There are many things that are ironic in the IT business. Too many to count, some days. And maybe it is just because many of us are attending the virtual Open Compute Summit driven in large part by Facebook and Microsoft (still). But it looks like momentum is building for the SONiC network operating system, launched four years ago at the Open Compute Summit by Microsoft and open sourced under the auspices of what had been, until that moment, an organization largely devoted to open source hardware. Not software.

The world is a funny place, indeed. Incumbent switch makers created the most recent iterations of their network operating systems from Unix kernels and, later, Linux kernels. IOS from Cisco Systems dates back more than three decades and is its own beast, but its follow-on, NX-OS for the Nexus line of switches, is based on Linux, just like Arista Network’s EOS network operating system is. JunOS from Juniper Networks is based on FreeBSD, but has its own hooks to Linux. And of course, Cumulus Networks, which was just acquired by Nvidia in the wake of its $6.9 billion acquisition of switch, NIC, and chip maker Mellanox Technologies at the end of April, is based on Linux and so are the Mellanox MLNX-OS and Onyx switch operating systems. The hyperscalers and large cloud builders have created their own NOSes as well, as far as we know all based on Linux, and finally there is Arrcus, which has created a homegrown routing and switch operating system called ArcOS from scratch with its own kernel.

Microsoft created SONiC not because it wanted to embrace Linux on its switches, but because it had no choice. There was no real benefit to trimming down a Windows Server kernel to be the heart of a switch operating system and there was every reason to use the substantial Linux expertise in the world to make a NOS that could run all of its Azure cloud infrastructure connectivity. And that, according to Dave Maltz, distinguished engineer at Microsoft’s Azure Networking division, is what has finally happened. At the virtual Open Compute Summit today, Maltz said that the Azure Networking service is now running SONiC top to bottom, and significantly it can run not just top of rack switches, but modular rack switches that are used to create a giant logical switch out of line cards that are essentially the same as a top of racker but with a backplane lashing them all together.

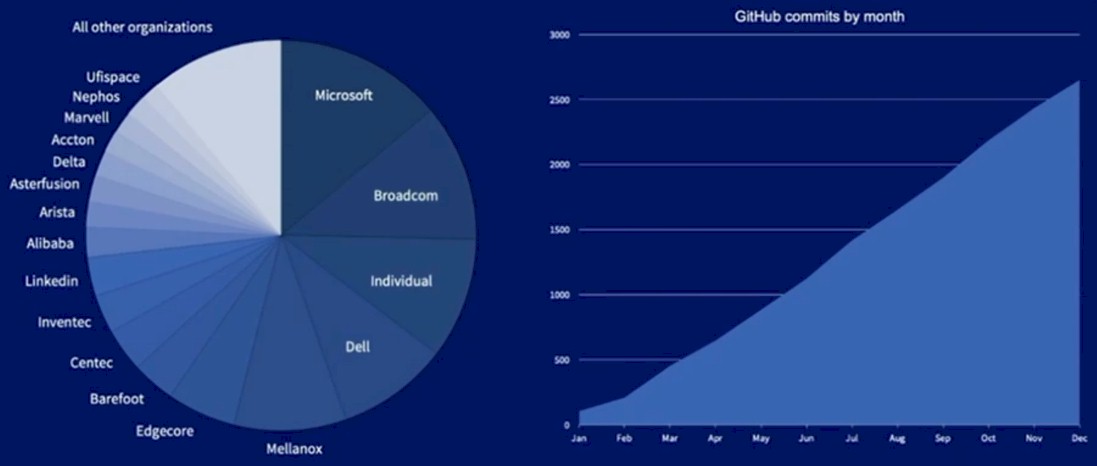

According to Maltz, more than ten of the hyperscalers and cloud builders and a number of large enterprises have all adopted SONiC as their switch operating system, with Microsoft and Alibaba being the two biggies that are on the record.

When Microsoft launched SONiC and its companion Switch Abstraction Interface (SAI) back in 2016, it started out with modest Layer 2 and Layer 3 switching functions running in containers atop a Linux kernel with a Redis database for telemetry. The software ran on several ASICs, including Broadcom’s Trident 2, Mellanox’s Spectrum, Cavium’s XPliant (now part of Marvell), and Centec Networks’ GoldenGate; these were used predominantly for 40 Gb/sec switches, and there were a handful of options. In the following year, Broadcom’s Tomahawk and Tomahawk 2 ASICs were added as well as Marvell’s Prestera and Barefoot Networks’ Tofino, and these additions were for 100 Gb/sec switches and there were around 16 different platforms available. RDMA and QoS features were added to the SONiC stack as was management via Swarm (the old Docker tool). In 2018, there was another big jump with SONiC as virtualization was added to container support and warm reboot (in under 1 second) was added along with streaming telemetry and a new config database. Arm compute support was added, and the platform list grew to 31 unique machines, including those based on the Taurus chip from Nephos, the Helix 4, Trident 2, and Tomahawk 3 chips from Broadcom, and the Lacrosse chip from Cisco (used in the high-end Nexus 9000 switches). Last year, support for SONiC on the Broadcom Jericho and Jericho 2 deep buffer switch ASICs was added, as was support for Innovium’s Teralynx 7, Marvell’s Falcon, and Mellanox’s Spectrum 2 ASICs. The base of platforms grew to 69 different machines, and significantly, Microsoft worked with the SONiC community to add in support for modular switches, which Maltz calls chassis switches. Cisco has added its Silicon One merchant router chip to this list earlier this year, and there are no doubt others we have not heard about as yet.

This is an incredible ramp when you consider that Cumulus Networks only supported Broadcom and Mellanox ASICs and Arrcus is focusing on the Broadcom families at this point. Granted, the Broadcom ASICs get you something on the order of 65 percent of the datacenter switch market share at this point, so you have to be making money – or be a highly motivated open source collective – to add all of these other ASICs to the hardware abstraction list.

Of course, that was precisely the point when Microsoft created SONiC and SAI and then turned around and open sourced it and donated it to the Open Compute Project community. And today, according to Maltz, there are 3.84 million ports in the worldwide base of Ethernet ports that are being driven by SONiC. That’s many billions of dollars worth of switches, any way you want to cut it.

And now the telcos, service providers, and enterprises are probably going to follow suit. Maltz says that eBay is evaluating the use of SONiC in its networks, and Comcast is looking at using SONiC-based gear at the datacenter core. French Internet advertising broker Criteo is going to be using SONiC switches exclusively in 2020 and beyond, and retailer Target (which has had famous network security issues in the past that hammered its stock) is going to adapt SONiC network gear as well.

It is not surprising, then, that someone is stepping up to offer a supported SONiC distribution. And in fact, Dell Technologies and Apstra both announced formal SONiC distributions and enterprise support engagements today at the virtual Open Compute event.

In January 2016, only months before Microsoft dropped the SONiC bomb, Dell open sourced its own FTOS OS10 network operating system, which it got by virtue of its acquisition of switch maker Force10 Networks in the summer of 2011. Dell kept its hand in the OpenSwitch (OPX) project it spawned; it also participated in the SONiC community started by Microsoft and was an early adopter of Cumulus Linux on its switch gear.

“We had our feet in two different puddles,” Drew Schulke, vice president of networking at Dell Technologies, tells The Next Platform. “What it really comes down to, as is the case with a great many open source projects, is that you look and see who has the gravitational pull, who gets the customer adoption, who gets the ecosystem support. And our call about a year ago was that SONiC was winning that battle and was going to be declared the victor. We didn’t drop OpenSwitch like a bad habit, but spun it into the Linux Foundation and made it part of the broader Open Networking Linux project. But our focus going forward is very much going to be on the SONiC side.”

One of the selling points of SONiC, says Schulke, is that it is container friendly from the get-go, which means that companies can add their own secret sauce to it without mucking about in the base NOS kernel and having to upstream code into the Linux kernel. (Imagine that.) And based on its Azure heritage, it is very good at Layer 3 underlays and Layer 3 fabrics using an EVPN overlay. But Dell will be working on adding more Layer 2 functionality in the coming months as well as Multicast, IGMP snooping, Uplink Failure Detection, and eventually the Open Shortest Path First routing protocol. These additions to SONiC will be open sourced by Dell, incidentally. The Enterprise SONiC Distribution by Dell Technologies is the formal name of the Dell rollup of SONiC that is sanctioned by Microsoft, and it will be generally available in the third quarter with those additional Layer 2 features with support contracts of one, three, or five years. Pricing will scale by the bandwidth of the switch, with it costing in the range of a couple of thousand dollars per switch per year.

The rest of the SONiC community has its own ideas about what to do in the future.

“We are working on deploying SONiC at the edge for 5G deployments to places where we need to put computing right up next to the wireless edge so it can be close to the consumers and producers of that information,” Maltz explained in his keynote address.

“SONiC will be there offering a trusted base platform that can be used to bootstrap securely all the other infrastructure necessary at the edge. We’re doing SONiC-based load balancers rather than having a proprietary load balancer that has to be a specialized box in your network architecture.

“Running SONiC on top of existing network ASICs you probably already have can to offer Layer 4 load balancing, again bringing load balancers into the same network management framework you already have for the rest of your network devices. We have ideas about managing SONiC via Kubernetes, which is a great platform for deploying cloud services, and managing SONiC through Kubernetes means you can leverage the abilities already present in your software team, enabling you to deploy new containers to those switches so you can innovate faster and more safely and using the frameworks that your engineers are already used to. We’re looking at how we can take machine learning and apply that to Sonic into the management of networks. One of the hardest problems every network operator has to deal with determining whether their network is healthy or not. And if it’s not, what’s the problem?

“Leveraging the ability of SONiC to expose new telemetry from the switches to do flexible computation on those switches themselves and send that data back to larger networks and systems which can then do machine learning and analysis. Other communities working to build better network management solutions that will make it easier to have a healthy and reliable network. We’re also taking Sonic, the other team, and running it open to some of the biggest switches in the network. We’re taking it down onto the individual servers using Sonic as a management platform for SmartNICs, providing flexible ways of offloading network transformation from the server to the SmartNIC, but yet still managing that SmartNIC as if it was a network switch – something that many of us are. Companies already have software automation systems that can handle.

“And of course, one of the challenges we’ve talked about in the past was making good on now is taking Sonic out to the very largest switches is in the network –those that run the wide area network – so SONiC can truly be the one network operating system from backbone switches down through our datacenters to the 5G edge and all the way onto our servers as part of that SmartNIC solution.”

That sounds like a pretty comprehensive strategy to us. The wonder is that Microsoft doesn’t roll up support for its own SONiC distribution, or IBM’s Red Hat division doesn’t. Or both, for that matter.

Be the first to comment