Nvidia’s DGX platforms are powerhouses for training neural networks, offering up to 2 petaflops of peak machine learning performance. But the GPU-laden systems come with an eye-watering power budget – up to 12 kilowatts in the case of the top-of-the-line DGX-2H. That kind of energy density makes it a poor fit for conventional datacenters. To get around that, Nvidia has come up with DGX-Ready, a program that puts its AI server hardware into colocation centers.

One of Nvidia’s newest colo partners is Verne Global, a cloud and colocation provider that caters to the high performance computing market. Its Icelandic datacenters take advantage of the low local power costs (thanks to an abundance of geothermal energy plants), as well as a naturally cool climate, to reduce the cost of running high-powered clusters.

The majority of Verne Global’s clients are in Western Europe, where energy prices are high and upgrading datacenters to bring in additional power is often not practical. Prime customers including financial service firms, engineering companies, and government labs. According to Bob Fletcher, Verne Global’s vice president strategy, the big advantage of coming to Iceland is that the computational costs are about a third of that of a regular datacenter in Europe. And since Icelandic energy isn’t based on fossil fuels, companies looking to reduce their carbon footprint are provided an additional incentive.

In Munich, for example, electricity costs between 22 cents and 26 cents per kilowatt-hour, while in Iceland, it is around 5 cents per kWh. And since Iceland’s northern latitude means the air is cold year round, there is no need to run expensive refrigeration units for the facilities. Savings can add up quickly, especially for large deployments. For example, if you have 100 racks or equipment, Fletcher says you can save the cost of the hardware in about 18 months of operation.

A number of Verne Global’s customers are using the company’s datacenters for AI work like machine vision, natural language processing (NLP) and drug discovery research. Since the training datasets can get rather large – about 10 TB for one of its NLP customers – the site’s 100 Gb/sec connectivity to the outside world is used to good effect for uploading.

All of which made Verne Global a good pick the DGX-Ready program, becoming one of only four colocation partners in Europe. Nvidia is rather particular about who it chooses for this program, according to Fletcher, since the centers have to offer exceptional cooling and power capabilities for the DGX hardware. The program ensures the facilities can handle 30 kilowatts per rack, with the ability to reach 50 kilowatts. The centers also must adhere to strict security requirements.

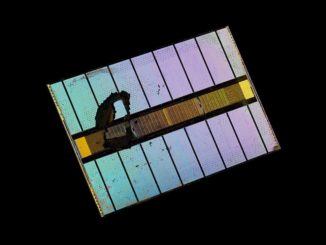

The latest DGX-2 hardware, which is outfitted with 16 V100 GPUs, is certainly not your typical datacenter server. The standard configuration draws 10 kilowatts, while the top-end DGX-2H that is outfitted with speedier V100 GPUs and Xeon CPUs uses 12 kilowatts. If you hook a couple of them together along with some networking and external storage, you’re easily looking at a rack at 30 kilowatts. That’s six times the 5 kilowatts per rack average for typical datacenter gear. “Most corporate datacenters are not designed to deliver that kind of power to a rack or to deal with the sort of heat that that generates,” Fletcher told us.

In datacenters like Verne Global’s that are doing a mix of machine learning and other work, Fletcher says it’s easy to tell where the model training is taking place just from the hum of the server fans. “You’ll go into one area and there’ll be modest fan noise,” he says. “Then you go into an area doing neural net training and it sounds like a jet engine.”

That makes arranging AI hardware within a facility somewhat challenging, since you have to make sure that the hot air being blown from the rear of one system is not being blown into the rear of another system that’s also trying to shed its heat load. You’re better off placing less power-hungry networking and storage gear opposite the GPU-dense hardware. This is especially important because systems like the DGX-2 will monitor their temperature and if it determines it’s exceeding its thermal threshold, it throttles down the GPU speeds or even takes some of them offline. Which sort of defeats the purpose of providing so much computational density.

Although the DGX-2 systems can be used for traditional HPC work, Fletcher thinks most, if not all, of them will be used for machine learning workloads, primarily for training neural networks. Although, the DGX boxes have the capability to do inference as well, latency can become an issue due to its remote location.

That doesn’t rule out inference work entirely, however. Fletch says it’s only a 40 millisecond round-trip from Iceland to London and a 50 millisecond round-trip to Munich. That fine for many inference applications involving web page messaging. But for more latency-sensitive application like programmatic trading, online gaming, or ad serving, the response times has to be even faster. Nevertheless, Fletcher believes they will see more users doing tightly coupled training and inference work, where the model is being updated in real time.

Verne Global, which we profiled here when it first debuted its hpcDIRECT service, currently has two datacenters on its 42 acre site, together drawing about 20 megawatts of power. Since the company’s power provider can deliver 100 megawatts, Verne Global has a lot of headroom for future growth. Fletcher says over the next year Verne Global expects to completely fill its existing two centers and expand to a third one.

Not all of Verne Global’s customers are using machine learning or even GPU hardware, but Fletcher says the company is anticipating fast growth in the AI marketplace over the next few years. That, he believes, will necessitate more power-intense systems like the DGX-2. And since its datacenters offer cheap energy and nearly free cooling, that should give Verne Global a natural advantage as companies build out their AI infrastructure.

Be the first to comment