspur is a member of all four of these open computing projects and is among the largest suppliers of open computing equipment in the world, with about 30 percent of its systems revenue based on open computing designs. Given this, we had a chat with Alan Chang, vice president of technical operations, who prior to joining Inspur, worked at both Wistron and Quanta selling and defining their open computing-inspired rack solutions.

“It depends on how broadly you define open computing, but I would say that somewhere between 25 percent to 30 percent of the server market today could be using at least some open computing standards. It is not in the hundreds of large customers yet, but in the tens, and that is the barrier that Inspur wants to break through with open computing,” Chang tells The Next Platform. He points out that two top tier hyperscalers consumed somewhere around two million servers last year against a total market of 11.9 million machines. “With just those two companies alone, you are at 18.5 percent, which sounds like a very large number, but it is concentrated in just two players,”

‘Tens of customers” may not seem like a lot, but the server market changes at a glacial pace — and it is very hard to make big changes in hardware. For starters, customers have long-standing buying preferences, and — outside of the hyperscalers and cloud builders, many large enterprises and service providers — they are dependent on the baseboard management controllers, or BMCs, that handle the “lights out”, remote management of their server infrastructure. The BMC is a control point — just like proprietary BIOS microcode inside of servers was in days gone by.

But this is going to change, says Chang. And with that change those who adopt the system management styles of the hyperscalers and cloud builders will reap the benefits as they force a new kind of management overlay onto systems — and in particular, the open computing systems they install.

“The BIOS and the BMC are programmed in a kind of Assembly language, and only the big OEMs have the skills and the experience to write that code,” explains Chang. “Even if a company like Facebook wants to help, they don’t have the Assembly language skills. But such companies are looking for a different way to create the BIOS and the BMC, something similar to the way they create Java or Python programs, and these companies have a lot of Java and Python programmers. And this is where we see OpenBMC and Redfish all starting to evolve and come together, all based on open-source software, to replace the heart of the hardware.”

To put it bluntly, for open computing to take off, the management of individual servers has to be as good as the BMCs on OEM machinery because in a lot of cases in the enterprise, one server runs one workload, and they are not scaled out with replication or workload balancing to avoid downtime. This is what makes those BMCs so critical in the enterprise. Enterprises have a lot of pet servers running pet applications, not interchangeable massive herds of cattle and scale-out, barn-sized applications. And even large enterprises are, at best, a hybrid of these. But if enough of them gang together their scale, then they can make a virtual hyperscaler.

That, in essence, is what all of the open computing projects have been trying to do: find that next bump of scale. Amazon Web Services and Google do a lot of their own design work and get the machines built by original design manufacturers, or ODMs. Quanta, Foxconn, Wistron, and Inventec are the big ones, of course. Microsoft and Facebook design their own and then donate to OCP and go to the ODMs for manufacturing. Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent work together through ODCC and co-design with ODMs and OEMs, and increasingly rely on Inspur for design and manufacturing. And frankly, there are only a few companies in the world that can build at the scale — and at the cost — that the hyperscalers and large cloud builders need.

Trying to scale down is one issue, but so is the speed of opening up designs.

“When Facebook, for instance, has a design for a server or storage, and they open it up, they do it so late,” says Chang. “Everyone wants a jump on the latest and greatest technology, and sometimes they might like 80 percent of the design and they need to change 20 percent of it. So in the interest of time, companies who want to adopt that design have to figure out if they can take the engineering change or just suck it up and use the Facebook design. And as often happens in the IT business, if they do the engineering change and go into production, then there is a chance that something better will come out by the time they get their version to market. So what people are looking for OCP and ODDC and the other open computing projects to do is to provide guidance, and get certifications for independent software vendors like SAP, Oracle, Microsoft, and VMware quickly. All of the time gaps have to close in some way.”

The next wave of open computing adoption will come from smaller service providers — various telcos, Uber, Apple, Dropbox, and companies of this scale. Their infrastructure is getting more expensive, and they are at the place that Facebook was at a decade ago when the social network giant launched the OCP effort to try to break the 19-inch infrastructure rack and so drive up efficiencies, drive down costs, and create a new supply chain.

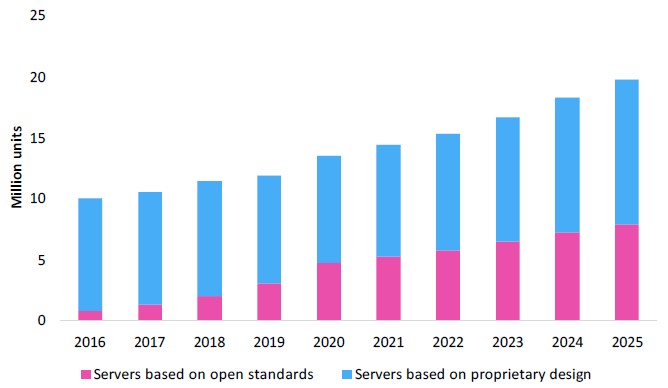

The growth in open computing has been strong and steady, thanks in large part to the heavy buying by Facebook and Microsoft, but the market is larger than that and getting larger.

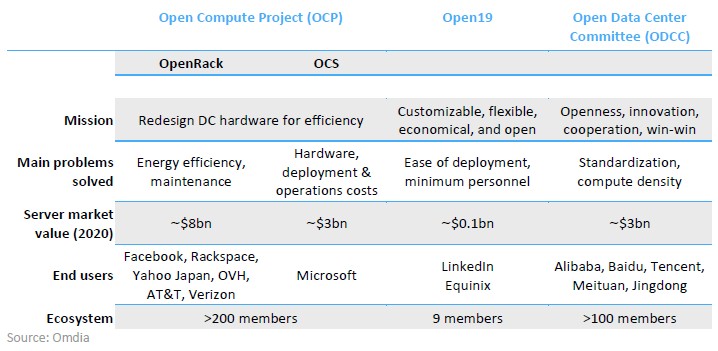

As part of the tenth-year anniversary celebration for the OCP, Inspur worked with market researcher Omdia to case the open computing market, and recently put out a report, which you can get a copy of here. Here are the interesting bits from the study. The first is a table showing the hardware spending by open computing project:

The OCP designs accounted for around $11 billion in server spending (presumably at the ODM level) in 2020, while the ODCC designs accounted for around $3 billion. Open19, being just the racks and a fledgling project by comparison, had relatively small revenues. Omdia did not talk about OpenPower iron in its study, but it might have been on the same scale a few years back and higher if Google or Inspur is doing some custom OpenPower machinery on their own. Rackspace had an OpenPower motherboard in an Open Compute chassis, for instance.

Add it all up over time, and open computing is a bigger and bigger portion of server spending, and it is reasonable to assume that some storage and networking will be based on open computing designs, following a curve much like the one below for server shipments:

Back in 2016, open computing platforms accounted for a mere seven percent of worldwide server shipments. But the projection by Omdia is for open computing platforms to account for 40 percent by 2025, and through steady growth after a step function increase in 2020. As we have always said, recessions don’t cause technology transitions, but they do accelerate them. We would not be surprised if those magenta bars get taller faster than the Omdia projection — particularly if service providers start merging and capacity needs skyrocket in a world that stays stuck in a pandemic for an extended amount of time.

Commissioned by Inspur

Be the first to comment