You can’t call them the Super 8 because the discount hotel chain already has that name. But that is what they – with the they being Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook in the United States and Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and China Mobile in China – are. They are the biggest spenders, the hardest negotiators, and the most demanding customers in the IT sector.

Any component supplier that gets them buying their stuff gets kudos for their design wins and is assured, at least for a generation of products, a very steady and large demand, even if they might not bring even a penny to the bottom line. Component suppliers don’t make it up in volume, but they do make it up in the budgets of the larger number of enterprises who are not as demanding but who nonetheless spend a lot on IT infrastructure as a group and make this, however meagerly, a profitable business to participate in.

That’s the new theory, anyway. We are skeptical that most IT suppliers are making much money in the systems racket these days, but with enterprise IT spending on the decline, the vice is tightening pretty fast on profits. As we have said before, within the systems space, we think server chip maker Intel, systems software stack providers Microsoft and Red Hat, and memory makers Samsung Electronics and Micron Technology, and disk makers Western Digital and Seagate Technology probably account for the lion’s share of whatever profits come from systems and related storage. That is not to say that other companies don’t make profits, but theirs are pretty skinny, if they manage to get any at all.

That said, if you want to play the component supplier game, this is the only game in town, and AMD is extremely keen on winning some deals among the Super 8 with both its Epyc server CPUs and its Radeon Instinct GPU accelerators in the hopes that these wins will inspire confidence among the enterprise customers who still account for more than half of IT spending and who will bring AMD profits, if any can be had, from sales of those components. The ecosystem for Epyc, as we have discussed recently, is growing, which is a healthy sign.

In the past two weeks, AMD has inked two significant wins for its “Naples” Epyc 7000 series X86 server processors, which were launched in June and which represent the company’s long-awaited foray back into the server space. Last week it was Microsoft with its storage and I/O intensive instances on Azure, and this week it is Baidu with its commitment to using Epyc chips for a slew of different analytics, cloud, and AI workloads on its cloud.

These transitions in server architecture and buying habits take time, and we often don’t know about the transitions until years after they happened, or are over and forgotten. This was certainly the case with AMD’s “Hammer” family of Opteron server processors, which made their debut in April 2003 and had pretty much run out of gas by early 2008. It took a lot of cajoling and mocking by the IT punditry and analyst community for the OEMs to get on board with the Opterons, starting with IBM and Sun Microsystems and eventually moving on to Hewlett Packard and finally Dell, which held out the longest. But by then, little did we know, the ODMs were already making lots of Opteron iron for the hyperscalers, which were all younger and smaller then. Facebook and Rackspace Hosting were big and enthusiastic users of Opteron gear, and we suspect Amazon was as well but it has never said so. In early 2015, when we went to visit the Googleplex, Urs Hölzle, senior vice president of the Technical Infrastructure team at the search engine giant and on-the-rise cloud provider, did some show and tell, and two of the three home-designed motherboards he showed off from earlier in Google’s history were based on Opterons. There is a reason that AMD had 10 percent share of two-socket servers and 25 percent share of four-socket iron at the apex of the Opteron.

With the Opteron, AMD shot the gap between the 32-bit Xeon and 64-bit Itanium chips from Intel, and it did well until it had some bugs in the Opterons, the Great Recession hit, and Intel woke up and essentially cloned the Opteron with the “Nehalem” Xeon design. With the Epyc chips, AMD is trying to shoot the gap between Intel’s high pricing for “Skylake” Xeons and the competitive threat from ARM vendors Qualcomm and Cavium with their respective Centriq 2400 and ThunderX2 server chips. The Epycs have the virtue of using the same instruction set as the Intel Xeons, and they have many of the memory and I/O bandwidth benefits as well as competitive raw compute.

Microsoft made it clear earlier this year that it intended for AMD Epyc chips to be supported in its “Project Olympus” servers as well as ARM server chips from Cavium and Qualcomm and, of course, Intel’s “Skylake” Xeon SP processors. Being one of the four is better than being none of the three.

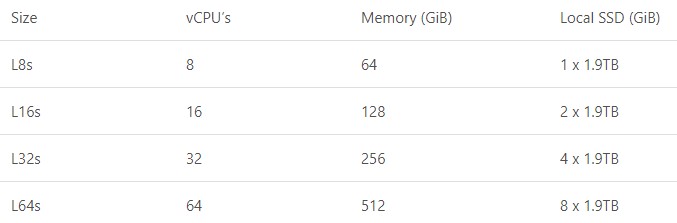

The first use of the Epyc chips by Microsoft is in the Lv2 Series virtual machines on the Azure cloud, which were announced in tech preview last week by Corey Sanders, director of compute at Microsoft’s cloud. The new L Series instances are designed for systems that need high amounts of local storage as well as high I/O throughput and are made for workloads such as Hadoop, MongoDB, Redis, and Cassandra. For the Lv2 Series instances, Microsoft is opting for a pair of 32-core Epyc 7551 processor in the Olympus node, which run at 2.2 GHz and that has a turbo speed of 3 GHz. The Lv2-Series instances look like this:

These have a lot more oomph than the “Haswell” Xeon E5 v3 processors, which ranged up to 32 cores and 6 TB of local flash storage. Microsoft could have launched a much-improved L Series instance using Skylake Xeons and added in twice as much memory and 2.5X the storage. But the point is, Microsoft did not do that, and AMD got the business instead.

At Baidu, which set up a partnership with AMD in August to use its Radeon Instinct GPUs on its cloud for machine learning and other workloads, the Epyc win is a little less precise, but could end up being as big of a deal for AMD as the Microsoft win is.

Baidu is not saying much about its Epyc plans, but what we do know is that the company is opting for a single socket deployment for its infrastructure – playing harmony to a theme that AMD has been singing all year – and that Epyc chips are available now in its datacenters. This deal is expected to ramp Epyc chips into Baidu datacenters throughout 2018.

The important thing to note here is that these are not trials. They are not tens or even hundreds of machines used in a proofs of concept, but rather they are thousands of machines that have been deployed already in 2017 at Microsoft and Baidu, and with every prospect of this growing to tens of thousands of machines more at these sites in 2018 as their initial workloads grow and more workloads come into play at these companies.

Nicely written

“these are not proof of concept deployments. They are not tens or even hundreds of machines used in a proof of concept, but thousands of machines that have been deployed already in 2017 at Microsoft and Baidu, and with every prospect of this growing to tens of thousands of machines in 2018 ”

Dramatic stuff, and as I suspected, explains the no show of retail epyc stock since its release.

For all we know, it could partly explain the vega shortage too.

I am skeptical amd are doing it for love, as you are at pains to stress Tim. The price setters are the voracious intel, and its no secret servers are the juicy segment for them.

amd with their hi yields and modular architecture, enjoy big cost advantages over intels monolithic processors. They can only win on merit as cpuS are only a small component of costs, but at a pricing scale set by intel, they can profit handsomly yet still seem cheap.

7nm EPYC with efficient tdp and ultra high core counts and IO is poised to disrupt the enterprise markets in the next few years in a huge way.

64 core EPYC is poised to double the performance of 1-2 socket servers.

Intel isn’t going to be able to bribe OEMs to keep control of the markets the way they did against Athlon and Opteron. AMD raised the bar with their CCX/infinity fabric design and Intel won’t even be able to compete against it for a few years. They are in real trouble.

AMD are the new price setters and everyone is going to benefit from real innovation breathing life into markets that have stagnated.