Despite the increasing competitive pressures that Intel is feeling in the datacenter and very serious issues that the company is having ramping up its 10 nanometer manufacturing processes, the datacenter business at Intel were booming in the second quarter, helping to drive a record second quarter and what is looking like will be a record full year for the chip maker.

In the quarter ended in June, Intel booked $16.96 billion in revenues, up 14.9 percent, while net income rose by 78.3 percent to just a tad bit over $5 billion. That income took a whack last year thanks to changes in the tax code brought about by the Trump administration relating to repatriating profits, so in this sense it is an easier compare. But still, considering all of this pressure, the Intel chip machine running at 14 nanometers is going strong, and in fact is the best that Intel has ever done in its history.

The huge demand for compute by hyperscalers and cloud builders has expanded the market for systems, and enterprises are investing with more vigor as well, so this is masking a lot of underlying issues that will eventually come home to roost. But for now, Intel is running a mint as much as a chip fab, and it is etching money.

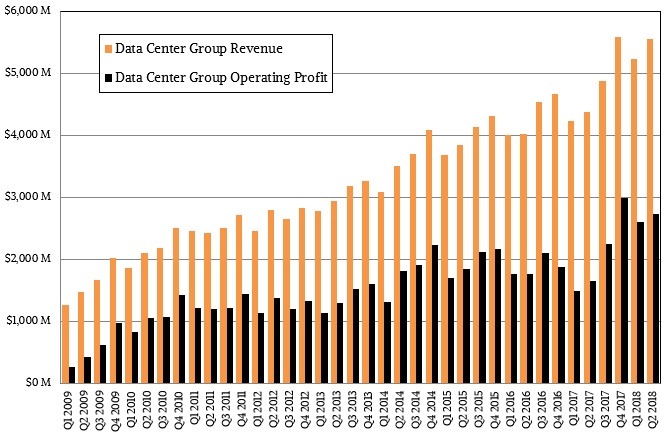

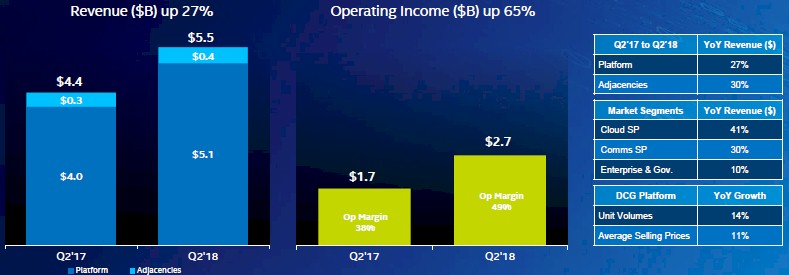

The Data Center Group, which is now headed up by Navin Shenoy, sold $5.1 billion in Xeon chips, chipsets, and motherboards in the quarter, up 26.7 percent, as well as an additional $449 million in adjacencies, up 29.8 percent, including the Omni-Path interconnect and Xeon Phi parallel processors, among other things. Across all products, unit volumes rose by 14 percent, and average selling prices rose by 11 percent, which is about as good as it gets in any business. All told, Data Center Group booked $5.55 billion in sales, up 26.9 percent, and an operating profit of $2.74 billion, up a staggering 64.8 percent. Despite our criticisms of Intel’s pricing – it is without question charging a hefty premium for its “Skylake” Xeon SP processors compared to prior generations of Xeons – clearly the company left enough bargaining room to still make plenty of dough. Companies are paying that premium. For now.

Robert Swan, Intel’s chief financial officer and interim chief executive officer after the departure last month of Brian Krzanich, who rose to the top of the company after a 35 year career at the chip maker, rolled through the numbers with the usual suspects on Wall Street, and said that the Xeon SP processors now represented nearly 50 percent of the mix of server chips sold after being a year on the market. Their “Haswell” and “Broadwell” predecessors still offer excellent value in certain cases, and are still in demand.

The revenue rise for Data Center Group was broad based across industries and geographies. Cloud service providers – what we define individually as hyperscalers and cloud builders but which Intel lumps together – saw 41 percent sales growth in the quarter, and communications service providers – telcos and such – had a 30 percent increase. These groups accounts for approximately 65 percent of Data Center Group’s revenues – a flop-flop to five years ago in 2013 when enterprises and governments accounts for 65 percent of sales. That said, even enterprises and governments saw, collectively, a 10 percent increase in the quarter, which is a good indicator of the sentiment of both about the nature of the global economy.

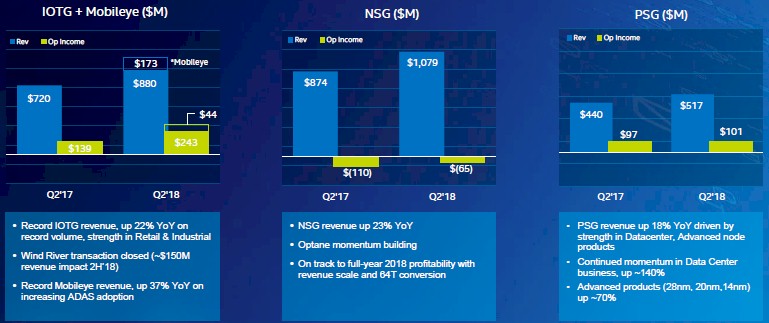

The adjacent Internet of Things Group, Non-Volatile Storage Group, and Programmable Systems Group all affected Intel’s numbers for the June quarter in different ways.

The IoT group at Intel, we would argue, definitely has a datacenter component, and clearly drives backend systems beyond that, and sales here rose by 22.2 percent to $880 million and operating income rose by 74.8 percent to $243 million. That is a big swing in midline profitability. The FPGA business had $517 million in sales, up 17.5 percent, and Swan said that the datacenter portion of Programmable Solutions Group doubled compared to this time last year; operating income was essentially flat at $101 million, however. The problematic flash and now 3D XPoint business, which Intel has invested heavily in, continues to lose money, and it posted an operating loss of 65 million against sales of $1.08 billion.

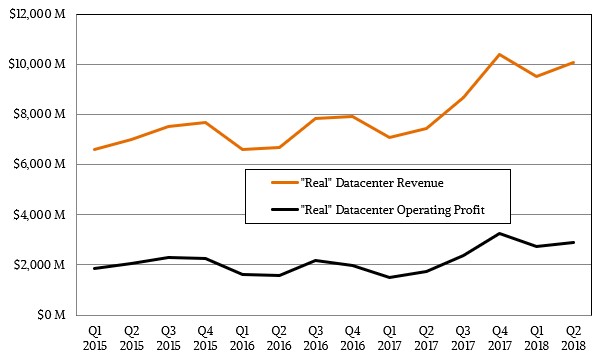

We always have some fun trying to figure out what Intel’s “real” datacenter business might look like, so we did that as usual, and here is what the trendlines look like:

In this estimate, we are literally trying to figure out the aggregate revenue and operating income of the stuff that Intel sells into the glass house. This includes half of the IoT sales and 75 percent of the non-volatile and FPGA sales. (We might be aggressive in our estimates of Intel FPGAs getting into the datacenter, but this business is relatively small and it is completely debatable if it was worth the $16.7 billion that Intel paid for Altera three years ago. It was a fair price based on the stock value, but the stock value compared to revenues and profits was way off as far as we are concerned.)

Intel has its own way of talking about this, splitting its business into data-centric and PC-centric halves. This split is approaching 50-50, according to Swan, and with the data-centric part growing 26 percent and the PC-centric part only growing 6 percent, it won’t be long before this crosses over.

Looking ahead, Intel has raised its full year guidance by $2 billion to $69.5 billion, and thinks its free cash flow for the year will be $500 million higher, hitting $15 billion against those sales. So far this year, Intel has shelled out $2.8 billion in dividends and another $5.8 billion to buy 117 million of its shares from Wall Street. Intel is expecting modest growth in its PC business, and around 20 percent growth in the data businesses for the full 2018 year. A little closer at hand, Intel thinks revenues will rise by 12 percent to $18.1 billion in the third quarter, with overall operating margins flat at 34 percent.

It remains to be seen if AMD and Cavium and IBM can capitalize on the fact that Intel is not going to be getting 10 nanometer Xeon server processors into the field until maybe the spring of 2020, as you can see from our take on the Intel Xeon roadmaps and the sunsetting of Xeon Phi. AMD can make processor sockets cheap because it is using multichip modules, and it will on its second generation of 7 nanometer products, the “Milan” chips with the “Zen 3” cores, at this time. AMD is already sampling the “Rome” kickers to the current Epyc 7000s, based on 7 nanometer processes from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp, and expects to start selling them in the first half of next year. That should be enough of a leap to make AMD some money, but with the server market expanding as it is, it may not make as big of a dent in Intel as might have looked possible a few years ago.

Be the first to comment