The company best known for its Windows operating systems and related client and server software but also one of the big five cloud players on Earth is getting into the edge computing business with a set of Azure offerings designed to put compute resources a lot closer to the customer’s data.

At the heart of these new offerings is the Data Box Edge, an edge server that can provide local processing, along with access to the Azure cloud. It has been available for early customers as a preview product since September 2018, but as of this week is generally available.

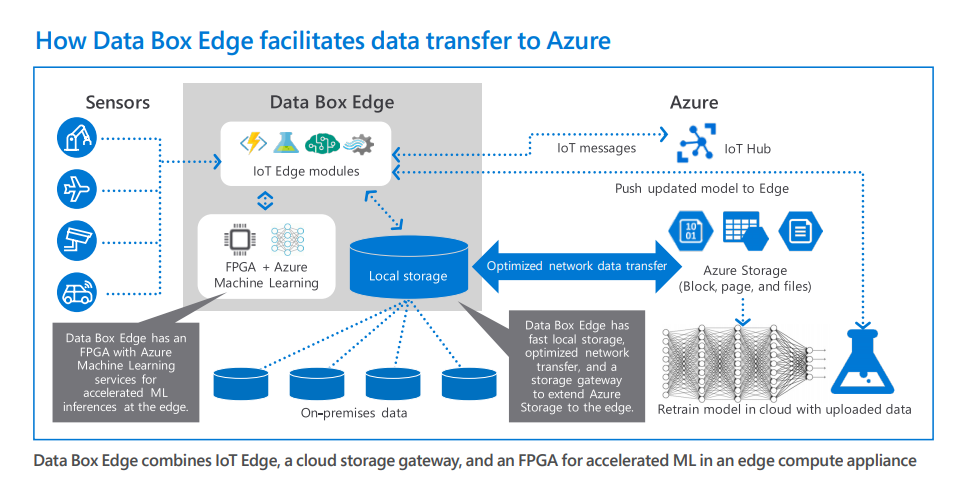

The new edge server gives customers a way to do more of their number crunching on-premise, making it easier to manage issues like latency, security, and compliance, as well as to reduce costs associated with transferring large swathes of data to a cloud datacenter. The general idea is to do as much on-site pre-processing of data as possible (which can include some amount of machine learning) and then ship the results off to an Azure cloud datacenter for further processing, long-term storage, or what have you.

Potentially, that can save a lot of data transfer time and effort, especially when you’re talking about things like real-time video, much of which is often redundant. For those types of applications, cloud storage and data transfer costs can be reduced substantially if all the uninteresting imagery can be filtered at the source.

The Data Box Edge is meant to be installed at the customer site, which can be either in a datacenter facility or in a more typical edge environment, like inside a retail outlet or on a factory floor. The 1U rack-mountable appliance is equipped with two 10-core Intel Xeon CPUs, 128 GB of memory, a 12 TB NVM-Express SSD, and four 25 Gb/sec Ethernet network ports.

An Intel Arria 10 FPGA is also included in the appliance for its machine learning smarts. An FPGA might seem like an exotic way to offer machine learning to edge customers, but in this case, Microsoft is repurposing its Project Brainwave technology, the architecture upon which the company has built a set of tools to supply much of Azure’s machine learning capability. And even though Brainwave originally debuted in the Microsoft datacenters, from the start, it was also devised as a way to bring machine learning to customer sites. In these edge environments, the idea is to perform some amount of training with on-site data, and then upload it (or some portion of it) to the Azure cloud to refine the model.

Customers don’t pay for system itself. Instead, the box is treated like an Azure utility. For a single unit, Microsoft is charging a monthly subscription fee of $336 (for 10 TB), not including shipping and any relevant customs fees.

The appliance also includes the Data Box Gateway, a piece of software that was also announced this week. It provides a network gateway to Azure cloud storage, offering seamless uploads. For customers who opt not to deploy the Data Box Edge, the gateway can be installed as a virtual appliance on other hardware. It costs $125 per month, not including the standard storage charges on Azure.

Offline storage transfers are also possible with another set of Data Box products that are meant to be physically shipped to the customer and then back to Azure once they’re filled with data. Three different flavors are offered: the standard Data Box (100 TB), the Data Box Disk (8 TB to 40 TB), and Data Box Heavy (1 PB). The one-petabyte box is still in preview mode, but the other two are available for order today. Note that usable capacities are about 20 percent lower than the numbers listed here.

Since pre-announcing the appliance last September, a handful of early customers went public with their experiences.

One of them is Kroger (more specifically, its Sunrise Technology division), which used the Data Box Edge in a retail setting to provide in-store product recommendations and guided shopping for their customers. It also used real-time video analytics to identify out-of-stock items so that employees could re-order or re-stock them.

Another early customer, Esri, a mapping and location analytics specialist, used it to develop a system for disaster responses in cases where network access is unavailable. Using imagery captured from air or ground cameras, the Data Box Edge was able to provide updated maps that could be used by disaster workers to coordinate responses.

One of the first Data Box Edge customers was Cree, a provider of power and radio frequency semiconductors, which used the appliance to archive millions of quality-control photos from their manufacturing process. In the future, they plan to develop a model that identifies defective parts in real-time.

Microsoft’s foray into edge computing is not without its risks. If customers get too comfortable processing their data locally, they may end up abandoning their reliance on cloud resources entirely, or at least substantially. To make this work, Microsoft has to offer these services at price points that doesn’t cannibalize its more expansive cloud offerings, but not so costly as to drive customers to cut the cord and buy their own hardware. Of course, that’s a prospect every cloud provider already faces.

Microsoft needs an architecture like Google for gaming.

Google has 7500+ POPs with fiber back to Google data centers.