An unexpected jump in enterprise spending coupled with the ongoing heavy spending by hyperscalers, cloud builders, and communications companies revamping their networks of gear coupled with the ramp of the “Skylake” Xeon SP processors launched last July gave Intel the best overall quarter in its history, gauged by revenues and profits, and the best one also that its Data Center Group has ever posted.

Many are wondering if this boom can last. Intel’s top brass are not among them, but they do concede that the fourth quarter of 2017 was an unusually good one. It is hard to see if the Skylake ramp caused the spending or if the desire to spend, based on healthy fourth quarter budgets and the need to burn that money now rather than later, caused the uptake for Skylake and, we think, some enthusiasm for spending on earlier generation “Haswell” and “Broadwell” Xeon E5 processors before they disappear from the market. As we have pointed out, Intel has a lot of features in the Skylake chips – it has essentially collapsed the high-end Xeon E7 into a single E5 platform – but it is charging an E7 price premium for the E7 features that are now in what is essentially a glorified Xeon E5 line.

The difference is academic, and no less interesting because of that. The fact is, Intel has bales of cash because it still has not been hit by competitive pressure from AMD Epyc, IBM Power9, Cavium ThunderX2, Qualcomm Centriq, and quite possibly the revitalized Applied Micro X Gene processors, and the bales have been stacked higher because the pressure that might have come in 2016 or 2017 did not really hit until this year.

We think Intel will be under pressure in 2018, pressure like it has not seen in many years, and we may be witnessing peak X86 on the server platform in terms of compute in the datacenter. (The telco and comms gear is still up for grabs, and Intel is making good headway there, as it has in storage over the past decade.) We simply do not believe that any market will sustain 50 percent operating income for long when serious competition enters the field – and it doesn’t matter what that product is. Sooner or later, substitutes will be found and people will adopt them. That doesn’t mean they obliterate the other technology. IBM mainframes still drive probably on the order of $5 billion a year in hardware and operating systems, and probably drive an equal amount of additional systems software and support revenue. Cisco Systems still has dominant share in datacenter networking, despite the intense competition. So don’t misunderstand what we are saying. The Xeon processor will be the dominant platform in datacenter compute for many years to come, even if its share drops from a peak of around 90 percent of revenues and 99 percent of system shipments. We think Intel has done a brilliant job jumping off the desktop and taking over the datacenter, and we also think others have learned from its experience.

In the quarter ended in December last year, Intel’s overall sales were up 4.2 percent to $16.37 billion, and after holding down research, development, capital expense, and sales and marketing costs, the company posted just a hair over $6 billion in income before taxes. But after taking a $5.4 billion hit because of changes in deferred tax rates and to pay taxes on income parked in overseas divisions in the wake of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, plus an additional $1.3 billion for taxes due in the quarter, Intel posted a net loss of $687 million, down from a net gain of $3.56 billion in the year ago period. For the full year, Intel’s sales were $62.76 billion, up 5.7 percent, but net income was down 6.9 percent to $9.6 billion. (It is a good thing that executive pay and stock compensation is based on revenue growth, eh?) Intel exited the quarter with $3.43 billion in cash (down 38.2 percent), $1.81 billion in short term investments (down 43.8 percent), and $8.76 billion in trading assets (up 5.3 percent); this was balanced somewhat by $26.81 billion in total debt.

The revenue that Intel derives from the datacenter is, as we have pointed out before, larger than the revenues that it reports in the Data Center Group, which is where the company has the divisions that make Xeon and Xeon Phi processors, Omni-Path networking, and various chipsets and motherboards. We will look at Data Center Group as revealed and then try to ascertain the “real” Intel datacenter business.

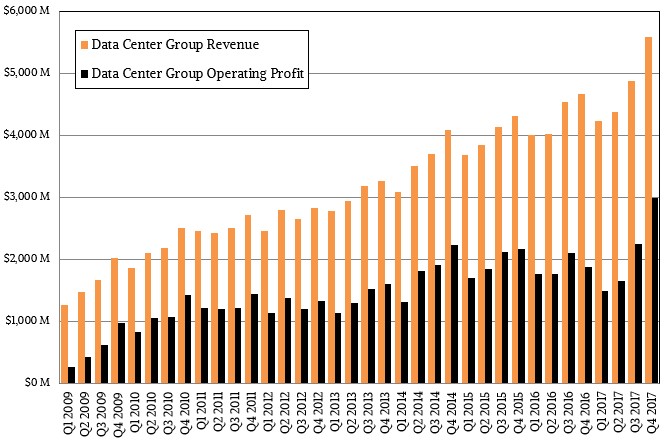

The Great Recession hit in December 2007, and in the wake of that, sales of proprietary machines as well as RISC/Itanium platforms took it on the chin, and it is not hard to see how Intel was the beneficiary of this move towards X86 iron – particularly with AMD’s Opterons not really presenting much of a competitive threat at the time in 2009 when the Great Recession was waning and the global economy started recovering. In the first quarter of 2009, when the transformational “Nehalem” Xeon 5500 series was about to be launched, Data Center Group had $1.26 billion in revenues and an operating profit of $266 million, or 21 percent of revenues. This was pretty much the bottom. In the fourth quarter of that year, Data Center Group broke through $2 billion in sales and brought 48 percent of that ($972 million) down as operating profit, kicking AMD out of the datacenter for the next eight years. Fast forward to the fourth quarter of 2017, rising through six generations of Xeons, and Data Center Group posted $5.58 billion in sales and $2.99 billion in profits. We don’t have data for server sales in the fourth quarter yet from IDC or Gartner, but suffice it to say we do not think the overall server market has grown revenues by 4.4X or profits by 11.2X over that same eight year span.

In a conference call with Wall Street analysts going over the numbers, Brian Krzanich, Intel’s chief executive officer, said that the Skylake ramp was consistent with the ramps of prior generations of Xeon processors, presumably referring to the more recent Haswell and Broadwell ramps. Intel did not provide any guidance on what share of its sales or shipments were for Skylake parts, but they have been shipping to hyperscalers and cloud builders since late 2016 and ramped through 2017 ahead of the formal July launch, so it is not like Skylake revenues were not being recognized all through last year. They were.

Intel had been guiding Wall Street to assume Data Center Group would grow in the high single digits in 2017, backing off from its statements three years back that it could grow this part of its business at 15 percent for the foreseeable future. This was, on the face of it, not possible, and we said as much because at some point the hyperscalers and cloud builders can only grow at the rate of populations and gross domestic product. Looking back from 2014, at such a growth rate, it would only take until 2022 for Data Center Group to be as large as the server market itself, which makes no sense. Unless the world is ready to spend twice as much as it does on servers – which we think it is not – then Data Center Group is more about building big clouds and smaller enterprise compute and making money on the transition, but at the end of the transition, there will be less waste and less compute sold than might otherwise have been the case.

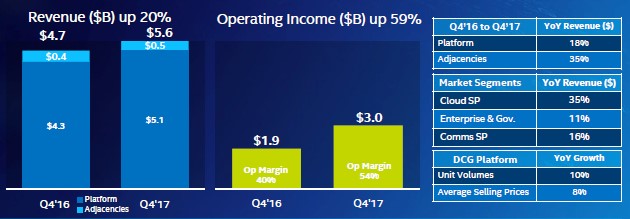

Make the money while you can, and Intel is certainly doing that. Data Center Group saw revenues rise by 19.6 percent in the fourth quarter, to $5.58 billion, and operating profit rose by 59.1 percent to $2.99 billion. Enterprise spending, which has been declining by a few points each quarter over the past several years, shot up by 11 percent in Q4 2017, surprising Intel and its partners. Sales to cloud service providers – which means hyperscalers and cloud builders in the language we use here at The Next Platform – rose by a staggering 35 percent, and even communications service providers had a 16 percent bump. The adjacencies in Data Center Group – which mean things like Omni-Path networking as well as Xeon Phi processors and custom gear – had a 34.5 percent rise, bringing in $487 million in sales. The core platform business – Xeon processors, Xeon chipsets, and Xeon motherboards – had $5.1 billion in sales, up 18.3 percent. If you add up chip and motherboard units together, unit volumes were up 10 percent in the quarter, and average selling prices rose an additional 8 percent, we think thanks to the memory and UltraPath interconnect premiums that certain Skylake processors have. (It is like having Xeon E7 features in a Xeon E5 form factor at a Xeon E6 price, if there was one. Well, there is. It is called the Xeon SP, we presume.)

The comparisons with Q4 2016 were helped because Intel had one-time warranty and intellectual property charges relating to faulty Atom processors. Thus far, there have been no charges relating to the “Spectre” and “Meltdown” speculative execution security exploits. But that could change.

Looking ahead, Intel does not expect for enterprise spending to hold up.

“Throughout the course of 2017, we guided high single-digits, and we executed to that,” explained Krzanich, referring to the overall Data Center Group revenues. “And then Q4 was not dramatically different from the first three quarters of the year with the exception of the high seasonal spend for enterprise. And that really took us from a high-single digit to low double-digit, or 11 percent growth for the year. As we go into 2018, we do not expect that. We think that in the enterprise space, things will go back down to the negative single digits range and therefore we don’t anticipate a dramatic difference in how we laid out Data Center Group a year ago.”

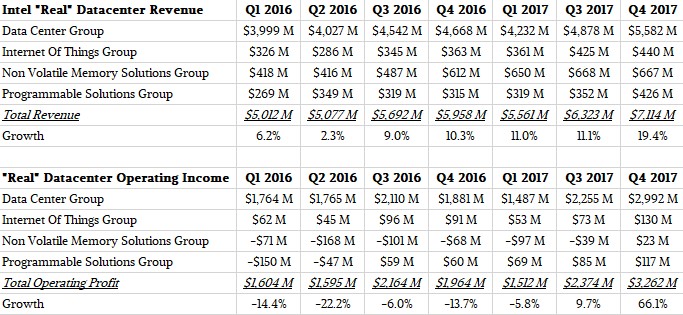

Intel’s actual datacenter business is larger than Data Center Group, and we contend that a portion of its sales of FPGAs, non-volatile storage, and other gear is really intended for and installed in datacenters, and this should be included in any assessment of Intel’s business in the glass house. We do our best to estimate this, which is shown in the table below:

We take the actual Data Center Group sales and add to it half of the IoT and 75 percent of the FPGA and non-volatile storage revenues together, and do a similar proportion of the operating incomes, to try to figure out what Intel’s “real” datacenter group revenues might look like. Here is the curve we come up with based in its 2015 financial formats, if you like charts better than tables:

It is immediately obvious why Intel does not talk about its datacenter business this way. The company has been losing money in non-volatile storage, although it did eke out an operating profit in the fourth quarter. The FPGA business is humming along and is nicely profitable, bringing 27.5 percent to the operating profit middle line. The way we do the math, Intel’s “real” datacenter business had $7.11 billion in sales in the fourth quarter (up 19.4 percent), and $3.62 billion in operating profit (up 66.1 percent), which works out to 45.9 percent of revenues.

That is another way of saying that Intel can probably reorganize its presentations to really talk about its datacenter business as distinct from its client business now, particularly if the PC business does more than decline a little and the 10 nanometer process ramp starts getting expensive.

I fail to see how you can blithely state:

“The Xeon processor will be the dominant platform in datacenter compute for many years to come, even if its share drops from a peak of around 90 percent of revenues and 99 percent of system shipments.

We think Intel has done a brilliant job jumping off the desktop (WHAT???) and taking over the datacenter,.. (WELL DOH IF ONLY THEY HAD SERVER CPUs) “

Can the boom last?

DCG Q4 revenue $5.6 B / Xeon average weighed 1K price $2834.34 sells 1,975,768 processors that is not the correct volume answer.

At 50% discount off Intel 1K $1417.17 = 3,951,536 processors sold.

At 70% discount off Intel 1K $850.30 = 6,585,893 processors sold.

At cloud commercial 82% off Intel 1K $510.18 = 10,976,489 processors sold.

Xeon Scalable Full Run Marginal Cost of Production;

At 2% of ramp volume $1984.04

At 8% of ramp volume $496.01

At 68% of ramp volume $198.30

At peak production $205.82

Full Run Average marginal cost $245.73

I will eventually calculate to state marginal cost by grades yield; XCC, HCC, LCC

In relation to AMD Epyc current list $1587.05 AWP / 3 pays foundry and provides for customer board development subsidy parity Intel = $529.02 AMD high volume commercial price.

Competitive for AMD seems just under Intel 70% discount at $793.52 where foundry gets their cost price mark up $529.02, thereafter AMD and customer split some division of the $264.51 in remaining gross revenue. Suggests Intel shipped 6.5 million plus SP units through the quarter.

In this 29th week of supply all Xeon SP open market volume is 46% of all E5/E7 v4 volume in the same supply week.

Broadwell v4 shipments relied for projecting Scalable volumes are thought on open market broker inventory data compared against known Core volumes and producing demanded up bin grades on yield sustains 87,489,137 units of production annually; begins Ivy Bridge then calculated on Intel supply signal cipher.

On XSP samples Q2 2017 and BK statement 500,000 units shipped prior to Q3 2017 XSP open market supply ramp indicates time to production volume at 17th week of supply with peak production of 21,177,939 units occurring Q4 2017 that will now be followed by three consecutive quarters of sustained volume suggesting a flat top that will essentially flat line the competition.

Historically Intel never under supplies unsure what the future holds in terms of production effectiveness and now moving below proven 14 nm geometry. XSP will be a long run.

At 87,489,137 units total production;

Platinum grades = 18,081,054 units capable of producing 2,260,132 8-way systems.

Gold grades = 44,201,141 units capable of producing up to 25,594,595 2P systems or less incorporating 4-way multiprocessing. For the standard rack of 16 data and two control plane processors = 2,455,619 racks of eight server sleds each.

W, Silver and Bronze grades = 25,206,942 uni-processor implementations.

In addition to data and transaction processing telecommunications moves to 5G and traditional network control plane Intel has longed supplied, XSP total volume including back in time v4 and v3 for embedded and non discriminating enterprise applications are meant to fulfill.

XSP may be the first Xeon run produced in excess of 100 million units.

Xeon Scalable Percent Core yields are currently;

21.25% XCC; 20C to 28C

40.86% HCC; 12C to 18C

37.42% LCC; 4C to 10C

Xeon Scalable Frequency Spread currently;

Minimum –

0.149% operate at 3.7 GHz +

17.67% operate at 3.0 to 3.6 GHz

16.30% operate at 2.5 to 2.9 GHz

53.77% operate at 2.0 to 2.4 GHz

12.08% operate at 1.7 to 1.9 GHz

All Core Turbo within minimum frequency spread;

4 GHz + = 4.03%

3.8 to 3.9 GHz = 4.89%

3.7 GHz = 48.35%

3.2 GHz = 9.55%

2.8 to 3.0 GHz = 28.82%

< 2 GHz = 4.37%

On XSP volume trajectory there will be Intel inventory, SP supply and revenue well into 2019.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing