Whenever something is not working, you change it. Sometimes, you glue things together to create some sort of synergy and then you pull them apart to get some sort of necessary focus. The pendulum swings back, and forth, and back and forth, creating and destroying value (think building conglomerates and tearing them apart) or careers (not everyone survives the changes, by definition).

So it is with the absolutely expected reorganization with that we still call Intel’s Data Center Group when it has been called the Data Platforms Group, under general manager Navin Shenoy, for a couple of years. In the reorganization that relatively new chief executive officer and formerly not only Intel’s first chief technology officer (in 2001) and also the first general manager (in 2005) of its Digital Enterprise Group, the company’s first implementation of Data Center Group.

Gelsinger, who learned from Intel’s own founders, is no slouch – he was one of the designers of the 80386 processor and the architect of the 80486 processor that got Intel on the path to the datacenter way back in 1985 – and is probably still the best person to run whatever Intel might want to call Data Center Group. Particularly after running storage giant EMC and running server virtualization juggernaut VMware since leaving Intel in 2009. But Gelsinger can’t run Data Center Group because he is CEO of all Intel. But he can do the next best thing, and that is to get rid of Data Center Group and create new “groups” that perform its functions, which are really divisions, and have the heads of those groups report directly to him. And that is precisely what he has done. And the reorganization that will be effective July 6 shows how Intel intends to organize itself to take on the many competitive threats it has in the datacenter these days.

First of all, when you have the lion’s share of datacenter compute, everyone is gunning for you. And so Gelsinger wants to break the threat to its hegemony in compute down into defensible territories. At the same time, some parts of Intel naturally can be glued together to create a larger set of groups that, in theory at least, can produce some synergies as well as a more coherent story for Intel to tell to partners and customers.

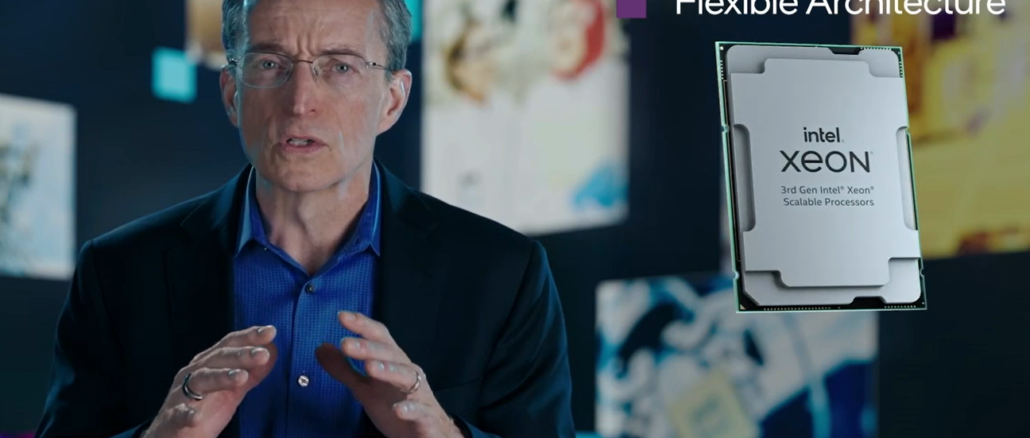

To that end, the Data Platforms Group – again, what most people still think of as Data Center Group – will be split into two pieces. Sandra Rivera is the general manager of the new Datacenter and AI Group, which will include the Xeon processor lines as well as the Arria, Stratix, and Agilex FPGAs. Rivera, who used to run Intel’s Network Platforms Group (the part of Intel dealing mostly with its expansion into the telco and service provider arena), will also be spearheading Intel’s AI strategy, which presumably means also taking control of the Habana Gaudi and Goya AI accelerators as well as the Loihi neuromorphic processors. (Intel was not explicitly about this part.) In her most immediate prior role, Rivera was Intel’s chief people officer, but make no mistake. Gelsinger clearly wants people with technical chops running Intel’s groups, and Rivera has an electrical engineering degree from Penn State University. (Go Lions!)

With AMD on the rise and Arm server chips coming from Ampere Computing as well as the cloud builders and hyperscalers for their private use, there has never been a tougher time to run the core datacenter processing business at Intel. And there has also never been a better environment in which to shape new executives for future leadership. Gelsinger knows that intimately because that is what Andy Grove saw in him back in the 1980s and 1990s as Gelsinger rose up through the Intel ranks, and taught him how to run Intel. Rivera did sales at Dialogic, a telecom equipment supplier based in AT&T’s old stomping grounds in New Jersey and then was general manager of the computer telephony division at Catalyst Telecom, a value added distributed in the telco space. Interestingly, Intel bought Dialogic for $780 million at the height of the dot-com boom, but that was a few years after Rivera left for Catalyst. The point is, Rivera has a different set of experiences from many other Intel execs as well as more than two decades at Intel.

The other half of the former Data Platforms Group is now the Network and Edge Group, and Gelsinger has managed to convince Nick McKeown, one of the founders of Barefoot Networks (which Intel acquired for its programmable Ethernet switching business two years ago), to take a full-time gig at the chip maker and become general manager for the Network and Edge Group. (Which Intel is mysteriously abbreviating NEX, which we will never do here at The Next Platform.) McKeown has been a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at Stanford University since 1995 and was an innovator in software-defined networking, culminating with being a co-founder of Nicira (which was acquired by VMware in 2012 for $1.26 billion). McKeown spent a little time thinking and in 2013 founded Barefoot Networks to leverage the P4 programming language to create programmable switch ASICs.

Intel is building out and building up its Xe GPU business to take on both Nvidia and AMD, and to that end it is creating a new Accelerated Computing Systems and Graphics Group (abbreviated AXG by Intel for some reason) under Raja Koduri, who has been Intel’s chief architect and general manager of its Cores & Visual Computing & Edge Computing solutions since 2017. (This title did not make much sense, as we suspect much of Koduri’s job did not either. But Intel has been trying to put out engineering and manufacturing fires for years.) Koduri cut his teeth at graphics chip maker S3 in the 1990s and joined AMD as its chief technology officer for its Graphics Products Group in 2001. He then went to Apple for four years, from 2009 through 2013, to run its graphics chip development, and then came back to AMD to work on AMD Radeon GPUs in the wake of the acquisition of ATI Technologies.

Finally – and this is going to fuel the speculation even more that Intel wants to buy VMware – Gelsinger has created a new Software and Advanced Technology Group, and he has brought Greg Lavender, formerly chief technology officer at VMware, into Intel to do it. Lavender has also been appointed the chief technology officer over all of Intel, so he is doing double duty – just like Gelsinger used to do at Intel many years ago. Lavender was in charge of the Web infrastructure software stack at Sun Microsystems after the company he worked at, Innosoft, was acquired by Sun in March 2000. Lavender was put in charge of the Solaris operating system in 2008, when Solaris was opened up and made available on X86 iron, and stayed on until Oracle acquired Sun in 2010. Lavender has been a professor of computer science at the University of Texas since 1994. As part of that CTO job, by the way, Lavender will be in charge of Intel Labs as well as driving Intel’s entire software agenda – and it will be interesting to see what this might be.

These are the four pillars of Intel’s of Intel’s datacenter strategy, and the people all report up directly to Gelsinger and the strategy they will implement is no doubt coming from above. Three out of the four are hardcore, seasoned techies who have been at this IT game a long time; one is getting a chance to become a seasoned techie. Which is refreshing to see, of course. And frankly, the core datacenter compute business is the easiest of the challenges that Intel is facing in the datacenter. It has been much less successful in discrete graphics, GPU accelerated computing, switching, and specialized AI and neuromorphic chips. We can debate how well Intel has done with network interfaces and SmartNICs, and what its DPU strategy is for the future. And it has had mixed results in the traditional high performance computing segment, too.

Presumably, Intel’s financials will be cast to reflect these new groups, and we can get some insight into how they do going forward and perhaps back four quarters.

Do still think Intel wants to buy VMWARE? Intel has a great relationship with Dell? What does VMWARE have that Intel needs?