Architectural transitions for layers in the IT stack at hyperscalers can happen in a matter of years, and cloud builders and HPC centers can move at almost the same speed. But for the vast number of enterprises, it takes a long time to change their stacks, in part because they are more risk averse and in part because they have more – and more diverse – applications to support to run their businesses.

This, we think, is one of the reasons why the transition from bare metal to cloudy infrastructure is taking so long in the enterprise, even as it has long since taken over at the hyperscalers and cloud builders and is making significant headway – mostly due to the advent of containerized environments that are significantly less heavy than clusters that are virtualized with full-on hypervisors – in the HPC realm.

The slow but steady transition to cloudy infrastructure is evident in the latest statistics coming out of IDC, and for fun we went back into the archive of publicly available data from IDC to supplement some of the trend data that was included with the latest Cloud IT Infrastructure Tracker service from the market researcher.

In this tracker, IDC figures out worldwide spending on servers, enterprise storage, and Ethernet switching across the whole IT sector, and does two important things with this data. The first is that it eliminates double or sometimes triple counting that would happen if you just added together the information available from its quarterly trackers for servers, storage, and switching in the datacenters of the world. The line between servers and storage and networking is sometimes fuzzy with the rise of software-defined storage, which just means running something like Ceph, Gluster, GPFS, Lustre, or homegrown object stores or file systems on top of clustered servers that happen to have a lot of bays for disk storage. The server chunk of such setups gets counted in the revenue and shipments for the IDC server tracker, these clustered storage setups get counted in the storage tracker, and the Ethernet switches get counted in the networking tracker, and the overlap is significant enough to give the wrong impression.

In the latest cloudy infrastructure tracker, IDC does not provide a breakdown of these software-defined systems distinct from bare metal servers or switches sold by themselves or self-contained storage appliances that are still popular in the enterprise, but it does separate cloudy infrastructure sales into three different revenue streams.

The first stream includes revenues in the public cloud, which includes the hyperscalers that provide services to consumers and companies atop their infrastructure as well as cloud builders and other kinds of service providers that sell infrastructure on a utility basis so organizations can run their own applications atop it.

The second stream is the cloud-enabled infrastructure that enterprises buy for their internal consumption, and the third stream is traditional infrastructure that is not virtualized or containerized and that tends to run standalone applications and databases or does some basic back-end function such as print, file, Web, and various kinds of application serving and, in many cases, bare metal applications such as scale-out data analytics or HPC simulation and modeling.

IT vendors have not reported their financial results for the fourth quarter of 2018 as yet, so the latest figures on cloud IT infrastructure sales that IDC has available are for the third quarter; it will take the company some time to gather up information from the hundreds of major vendors and their channel suppliers to estimate revenues in these areas for the fourth quarter. (The revenues tracked by IDC for this service include factory revenues from vendors plus channel markup for those who sell through the channel.) IDC did provide some projections for 2018 as well as out to 2022, which we will discuss in a moment.

Let’s start with a drilldown into the third quarter. If you take all of the double and triple counting out, the world spent $33 billion on both traditional and cloud infrastructure, and significantly for the first time, the amount of money spent on cloudy infrastructure – combining both public and private revenues – was larger than on traditional datacenter gear, at $16.8 billion and comprising 50.9 percent of total IT spending on servers, enterprise storage, and switching.

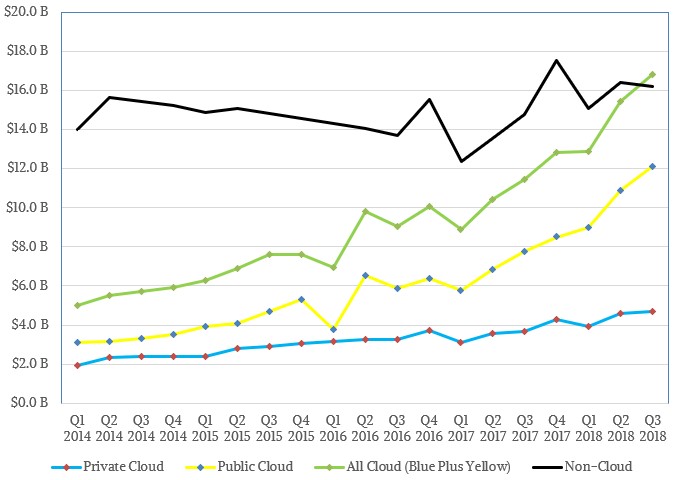

This crossover, showing the green line of cloud infrastructure above the black line of traditional infrastructure above, is a long time coming. And we mean a long time. Server virtualization, which is the key component of cloudy infrastructure, got going on IBM and clone mainframes in the late 1980s and on Unix and proprietary systems in the late 1990s, and really took off on servers running Windows Server and Linux during the Great Recession a decade later, when companies were under extreme pressure to drive up the utilization on their servers and spend less money over the long term. Given that it has been more than a decade since the Great Recession, you would think that all servers would be virtualized – and hence countable as cloudy – by now, but this is not the case. And in fact, there are plenty of workloads and customers that will prefer bare metal in the event that they have a dedicated workload running on a cluster with predictable and steady performance requirements.

As you can also see in that chart, the sales of gear to public cloud providers is on a much steeper curve and now represents a lot more revenue than sales of gear to enterprises building private clouds. The gap really opened up in 2016 and it is just getting wider with every passing year. In the third quarter of 2018, public clouds spent $12.1 billion on cloudy infrastructure, up an amazing 56.1 percent year on year, which private cloud spending was $4.7 billion, up a respectable 28.3 percent. Non-cloud core infrastructure spending rose by 14.8 percent to $16.2 billion, still significantly larger than what the public clouds and hyperscalers are spending in the aggregate. But probably not for long.

For the full 2018 year. IDC is projecting that total cloud infrastructure spending – public plus private – will grow by 37.2 percent to $65.2 billion, and non-cloud infrastructure will grow by only 14.8 percent to just under $50 billion. Spending on compute servers will rise by 59.1 percent, spending on storage will rise by 20.4 percent, and spending on Ethernet switches will rise by 18.5 percent this year, according to IDC’s crystal ball.

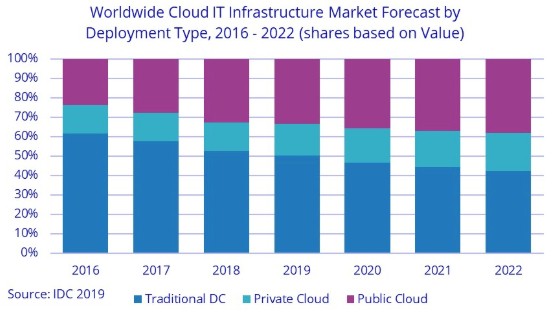

In a longer range forecast, which is shown above, IDC expects for non-cloud infrastructure to represent only 42.4 percent of core IT infrastructure spending, down from 52.6 percent last year.

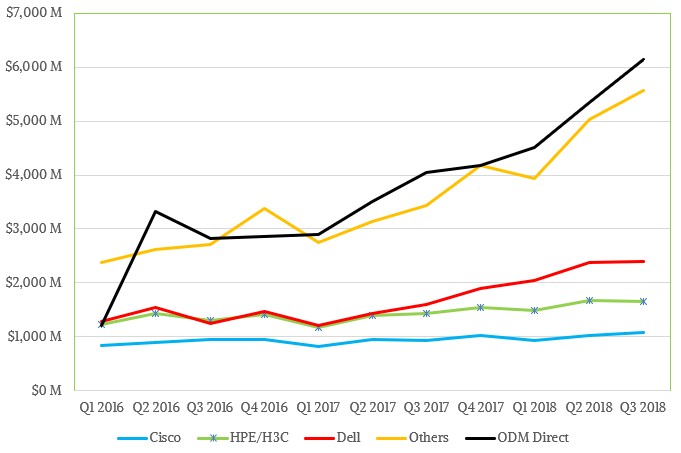

There are obviously a lot of players in the IT infrastructure supplier game, but as you might expect, Dell, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, and Cisco Systems are the big suppliers to the enterprise and some of the cloud builders and service providers; the original design manufacturers (ODMs) make custom gear for the hyperscalers and cloud builders as well as for some large enterprises and other service providers, and as a group they dominate sales. There is a healthy collection of vendors in the Others category in the chart shown below:

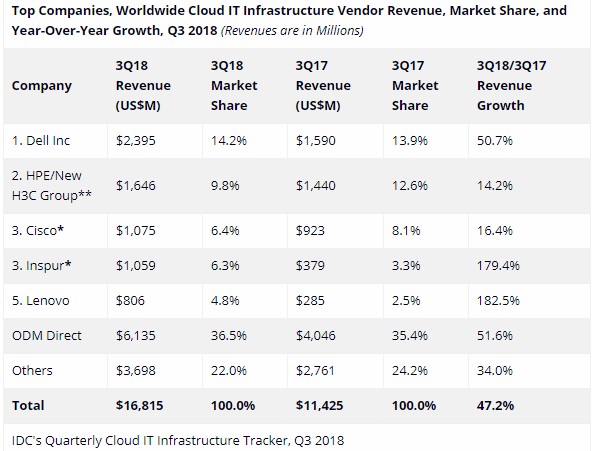

Dell has been the dominant supplier of cloud IT infrastructure for many years now, in part thanks to its long relationships with Microsoft and Tencent, two if the Super Eight hyperscalers and cloud builders. Hewlett Packard Enterprise has backed away from selling to the upper echelon, mainly because it can’t seem to make any money doing it, but it has a very large business selling cloudy gear to enterprises all over the globe. Cisco, as the world’s biggest Ethernet switch seller and an upstart in the server racket with now a decade of sales under its belt, does pretty well, too, in cloudy infrastructure, but Inspur, Huawei Technologies, and Lenovo are growing fast and nipping at its heels; Inspur actually has a hold of Cisco’s sock in the third quarter of 2018, as this table shows:

Over the past several years, Huawei sometimes sells enough cloudy infrastructure to break into the top five, but it did not this time around. Lenovo and Inspur nearly tripled their sales year-on-year, and Huawei could not keep up.

What we would love to know, and which is not discussed in the IDC report, is how much of the cloudy infrastructure is running containers compared to hypervisor-based virtualization, and how much is a hybrid of these two software sandboxing techniques. In the fullness of time, hypervisor-based server virtualization will become a kind of new mainframe – legacy, expensive, and difficult to change – in the enterprise, and new applications will be deployed in containerized platforms, as we discussed last week.

Be the first to comment