Way back in the early days of the commercial Internet, when we all logged into what seemed to be new but what was actually a quite old service used by academic institutions and government agencies that rode on the backbones of the telecommunications network, there were many, many thousands of Internet service providers who provided the interface between our computers and the network capacity that was the onramp of the information superhighway.

Most of these ISPs are gone today, and have been replaced by a few major telco, cable, and wireless network operators who provide us with our Internet service.

The number of companies providing Internet hosting – those operating the tens of millions of servers, usually on behalf of third parties, that actually make up the backend of the Internet rather than the network connecting the billions of end users to those backend systems – has been falling for decades, through consolidation as well as intense competition, and many of these providers of ISP and hosting services thought they could make the transition to providing public cloud capacity for compute, storage, and networking services. Some have succeeded, but it has been hard to compete and that is one reason why Verizon, a total cloud wannabe that has been investing heavily in various open source technologies to try to compete with the likes of Amazon Web Services, threw in the towel recently and “went all-in” on the AWS public cloud, following server virtualization giant VMware, which has built a variant of its SDDC stack to run on iron inside of AWS datacenters in its US West region in Oregon after spending years investing in its own datacenters.

The public cloud, like Internet service and Internet hosting, is a rich person’s game. If you can’t pony up billions of dollars for infrastructure design, manufacturing, and installation each quarter, then you probably are not going to get the kind of low infrastructure costs that AWS, Google, Microsoft, IBM, and Alibaba can, and therefore you are going to be priced out of the infrastructure cloud. If you want to offer a platform or application software service on top of these public clouds, you might be able to make some margin there, but even the platform services are being done largely by those building the largest public clouds.

Facebook does not offer public cloud services, but it may want to start doing it to hedge against pressure in its social media advertising business. Aside from this possible new entrant, we only expect consolidation among the providers of public cloud services, and in some cases, companies will just shut down their operations and cut their losses. This is not necessarily a good thing, particularly if the world shrinks down to three or four major global suppliers of public cloud capacity and maybe a handful of regional and specialist clouds.

We do not think that many companies will go all-in on one public cloud or another, and if they do, it will be many years from now after they get experience and in such a manner – very likely using containers, not virtual machines – that will allow for their applications to be more portable. The server virtualization hypervisors and their virtual machines that run operating system and application software balkanized early, with the enterprise driven by VMware’s ESXi and Microsoft’s Hyper-V and a smattering of Red Hat’s KVM (and its derivatives) and Citrix Systems XenServer (and its derivatives) and public clouds using home-supported variants of Xen or KVM. With the new containerized applications that are being developed, the substrate for virtual compute, storage, and networking is thinning than a VM on a hypervisor, and the Docker container is the format of choice. This will provide, in theory at least, a reasonable amount of portability in containerized environments between and across on-premises and public cloud infrastructure.

AWS is, of course, the touchstone for the public cloud, the thing that all others are measured against. And while AWS has had dominant share of public cloud since announcing the Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) service back in March 2006, in the past twelve quarters, its market share of the public cloud revenue has not grown even though its own revenues have been growing nicely, even if at an ever-decreasing rate that we expect from a company that is finding its natural level in a market and even if it is creating that market as it goes along. The Amazon retail business made company founder Jeff Bezos famous and feared in many markets, but AWS has made Amazon profitable in a way that none of its retail businesses ever could (which just goes to show you how high the markup on IT wares is) and has made him the richest man in the world, worth $112 billion and bypassing Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, whose net worth is now estimated at only $90 billion. (If you count the Koch Brothers, David and Charles, together, then they are the richest man in the world at $120 billion. . . .)

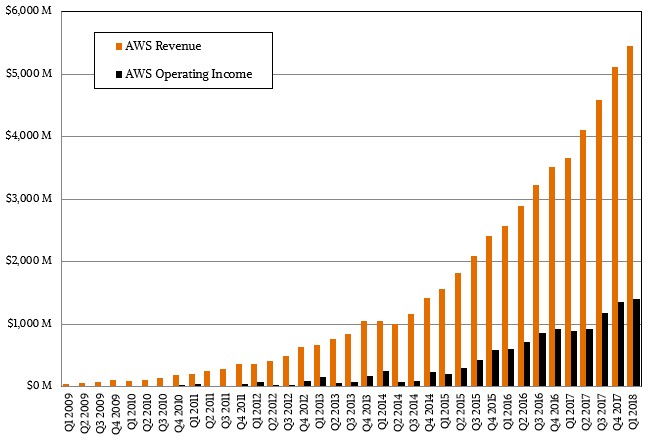

At the moment, revenue growth for AWS is rising faster than profits, and that is just a function of a lot of gears in the AWS machine changing all the time. Sometimes, the company cuts price to stimulate demand, and it takes a while for the increased demand to get revenues and therefore profits to grow again. But thus far, over the long haul, this method has worked well. Perhaps more importantly, it is AWS that gives Amazon the room – meaning the rising share price driven by rising profits and cash flow – to indulge in the conquests that Bezos will make in the future.

In the first quarter of 2018 ended in March, AWS had 48.6 percent revenue growth, to $5.44 billion, and operating income rose by 57.3 percent to $1.4 billion and represented 25.7 percent of revenues. That is not quite as good as the 40 percent to 50 percent operating income that Intel’s Data Center Group enjoys, but it is a lot better than all system makers aside from IBM with its System z mainframes gets and a far cry better than most application software companies make, too. Here’s the fun bit: Amazon overall had a tiny smidgen more than $51billion in sales, and operating profits of $1.93 billion. That’s 3.8 percent of revenue, and up 72.7 percent from the year ago period. But if you take AWS out of the picture, then the rest of Amazon only had $45.6 billion in sales and a tiny operating profit of $527 million. AWS is two thirds its profits. If you do it for the trailing twelve months, the non-AWS part of Amazon generated $173.9 billion in sales, but only $188 million – yes, that is one-tenth of a percent of revenues – as operating profit.

You can almost hear the clamoring of Wall Street for Amazon to spin out AWS, except that Wall Street has driven up Amazon stock so high – and we think unreasonably so given how meagerly profitable the online retailer has been for so long – that to do so would crash all of their portfolios. So, what you will hear on Wall Street is a lot of cars honking and a lot of quiet brokerages and investors.

It is hard not to be impressed by AWS, but let’s not get carried away. The company does not (yet) dominate corporate computing, and it has some pretty touch competition from Microsoft and Google and sometimes IBM as well as the rising threat of Alibaba. That’s what cloud watcher Synergy Research says, as you can see from its data below:

And it still does not have the kind of market share that can be called dominant and in the past three years, it has basically grown at the same pace as the public cloud market and only maintained its share. Smaller public players are being squeezed out of the market and while this has helped AWS some – Verizon and VMware are cases in point, but there are others – but seems to be helping Microsoft and Google and Alibaba more. At some point, China will wake up to the cloud and the Alibaba Cloud its fair share and maybe those platform and software services of Tencent and Baidu will get theirs, too.

Amazon’s share of about a third of worldwide cloud revenues – IaaS, PaaS, and hosted private cloud but not including SaaS – has been remarkably stable. In the first quarter, the overall market was about $15 billion, according to Synergy Research. But AWS has nothing like the monopoly status that IBM System/360 and System/370 mainframes enjoyed four decades ago in corporate computing. The customer base for corporate compute is four orders of magnitude bigger these days, too, and IT spending is probably as many orders of magnitude larger, not surprisingly. It will be hard to AWS to get a monopoly as long as other hyperscalers – particularly Microsoft and Google, and possibly Facebook if it needs to make its IT costs lower – who have public facing applications also provide cloud services to customers.

The big are going to get bigger in this market, and they are going to drive all of the smaller players out of the space. There will be niche players with specialties not addressed by the big public clouds, to be sure, perhaps with setups more amenable to HPC workloads or financial services applications, for instance, or to cover regional needs where the public clouds don’t cover well or can’t provide national data sovereignty.

This is a classic economies of scale story, and it is reasonable to assume that, in the fullness of time, a very large portion of computing will be done by service bureaus. Which is what clouds used to be called five decades ago at a time when very few companies could afford computers. We think that there will be a massive contraction in the public cloud sector, even more intense than the move from private datacenters to public clouds. It is the nature of any capital intensive business.

The funny thing about this time around is that computers will be affordable for people to buy for a long time for their own use, but the cost and hassle of managing infrastructure and the skills to do it may wane and make it more expensive to do. Because of people, not just iron. Automation of private clouds could save the day, provided vendors don’t charge too much for it and the metaphors of compute, storage, and networking are similar enough in the private cloud to the public clouds to make these skills transferrable. So far, this really hasn’t happened, but Microsoft at least under

In the very longest or runs – maybe in a decade, maybe in two – everything might be functions running on serverless architectures. We have an issue with that serverless name since servers never go away even if they are masked by many layers of software. What they should honestly be called is peopleless (meaning no one has to setup and manage them) and headless (in that they don’t show their faces). But that is a story for another day. Rest assured, the cloud builders and hyperscalers will still, way down inside, have many tens of millions of servers. All eight or ten or twelve of them, being served by maybe a few chip makers and maybe a few manufacturers. We are not looking forward to that day, because it will be a hell of a lot less fun. Hopefully, we are wrong in this prognostication. But we don’t think so. Whatever happens, we will be watching.

Morgan, Very helpful information & well explained the topic, especially the trend graphs. If this post could have added with a couple of images then it might have looked complete topic.

Once again, thank you, Morgan for sharing nice article.

Amazon Web Services (AWS) is a leading cloud computing platform that provides a wide range of services such as computing power, database storage, content delivery, and other functionalities. AWS is known for its scalability, flexibility, and cost-effectiveness, and has become a popular choice for businesses of all sizes, from startups to large enterprises.

AWS revenue has been consistently growing over the years, and in the first quarter of 2018, it reportedly had a revenue growth of 48.6 percent to $5.44 billion. Additionally, its operating income increased by 57.3 percent to $1.4 billion, which represented 25.7 percent of revenues. These growth figures are impressive and demonstrate the significant impact AWS has had on the cloud computing industry.