There has never been a better time to wait to buy processors for servers, and in the second quarter of this year, based on the financial results that Intel has turned in, many companies did just that.

It looks like a lot of the extra capacity that companies bought during the “Skylake” generation of Xeons was intended to tide them over as we all await the on-time and impending arrival of the “Rome” Epyc processors from AMD and the reactionary and much-delayed arrival of Intel’s “Ice Lake” Xeon processors. And the pressure will be even more intense after AMD has Rome chips in the field. Up until now, the server market has expanded fast enough that AMD could gain a few points of share while at the same time allowing Intel’s numbers to grow – albeit not as fast as they might have without AMD in the market. But soon, AMD is going to enter the field with its second generation of Epyc chips, and we think people will stop kicking the tires as they did with the first generation “Naples” chips and actually buy the car.

This is a return to normalcy, and it is as healthy for Intel as it is for AMD and customers. This competition between AMD and Intel is doing no favors for IBM’s Power chips or the few server chips available from the Arm collective, however. With a credible number two supplier of X86 chips, the other options are inherently less appealing despite their technical superiority on many fronts. Changing an instruction set is a big deal, and Windows Server for one is landlocked onto X86 unless and until Microsoft really puts some weight behind Arm chips above and beyond its own internal use here and there on the Azure public cloud.

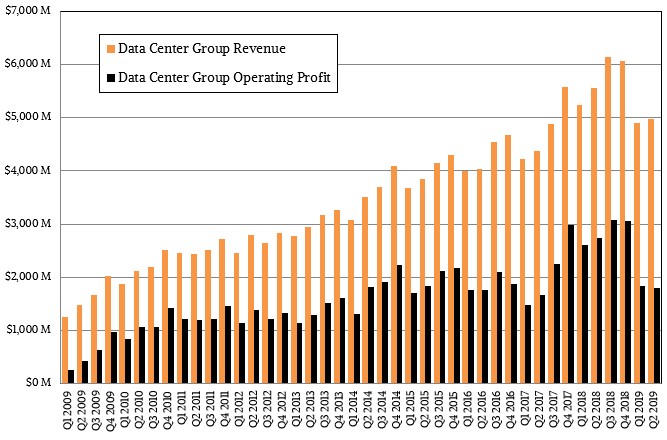

This was not a great quarter by recent standards for Intel’s Data Center Group, but the company is still larger than many might have expected in this arena a decade ago and is still wildly profitable. We think those profits will come under pressure as Intel ramps its 10 nanometer processes and starts putting its 7 nanometer techniques into the fabs, and there are already indications of this. The pricing pressure from AMD will also cut into Intel’s sales volumes and profits, so there is a pincher effect that is looming. In fact, in some hyperscale and cloud builder accounts, they have long since already made their Rome Epyc purchases, so whatever is going to happen in the enterprise space over the next few quarters has already happened there. (Yet another way the hyperscalers and cloud builders predict the future.) Intel might be buying Barefoot Networks as much to have a value add to provide to Xeon customers as it is to get its hands on the “Tofino” programmable switch ASICs and the P4 network programming language.

In the quarter ended in June, Intel booked $16.51 billion in sales, down 2.7 percent; operating income fell by 12.4 percent to $4.62 billion and net income fell by 16.5 percent to $4.18 billion. Don’t blame the PC side of the Intel house for this. In the quarter, the Client Computing Group had $8.84 billion in sales, up 1.3 percent, and operating income rose by 15.6 percent to $3.74 billion. For the past several quarters, Intel has had shortages of its Core processors for PCs and has been concentrating on higher-end chips and sacrificing low-end market share to AMD. This is a tactic we expect Intel to repeat in the server space as AMD gets more traction and as we expect for chips based on the new manufacturing processes (a mix of 14 nanometer and 7 nanometer for AMD, and 10 nanometer for Intel) to be somewhat scarce at the beginning of their yield curves. Intel will maximize revenue and profit and yield some share to AMD. This is the smart thing to do, under the circumstances.

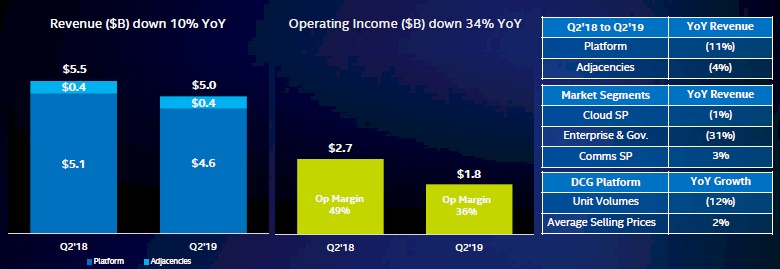

The June quarter was a tough one for Intel’s data centric businesses in general and its Data Center Group in particular. The Data Center Group had a little more revenue and a little less profit than it turned in during the first quarter of 2019. The platform part of the business, including Xeon processors, server chipsets, motherboards, and systems that it sells to key customers, had $4.55 billion in sales, down 10.7 percent, while adjacencies (which includes things like SmartNICs and Omni-Path networking) had sales of $430 million, down a more modest 4.2 percent.

Add it all up, and Data Center Group’s total revenues were $4.98 billion, down 10.2 percent; operating profits for the group fell by a much more dramatic 34.2 percent to $1.8 billion. That is only 36.1 percent of revenue, and a far cry from the 50 percent or so that Intel has averaged for Data Center Group for the past decade. George Davis, chief financial officer at Intel, said on a conference call with Wall Street analysts last week that Data Center Group’s revenues were slightly ahead of expectations, with platform average selling prices up 2 percent year on year. Xeon processor ASPs were up “double digits” as customers keep buying up in the stack, but unit ships were off 12 percent and that brought revenues down significantly, obviously.

The big hit came in the cloud service provider space – what we at The Next Platform call the hyperscalers and the cloud builders. The cloud service providers have fueled Intel’s growth in the past decade, but in this quarter, sales across this upper echelon of customers were down 1 percent, which Intel chief executive officer Bob Swan attributed to these customers needing to “digest” the capacity they have acquired in recent quarters. Communication service providers – who are comprised of the big telcos, cable companies, and other services companies that sell capacity in one form or another – booked a 3 percent revenue bump.

Enterprises and government institutions, who used to be the backbone of the Intel Xeon business, have been diminishing their spending for the past decade as they move some jobs to the cloud, but even the 31 percent drop that enterprise and government spending at Data Center Group seems a bit much and is reminiscent of the dropoff we saw during the Great Recession. There is no recession as far as we know, just a transition of many workloads to the public cloud and an effort to run infrastructure more efficiently and to get rid of the need for so much spare capacity thanks to the cloud. Swan said that enterprise and government spending in China was particularly weak, which doesn’t surprise us, but we wonder what they might be buying instead. (Hmmm….)

The inevitable crash in flash pricing, which has help prop up server ASPs and Intel’s memory business for the past several years, has come, and sales in the Non-Volatile Storage Group, part of what Intel calls its “data centric business segments,” dropped by 12.9 percent to $940 million, and operating losses more than quadrupled to $284 million.

The Programmable Solutions Group, which is where the Altera FPGAs live, saw a sales decline of 5.4 percent to $489 million, and operating profits were down by 48.5 percent to $52 million. We are not sure if this is because of increasing competition with Xilinx, which is ramping sales of its “Everest” FPGAs, but we suspect that this is the case.

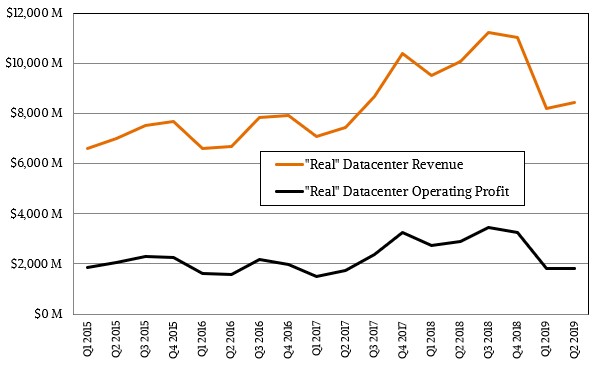

If you try to figure out what Intel’s “real” datacenter sales are, it paints a slightly different picture from the presentation that Wall Street gets. A portion of sales from the IoT Group, Programmable Solutions Group, and Non-Volatile Memory Solutions Group are truly aimed at the datacenter, not consumer products. We take a stab at this each quarter, and here is what the trend looks like:

This chart assumes that half of the IoT sales and 75 percent of the flash and FPGA sales are aimed at the datacenter and its edge, and if you add that to Data Center Group proper, then Intel’s “real” datacenter business had $6.65 billion in sales, down 7.5 percent, with operating profits of $1.8 billion, down 37.6 percent and only comprising 27.1 percent of revenue. If we are right, then Intel’s true datacenter business is less profitable than the formal Data Center Group numbers. Which explains why Intel dices and slices the numbers the way it does.

It was a tough first half with a very tough set of compares given how hyperscalers and cloud builders were spending like drunken sailors in the first half of 2018, but Intel is sanguine about the second half as “Cascade Lake” sales ramp and it prepares to get its “Cooper Lake” follow-on and “Ice Lake” kicker into the field in 2020.

“Although we have seen a weaker first half in our datacenter business, we expect a better second half as demand from cloud and comms service providers improves and our second generation Xeon SP continues to ramp,” Swan said on the call. Swan added that Intel did not expect for spending across enterprise and government sector “won’t get dramatically better,” and Intel is counting on a rebound among the hyperscalers and cloud builders in the second half to prop up Data Center Group. If AMD takes more share, as we expect it will do with Rome Epycs, then the buildout is going to have to be record breaking if Intel will rise, even against the relatively easy compares to Q3 and Q4 of 2018.

We shall see. Whatever will happen has already largely happened – we just don’t know it yet. And no matter what, real competition always makes Intel fight harder for the money, with both technology and pricing. This is a good thing.

Typo:

“Intel has had shortages of its Core processors for PCs and has been concentrating on higher-end chips and sacrificing low-end market share to Intel (correction:AMD).”

Ice Lake might be contemporary with AMD’s Rome CPUs, but Ice Lake is certainly not “reactionary”, especially given the public history of Ice Lake, and given how long it takes to design and test a CPU. If you want to paint Intel as being reactionary (to AMD), then point at the Platinum 9xxx SKUs (“we can put multiple dies on a chip too!”), or the W 3xxx / Gold 6xxxU SKUs (“we can discount single-socket configs too!”).

Hi Timothy- we met a few years ago when I was at ScaleMP at a deli for dinner in NYC.

I was reading the article – https://www.nextplatform.com/2019/07/29/real-competition-puts-intel-data-center-group-in-the-pinchers/

and the following sentence did not make sense wrt the final word. I think you meant AMD. I hope all is well with you.

For the past several quarters, Intel has had shortages of its Core processors for PCs and has been concentrating on higher-end chips and sacrificing low-end market share to Intel.

Thanks for the catch. Correct.